Faster results at a lower cost

The current COVID-19 pandemic — and associated measures to reduce its spread — is projected to increase extreme poverty by 20%, with the largest increase in sub-Saharan Africa, where 80 million more people would join the ranks of the extreme poor. Accelerating the process of delivering high-quality, climate resilient and nutritionally enriched maize seed is now more critical than ever.However, developing these varieties is not a rapid or cheap process. Over the course of five years, researchers on the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) project developed a range of tools and technologies to reduce the overall cost of producing a new high yielding, stress tolerant hybrids for smallholder farmers in the region.

Maize breeding starts with crossing two parents and essentially ends after testing their great-great-great-great grandchildren in as many locations as possible. This allows plant breeders to identify the new varieties which will perform well in the conditions faced by their target beneficiaries — in the case of STMA, smallholder farmers in Africa. In other parts of the world, new tools and technologies are routinely added to breeding programs to help reduce the cost and time it takes to produce new varieties.

Scientists on the STMA project focused on testing and scaling new tools specifically for maize breeding programs in sub-Saharan Africa and began by taking a closer look at the most expensive part of the breeding process: phenotyping or collecting precise information on plant traits.

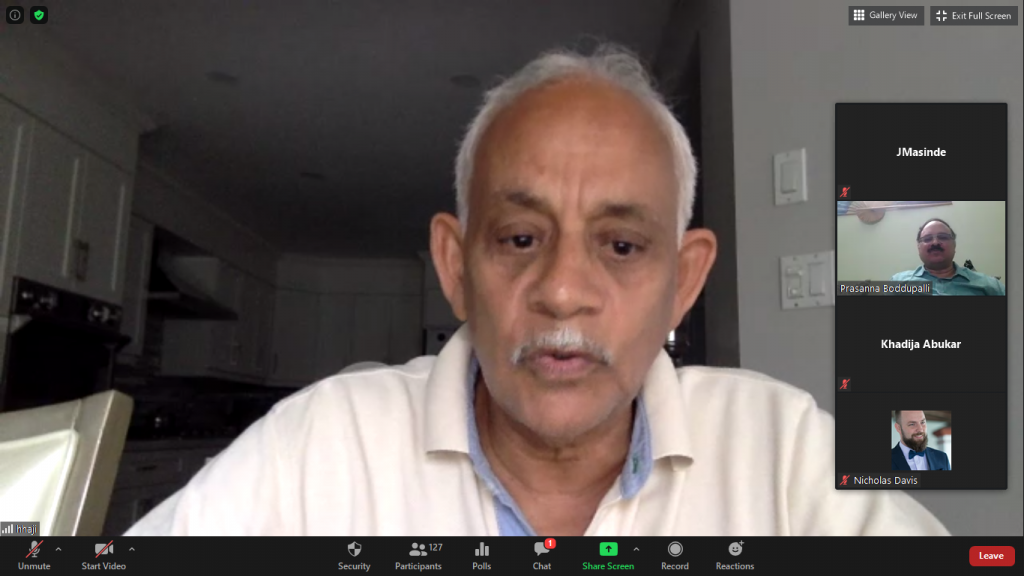

“Within a breeding program, phenotyping is the single most costly step,” explains CIMMYT molecular breeder Manje Gowda. “Molecular technologies provide opportunities to reduce this cost.” The research team tested two methods to speed up this step and make it more cost efficient: forward breeding and genomic selection.

Speeding up a long and costly process

Two important traits maize breeders look for in their plant progeny are susceptibility for two key maize diseases: maize streak virus (MSV) and maize lethal necrosis (MLN). In traditional breeding, breeders must extensively test lines in the field for their susceptibility to these diseases, and then remove them before the next round of crossing. This carries a significant cost.

Using a process called forward breeding, scientists can screen for DNA markers known to be associated with susceptibility to these diseases. This allows breeders to identify lines vulnerable to these diseases and remove them before field testing.

Scientists on the STMA project applied this approach in CIMMYT breeding programs in eastern and southern Africa over the past four years, saving an estimated $300,000 in field costs. Under the AGG project, research will now focus on applying forward breeding to identify susceptibility for another fast-spreading maize pest, fall armyworm, as well as extending use of this method in partners’ breeding programs.

Forward breeding is ideal for “simple” traits which are controlled by a few genes. However, other desired traits, such as tolerance to drought and low nitrogen stress, are genetically complex. Many genes control these traits, with each gene only contributing a little towards overall stress tolerance.

In this case, a technology called genomic selection can be of service. Genomic selection estimates the performance, or breeding value, of a line based largely on genetic information. Genomic selection uses more than 5,000 DNA markers, without the need for precise information about what traits these markers control. The method is ideal for complicated traits such as drought and low nitrogen stress tolerance, where hundreds of small effect genes together largely control how a plant grows under these stresses.

CIMMYT scientists used this technology to select and advance lines for drought tolerance. They then tested these lines and compared their performance in the field to lines selected conventionally. They found that the two sets of resulting hybrid varieties — those advanced using genomic selection and those advanced in the field — showed the same grain yield under drought stress. However, genomic selection only required phenotyping half the lines, achieving the same outcome with half the budget.

Innovations in the field

While DNA technology is reducing the need for extensive field phenotyping, research is also underway to reduce the cost of the remaining necessary phenotyping in the field.

Typically, many traits — such as plant height or leaf drying under drought stress — are measured by hand, using the labor of large teams of people. For example, plant and ear height is traditionally measured by a team of two using a meter stick.

Mainasarra Zaman-Allah, a CIMMYT abiotic stress phenotyping specialist based in Zimbabwe, has been developing faster, more accurate ways to measure these traits. He implemented the use of a small laser sensor to measure plant and ear height which only requires one person. This simple yet cost effective tool has reduced the cost of measuring these traits by almost 60%. Similarly, using a UAV-based platform has reduced the cost of measuring a trait known as canopy senescence — leaf drying associated with drought susceptibility —by over 65%.

The identification of plants which are tolerant to key diseases has traditionally involved scoring the severity of disease in each plot visually, but walking through hundreds of plots daily can lead to errors in human judgement. To combat this, CIMMYT biotic stress phenotyping specialist LM Suresh collaborated with Jose Luis Araus and Shawn Kefauver, scientists at the University of Barcelona, Spain, to develop image analysis software that can quantify disease severity, thereby avoiding problems associated with unintentional human bias.

Plant breeders need uniform, or homozygous, lines for selection. With conventional plant breeding this is difficult: no matter how many times you cross a line, a small amount of DNA will remain heterozygous — having two different alleles of a particular gene — and reduce accuracy in line selection.

A technology called doubled haploid allows breeders to develop homozygous lines within two seasons. While this technology has been used in temperate maize breeding programs since the 1990s, it was not available for tropical environments until 10 years ago. In 2013, thanks to joint work with Kenyan partners at the CIMMYT Doubled Haploid facility in Kiboko, this technology was made available to African breeding programs. Now Vijay Chaikam, a CIMMYT doubled haploid specialist based in Kenya, is working towards reducing the cost of this technology as well.

The efforts begun by the STMA research team is now continuing under the Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods (AGG) project. As this work is carried forward, the next crucial step is ensuring that the next generation of African maize breeders have access to these technologies and tools.

“Improving national breeding programs will really drive success in raising maize yields in the stress prone environments faced by many farmers in our target countries,” says Mike Olsen, CIMMYT’s upstream trait pipeline coordinator. Under AGG, in collaboration with the CGIAR Excellence in Breeding Program, these tools will be scaled out.