Breaking Ground: Natalia Palacios gets the most out of maize

It’s often joked that specialists learn more and more about less and less until they know everything about nothing, while for generalists it’s just the opposite.

In the case of Natalia Palacios, neither applies. She may have the word specialist in her title — she is a maize quality specialist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) — but throughout her career she has had to learn more and more about a growing range of topics.

As leader of the Nutrition Chapter of the Integrated Development Program and head of the Maize Quality Laboratory, Palacios’ job is to coordinate CIMMYT’s efforts to ensure that maize-based agri-food systems in low- and middle-income countries are as healthy and nutritious as possible. The scope of this work spans the breadth of maize-based agri-food systems — from seed to supper.

“What ultimately matters for human health and nutrition is the nutritional quality of the final product,” says Palacios. “High quality, nutritious grain is an important part of the puzzle, but so are the nutritional effects of various post-harvest storage, processing, and cooking techniques.”

Seeing the forest and the trees

Originally from Bogota, Colombia, Palacios studied microbiology at the Universidad de los Andes before pursuing a PhD in plant biology at the University of East Anglia and the John Innes Centre in the United Kingdom.

“I had the opportunity to work as research assistant at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Cali, Colombia,” she explains. “The exposure to interdisciplinary and international teams working for agricultural development and the leadership of my boss at that time, Joe Tohme, not only helped convince me to pursue post graduate studies in plant biology, they fostered an excitement around the real-world applications of scientific research.”

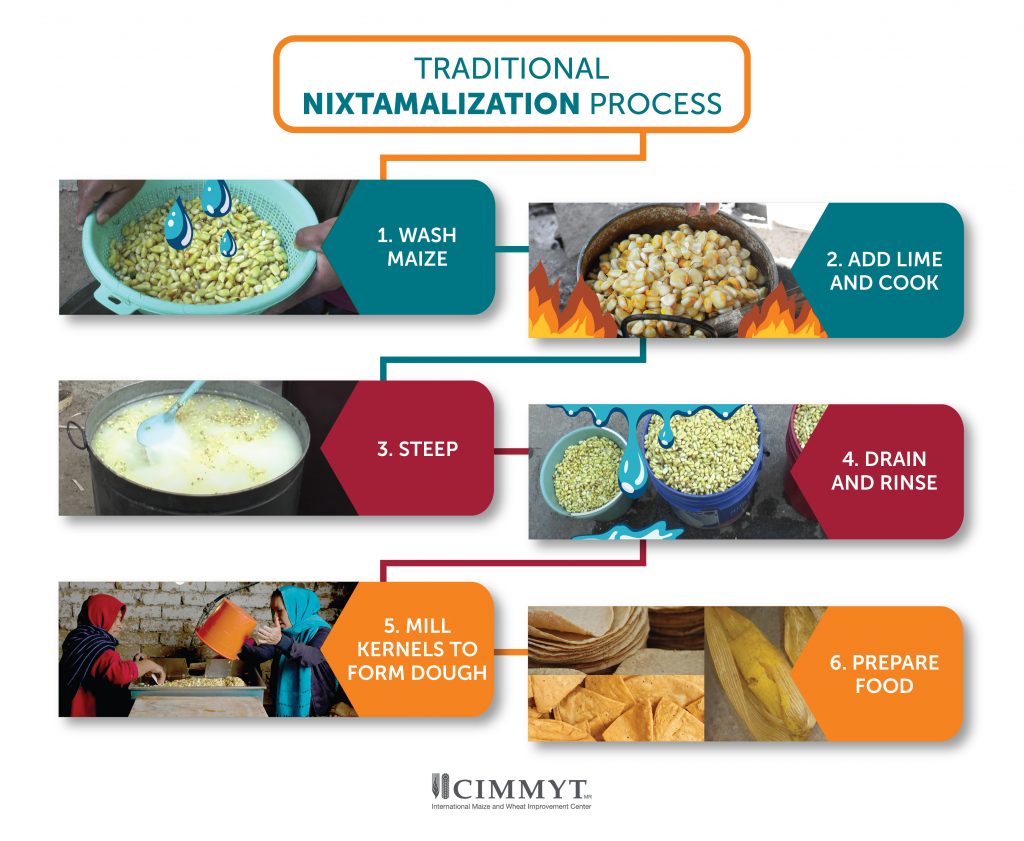

When she joined CIMMYT in 2005, Palacios worked on maize biofortification, supporting efforts to breed maize varieties rich in provitamin A and zinc. With time, she found her attention shifting towards the effect of food processing on the nutritional quality of maize-based food products, as well as to the importance of maize safety. For example, for a recent project, Palacios and her team have been analyzing the effect of a traditional thermal alkaline maize treatment known as nixtamalization on the physical composition of the grain and the nutritional quality of end products. Because of its important benefits, they are promoting this ancient technique in other geographies.

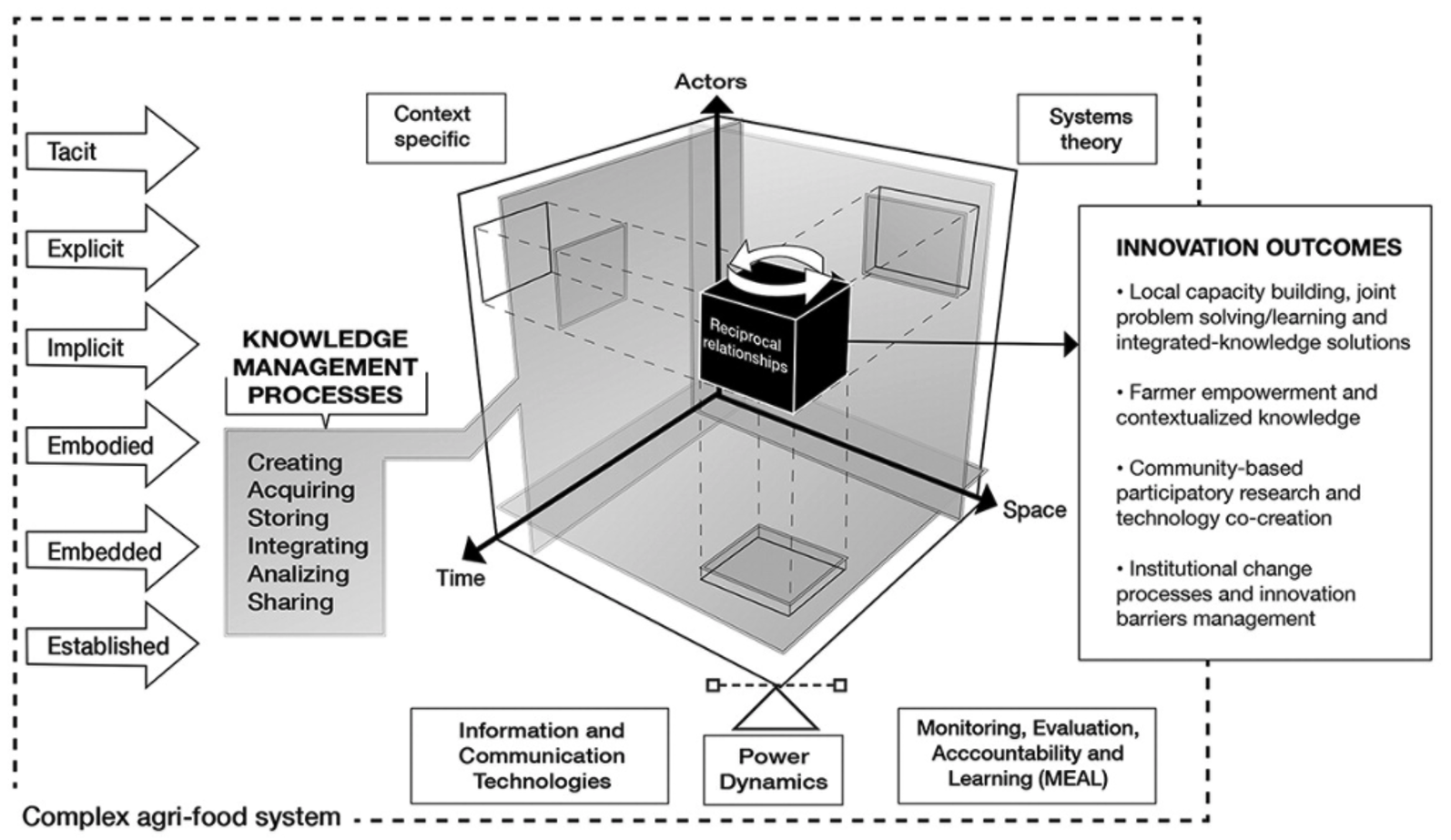

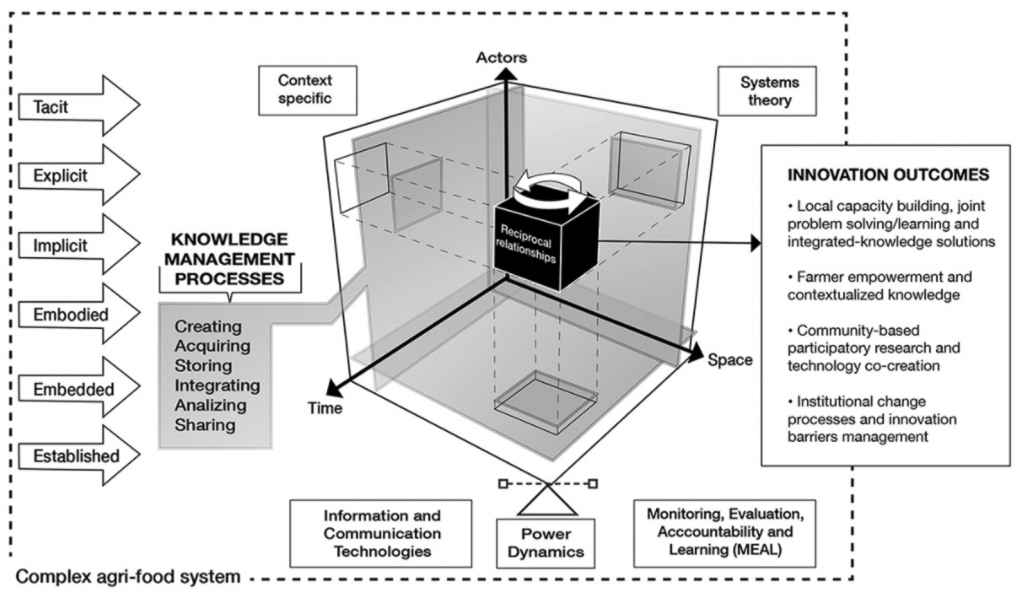

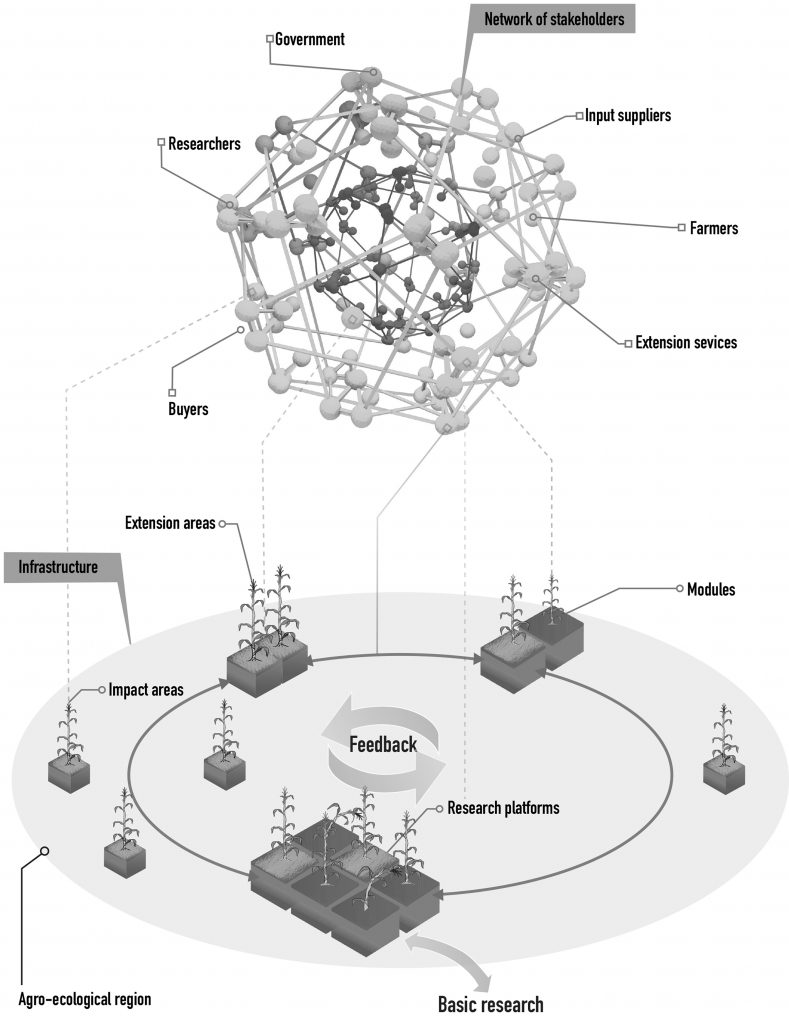

For Palacios, shifts such at this are completely in keeping with the overall goal of her work. “The main challenge we face as agricultural researchers is contributing to a nutritious, affordable diet produced within planetary boundaries,” she says. “Tackling any part of this challenge requires us to communicate between disciplines, to look at agri-food systems as a whole, and to link production and consumption.”

At the same time, for Palacios, the beauty of her work lies in going deep into a specific research question before bringing her focus back to the big picture. This movement between the specific and the general keeps her motivated, generates new questions and avenues of research, and keeps her from falling into silver-bullet thinking.

For example, her work on provitamin A biofortified maize led her to ask questions about how much of the vitamin reached consumers depending on how the grain was stored and handled. The vitamin is prone to degradation through oxidation. This led to storage and processing recommendations meant to maximize the crop’s nutritional value, including storing provitamin A maize as grain and milling it as late as possible before consumption. Researchers also worked to identify germplasm with more stable provitamin A carotenoids to be used in the breeding program.

In one study, Palacios and her coauthors found that feeding biofortified maize to hens increased the provitamin A value of their eggs, suggesting that for rural households the nutritional benefits of the improved grain could be spread out across different foodstuffs.

Bringing it all together

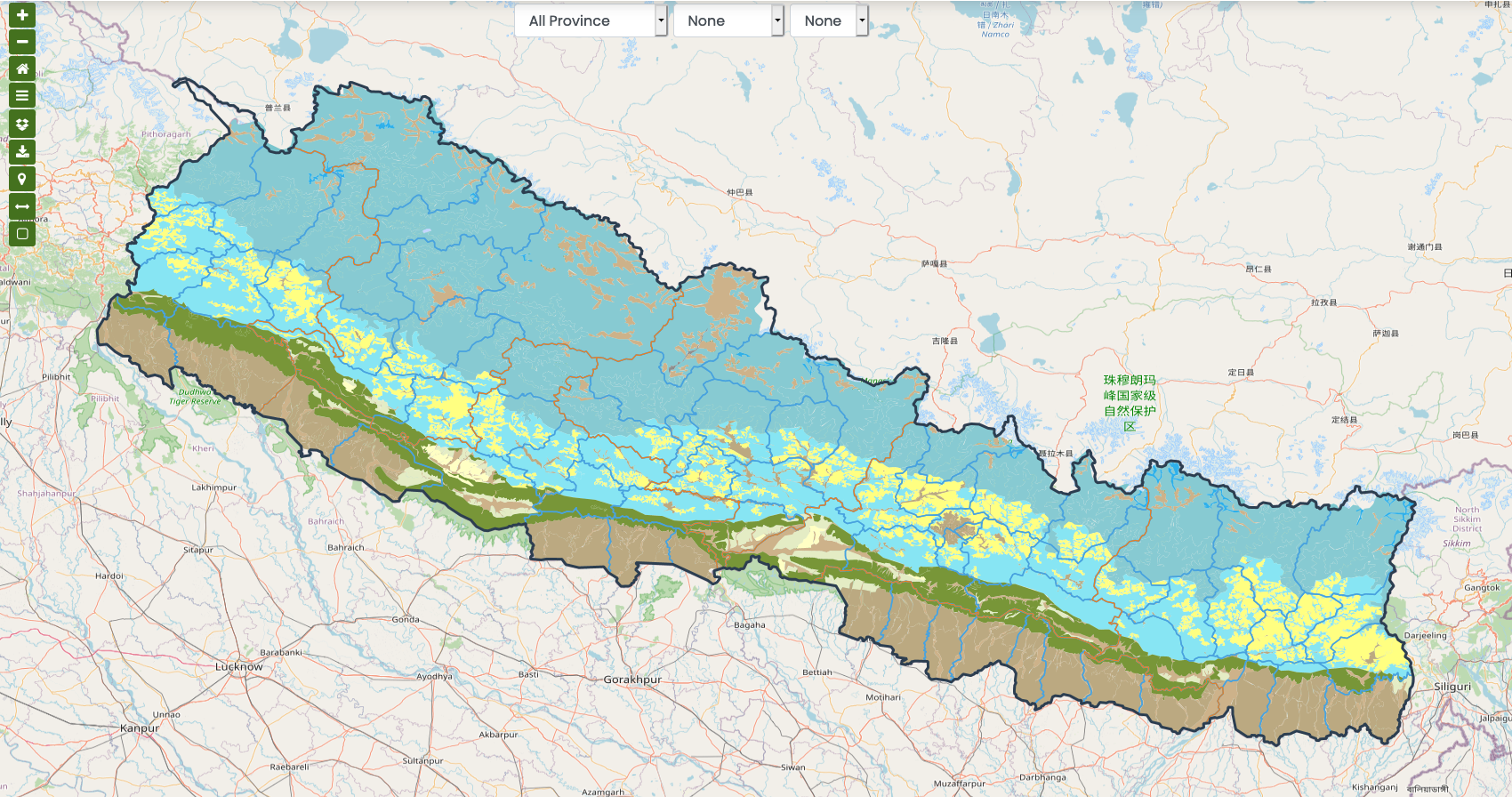

In a paper published last spring, Palacios and her co-authors bring together the insights of these various avenues of research into one comprehensive review. The point, Palacios explains “was to identify opportunities to exploit the nutritional benefits of maize — a grain largely consumed in Africa, Latin America and some parts of Asia as important part of a diet — from understanding how to leverage the its genetic diversity for the development of more nutritious varieties to mapping all the different parts of the food system where nutritional gains can be made.”

The paper encompasses sections on the biochemistry of maize, maize breeding, maize-based foodways and culture, and traditional agronomic practices like milpa intercropping. It exemplifies Palacios’ interdisciplinary approach and her commitment to exploring multiple, interconnected pathways towards more nutritious maize agri-food systems.

As CGIAR’s 2030 Research and Innovation Strategy makes clear with its emphasis on the need for a systems-level transformation of food, land and water systems, this approach is timely and much needed.

In Palacios’ words: “Food security, nutrition and food safety are inextricably linked, and we must address them from the field to the plate and in a sustainable way.”