June, 2005

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

Outside a straw and mud-walled house in rural Hidalgo, Mexico, with chickens walking around and the smell of the cooking fire wafting through the air, CIMMYT researcher Dagoberto Flores drew lines with a stick in the red earth as he explained to a farmer’s wife how maize seed should be planted for an experiment. Along with CIMMYT researcher Alejandro Ramírez, Flores was distributing improved seed in communities where they had conducted surveys for a study on gene flow.

The movement of genes between populations, or gene flow, happens when individuals from different populations cross with each other. CIMMYT social scientist Mauricio Bellon is leading a study that aims to find out the impact of farmers’ practices on gene flow and on the genetic structure of landraces. It will document how practices differ across farming systems, analyze their determinants, figure out how much farmers control gene flow, and explore gene flow’s impacts on maize fitness and diversity and on farmers’ livelihoods.

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The team made it a priority to give the farmers what they requested for free. They drove around in a pick-up truck with seed they had acquired from CIMMYT scientists. They brought black, white, and yellow varieties that were native to the area and had been improved with weevil and drought resistance, and they also brought three CIMMYT varieties that were well adapted to a similar environment in Morelos, Mexico. They explained to the farmers how each variety should be planted in separate squares to facilitate pure seed selection.

“It’s a way to thank them, to bring something back to the communities,” says Bellon. Bringing improved germplasm for experimentation to interested small-scale farmers also allows researchers to get feedback in a more systematic way. The farmers will produce the maize independently, and they can save or discard seed from whichever varieties they choose. The team also distributed seed to farmers in Veracruz, and they plan to return after flowering and at harvest time to see how the improved seed fares compared with native varieties. That component of the project could be the beginning of further research in collaboration with farmers.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Many people grew coffee around Huatzalingo until about 10 years ago when the price plummeted. A kilogram of coffee used to fetch a price of about 20 pesos, or US$ 2. Now it fetches about five pesos, or 50 cents, per kilo, and even less during harvest time when the crop is abundant. Coffee producers in the area receive average government subsidies of between 125 and 300 pesos, or between US$ 10-30. One effect of the price drop has been increased immigration to Mexico City, to the city of Reynosa near the US border, and to lowland areas where orange cultivation is booming.

Partly in response to the crisis, farmers have started diversifying into alternative crops such as vanilla, citrus fruits, bananas, sugar cane, sesame, beans, chayote, chili peppers, and lentils, but the poor soils do not favor more lucrative crops. Maize is still the most important agricultural product in people’s diets in this area, and farmers grow it primarily for family consumption. They exchange seed with friends, neighbors, and producers in nearby communities, and they have conserved diverse native varieties.

In Mexico, maize has such great genetic diversity because farmers’ practices encourage the further evolution of maize landraces. Maize was domesticated about 6,000 years ago within the current borders of Mexico. Farmers created a variety of races to fit different needs by mixing different maize types, and they still experiment like that to this day. They save seed between seasons and trade seed with each other, and the wind carries pollen between different cultivars to create new mixtures.

“They are not artifacts in a museum,” Bellon says about landraces. “They are changing, they are moving.” Seed selection has a great impact on gene flow. Poor farmers typically exchange seed with each other, but little has been documented about the social relations that drive seed systems. With growing concerns about a loss of crop genetic diversity and a need to conserve genetic resources in recent years, it is important to understand the social principles of seed flow (and ultimately gene flow) in Mexico. The study findings will assist in exploration of the potential impact of transgenes. The researchers will develop models to try to predict how a transgene would diffuse and behave after it has been in a population for 10 or 20 years.

By learning about the relationships between farmers’ practices and gene flow, researchers hope to promote more effective policies regarding the conservation of diversity in farmers’ fields, the distribution of improved germplasm, and transgene management. Funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the study combines social science with genetics to connect social and biological factors in maize varieties. Molecular markers will help show how much gene flow has occurred over time between the Mexican highlands and lowlands.

Researchers used geographic information systems to choose varied environments for the survey. Starting in October 2003, they sampled maize populations and interviewed the male and female heads of 20 households in each community for a total of 800 intensive interviews in 400 households. They asked about topics such as principal crops, planting cycles and methods, maize varieties, machinery and tools, infrastructure, language, seed selection, fertilizer, pest and weed control, plant height, harvest, transportation, production problems, maize uses, the sale and demand of different varieties, knowledge about maize reproduction, husk commercialization, and level of migration.

Preliminary findings have already surprised Bellon. A growing market for maize husks, which are used to wrap traditional foods such as tamales, is changing the economics of maize production. Owing to increasing demand from the US, husks have become more commercially important and profitable than grain in some communities. Facing abysmally low grain prices, the success of husk production has caused some producers to seek maize varieties with high quality husks, almost regardless of grain quality.

Bellon was also surprised at the lack of improved varieties in the areas they studied. Farmers tended to seek out and plant native varieties instead of hybrids. Some farmers thought hybrids were expensive, produced poor quality husks, and required good land, chemicals, and fertilizer, but they thought native varieties adapted easily to marginal local conditions.

The study grew out of a six-year project in Oaxaca that examined the relationship between farmers’ practices and the genetic structure of maize landraces and seed flow among farmers. It also explored the implications of transgenic technologies. However, while the Oaxaca project examined a few communities located in one environment, the idea with this follow-up study was to examine many locations in the same and different environments. In that way researchers can find out if gene flow is localized or if it crosses between regional environments. “It’s the same research model on a broader scale,” says Bellon.

For information: Mauricio Bellon

Young Indonesian researchers are reaping the benefits of collaboration with CIMMYT and at the same time helping farmers in their country.

Young Indonesian researchers are reaping the benefits of collaboration with CIMMYT and at the same time helping farmers in their country. “This is the untold story of the quiet biotech revolution going on in maize breeding in Asia,” says CIMMYT’s Luz George. “It is a successful transfer of technology from CIMMYT to developing countries which has now found direct application in the work of national program maize breeders.”

“This is the untold story of the quiet biotech revolution going on in maize breeding in Asia,” says CIMMYT’s Luz George. “It is a successful transfer of technology from CIMMYT to developing countries which has now found direct application in the work of national program maize breeders.” New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance. What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity.

What role do farmers play in the evolution of maize diversity? How extensive are the farming networks and other social systems that influence gene flow? These and other questions are helping researchers to combine knowledge of the genetic behavior of plants with information on human behavior to understand the many factors that affect maize diversity. The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed?

The farmers visited by Flores and Ramírez in early June near Huatzalingo and Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo are from just 2 of 20 study communities spanning ecologies from Mexico’s highlands down to the lowlands. Six months earlier, when farmers in these communities responded to researchers’ survey question, they asked some questions of their own: What does CIMMYT do? How can we get seed? Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs.

Farmers in the survey area of rural Hidalgo grow maize on the poorest, most steeply sloping land and struggle with soil diseases, low soil fertility, leaf diseases, low grain prices, and limited information about the use of chemical herbicides. Strong wind, rain, and hurricanes damage crops. Landslides cause erosion. Some farmers have access to roads and can transport their harvest by vehicle, but some farms located far from the communities have no highway access. The paths to farmers’ fields can be so narrow that not even cargo animals can maneuver on them with loads, so farmers must carry the harvest on their backs. Some walk 10 kilometers up and down slopes with heavy bags on their backs. A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly.

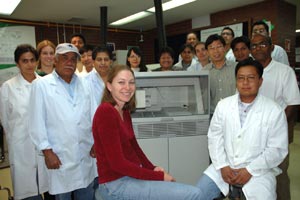

A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly. The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.”

The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.” The Seed Health Laboratory, part of CIMMYT’s Seed Inspection and Distribution Unit (SIDU) has become the first in the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) to gain International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification

The Seed Health Laboratory, part of CIMMYT’s Seed Inspection and Distribution Unit (SIDU) has become the first in the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) to gain International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification

All of us who work at CIMMYT have noticed its recent growth—new faces, new projects, and new facilities being constructed at El Batán and elsewhere. All of this means more research is getting done, and, inparticular, the global maize program is using and producing more breeding materials.

All of us who work at CIMMYT have noticed its recent growth—new faces, new projects, and new facilities being constructed at El Batán and elsewhere. All of this means more research is getting done, and, inparticular, the global maize program is using and producing more breeding materials.

During the visit, Govaerts demonstrated the MasAgro machinery platform, and explained the importance of Mexico being able to manufacture crop machinery and implements that can be used in the different agro-ecological zones of the country. Govaerts stressed that these technology transfer processes must impact farmers, technicians, researchers, and companies which develop this type of machinery in the different regions.

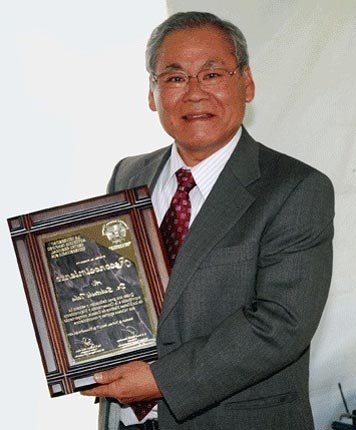

During the visit, Govaerts demonstrated the MasAgro machinery platform, and explained the importance of Mexico being able to manufacture crop machinery and implements that can be used in the different agro-ecological zones of the country. Govaerts stressed that these technology transfer processes must impact farmers, technicians, researchers, and companies which develop this type of machinery in the different regions. At El Batán on 20 December 2011, CIMMYT staff, family, and friends joined specialists from Mexican universities and national research programs, Second Secretary Shin Taniguchi of the Japanese Embassy in Mexico, and farmers in a gala farewell luncheon for the retiring head of maize genetic resources, Suketoshi Taba, after an illustrious 36-year career at CIMMYT in the study, conservation, and use of maize diversity.

At El Batán on 20 December 2011, CIMMYT staff, family, and friends joined specialists from Mexican universities and national research programs, Second Secretary Shin Taniguchi of the Japanese Embassy in Mexico, and farmers in a gala farewell luncheon for the retiring head of maize genetic resources, Suketoshi Taba, after an illustrious 36-year career at CIMMYT in the study, conservation, and use of maize diversity.