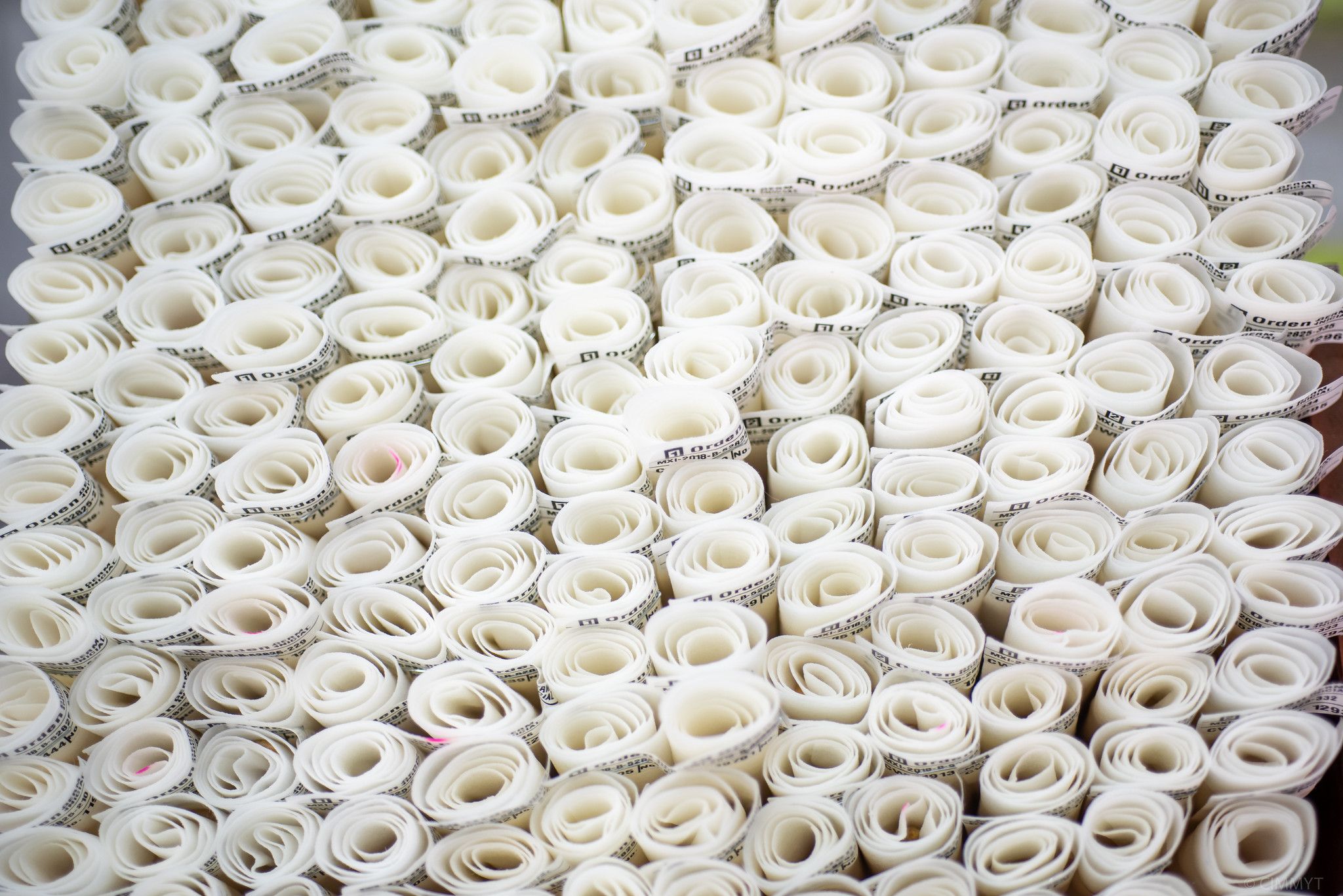

Consider the seed

The conservation of plant genetic diversity through germplasm conservation is a key component of global climate-change adaptation efforts. Germplasm banks like the maize and wheat collections at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) may hold the genetic resources needed for the climate-adaptive crops of today and tomorrow.

But how do we ensure that these important backups are themselves healthy and not potential vectors of pest and disease transmission?

This was the question that animated “Germplasm health in preventing transboundary spread of pests and pathogens,” the second webinar in Unleashing the Potential of Plant Health, a CGIAR webinar series in celebration of the UN-designated International Year of Plant Health.

“Germplasm refers to the source plants of either specific cultivars or of unique genes or traits that can be used by breeders for improved cultivars,” program moderator and head of the Health and Quarantine Unit at the International Potato Center (CIP) Jan Kreuze explained to the event’s 622 participants. “If the source plant is not healthy, whatever you multiply or use it for will be unhealthy.”

According to keynote speaker Saafa Kumari, head of the Germplasm Health Unit at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), we know of 1.3 thousand pests and pathogens that infect crops, causing approximately $530 billion in damages annually. The most damaging among these tend to be those that are introduced into new environments.

Closing the gap, strengthening the safety net

The CGIAR has an enormous leadership role to play in this area. According to Kumari, approximately 85% of international germplasm distribution is from CGIAR programs. Indeed, in the context of important gaps in the international regulation and standards for germplasm health specifically, the practices and standards of CGIAR’s Germplasm Health Units represent an important starting point.

“Germplasm health approaches are not necessarily the same as seed and plant health approaches generally,” said Ravi Khaterpal, executive secretary for the Asia-Pacific Association of Agricultural Research Institutions (APAARI). “Best practices are needed, such as CGIAR’s GreenPass.”

In addition to stronger and more coherent international coordination and regulation, more research is needed to help source countries test genetic material before it is distributed, according to Francois Petter, assistant director for the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO). Head of the CGIAR Genebank Platform Charlotte Lusty also pointed out the needed for better monitoring of accessions in storage. “We need efficient, speedy processes to ensure collections remain healthy,” she said.

Of course, any regulatory and technological strategy must remain sensitive to existing and varied social and gender relations. We must account for cultural processes linked to germplasm movement, said Vivian Polar, Gender and Innovation Senior Specialist with the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB). Germplasm moves through people, she said, adding that on the ground “women and men move material via different mechanisms.”

“The cultural practices associated with seed have to be understood in depth in order to inform policies and address gender- and culture-related barriers” to strengthening germplasm health, Polar said.

The event was co-organized by researchers at CIP and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA).

The overall webinar series is hosted by CIMMYT, CIP, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), IITA, and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). It is sponsored by the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition (A4NH), the CGIAR Gender Platform and the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB).

The third of the four webinars on plant health, which will be hosted by CIMMYT, is scheduled for March 10 and will focus on integrated pest and disease management.

Since obtaining official accreditation in 2007, CIMMYT’s Seed Health Lab (SHL) must undergo a yearly audit to detect any deviation ISO/ IEC 17025 (General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories). To fulfill this requirement, on 17-18 June 2013, the Mexican Accreditation Entity reviewed the SHL’s quality system and seed testing protocols, and also inspected its new facilities in the Bioscience Building. It applied international standards on the general requirements for testing and calibration laboratories and found zero non-conformities at the SHL.

Since obtaining official accreditation in 2007, CIMMYT’s Seed Health Lab (SHL) must undergo a yearly audit to detect any deviation ISO/ IEC 17025 (General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories). To fulfill this requirement, on 17-18 June 2013, the Mexican Accreditation Entity reviewed the SHL’s quality system and seed testing protocols, and also inspected its new facilities in the Bioscience Building. It applied international standards on the general requirements for testing and calibration laboratories and found zero non-conformities at the SHL. Seed is the lifeblood of CIMMYT’s work. Unfettered shipments, both incoming and outgoing, depend on CIMMYT and partners’ ability to keep seed clean from pathogens and to properly document seed health. To promote protocol consistency among Mexican seed technicians, a weeklong seed-health workshop was held during 29 November-03 December 2010 at CIMMYT-El Batán.

Seed is the lifeblood of CIMMYT’s work. Unfettered shipments, both incoming and outgoing, depend on CIMMYT and partners’ ability to keep seed clean from pathogens and to properly document seed health. To promote protocol consistency among Mexican seed technicians, a weeklong seed-health workshop was held during 29 November-03 December 2010 at CIMMYT-El Batán. On Tuesday, 30 November, the participants took a break from the lab to enjoy the fresh air of the Tlaltizapán station where they learned field inspection and sample collection procedures. The course focused on diseases prevalent in Mexico and included presentations from Monica Mezzalama as well as two guest lecturers, Ana María Hernández, plant pathologist, and Gustavo Mora, plant disease epidemiologist, both professors from the Colegio de Postgraduados, Texcoco, Mexico. The workshop was the first of its kind, and due to resounding positive feedback, it is hoped to be continued annually. Thanks to all that made the course possible, a special thanks to Noemí Valencia, seed health laboratory supervisor; Gabriela Juárez, research assistant; Laura Rodríguez, training office assistant; and Óscar Bañuelos, Tlatizapán station superintendent.

On Tuesday, 30 November, the participants took a break from the lab to enjoy the fresh air of the Tlaltizapán station where they learned field inspection and sample collection procedures. The course focused on diseases prevalent in Mexico and included presentations from Monica Mezzalama as well as two guest lecturers, Ana María Hernández, plant pathologist, and Gustavo Mora, plant disease epidemiologist, both professors from the Colegio de Postgraduados, Texcoco, Mexico. The workshop was the first of its kind, and due to resounding positive feedback, it is hoped to be continued annually. Thanks to all that made the course possible, a special thanks to Noemí Valencia, seed health laboratory supervisor; Gabriela Juárez, research assistant; Laura Rodríguez, training office assistant; and Óscar Bañuelos, Tlatizapán station superintendent.