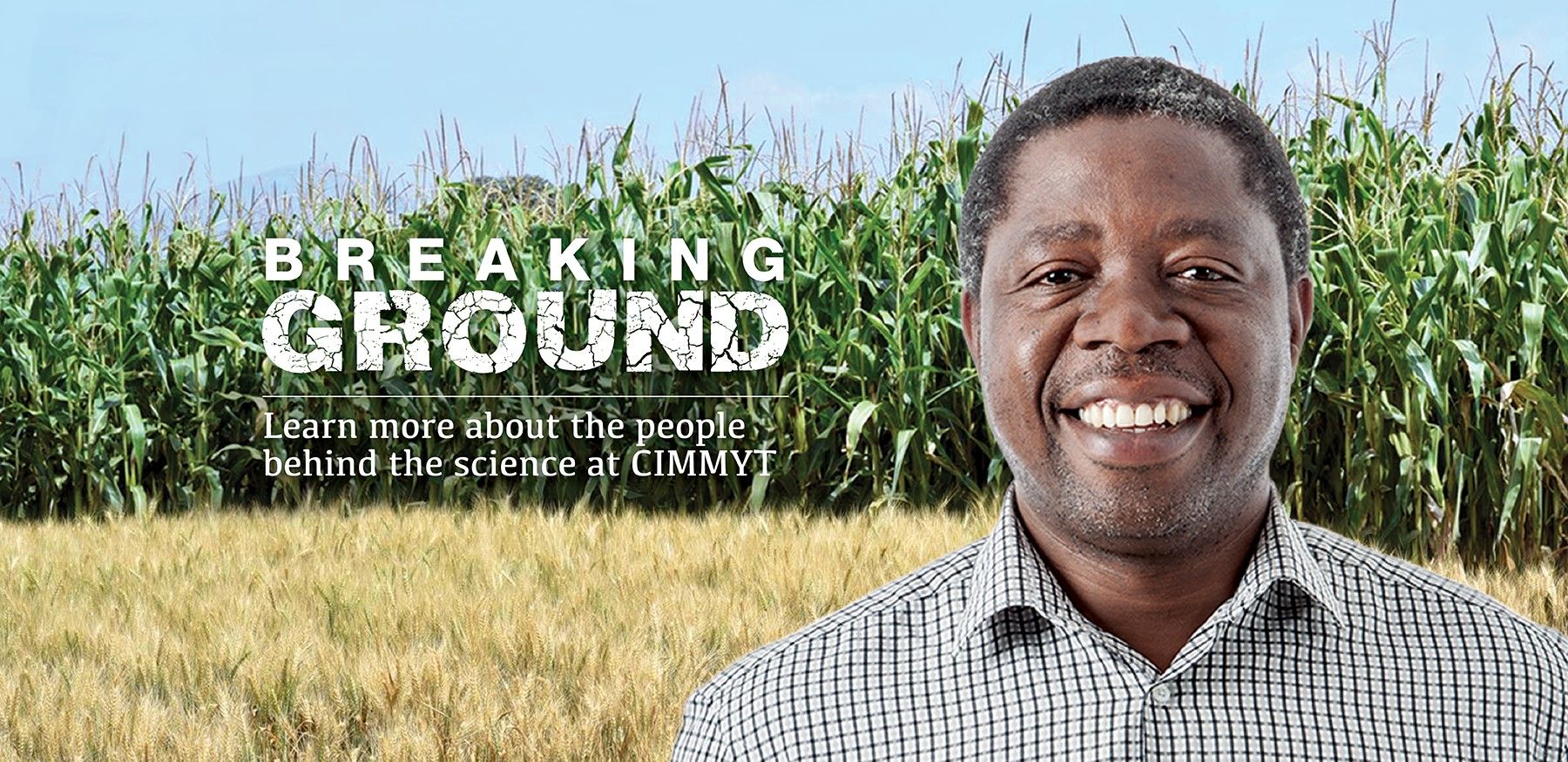

Breaking Ground: Isaiah Nyagumbo advances climate-smart technologies to improve smallholder farming systems

Most small farmers in sub-Saharan Africa rely on rain-fed agriculture to sufficiently feed their families. However, they are increasingly confronted with climate-induced challenges which hinder crop production and yields.

In recent years, evidence of variable rainfall patterns, higher temperatures, depleted soil quality and infestations of destructive pests like fall armyworm cause imbalances in the wider ecosystem and present a bleak outlook for farmers.

Addressing these diverse challenges requires a unique skill set that is found in the role of systems agronomist.

Isaiah Nyagumbo joined the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in 2010 as a Cropping Systems Agronomist. Working with the Sustainable Intensification program, Nyagumbo has committed his efforts to developing conservation agriculture technologies for small farming systems.

“A unique characteristic of systems agronomists,” Nyagumbo explains, “is the need to holistically understand and address the diverse challenges faced by farming households, and their agro-ecological and socio-economic environment. They need to have a decent understanding of the facets that make technology development happen on the ground.”

“This understanding, combined with technical and agronomical skills, allows systems agronomists to innovate around increasing productivity, profitability and efficient farming practices, and to strengthen farmers’ capacity to adapt to evolving challenges, in particular those related to climate change and variability,” Nyagumbo says.

Gaining expert knowledge

Raised by parents who doubled as teachers and small-scale commercial farmers, Nyagumbo was exposed to the realities of producing crops for food and income while assisting with farming activities at his rural home in Dowa, Rusape, northeastern Zimbabwe. This experience shaped his decision to study for a bachelor’s degree in agriculture specializing in soil science at the University of Zimbabwe and later a master’s degree in soil and water engineering at Silsoe College, Cranfield University, United Kingdom.

Between 1989 and 1994, Nyagumbo worked with public and private sector companies in Zimbabwe researching how to develop conservation tillage systems in the smallholder farming sector, which at the time focused on reducing soil erosion-induced land degradation.

Through participatory technology development and learning, Nyagumbo developed a passion for closely interacting with smallholder farmers from Zimbabwe’s communal areas as it dawned to him that top-down technology transfer approaches had their limits when it comes to scaling technologies. He proceeded to study for his PhD in 1995, focusing on water conservation and groundwater recharge under different tillage technologies.

Upon completion of his PhD, Nyagumbo started lecturing at the University of Zimbabwe in 2001, at the Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Engineering, a route that opened collaborative opportunities with key international partners including CIMMYT.

“This is how I began my engagements with CIMMYT, as a collaborator and jointly implementing on-farm trials on conservation agriculture and later broadening the scope towards climate-smart agriculture technologies,” Nyagumbo recalls.

By the time an opportunity arose to join CIMMYT in 2010, Nyagumbo realized that “it was the right organization for me, moving forward the agenda of sustainability and focusing on improving productivity of smallholder farmers.”

Climate-smart results

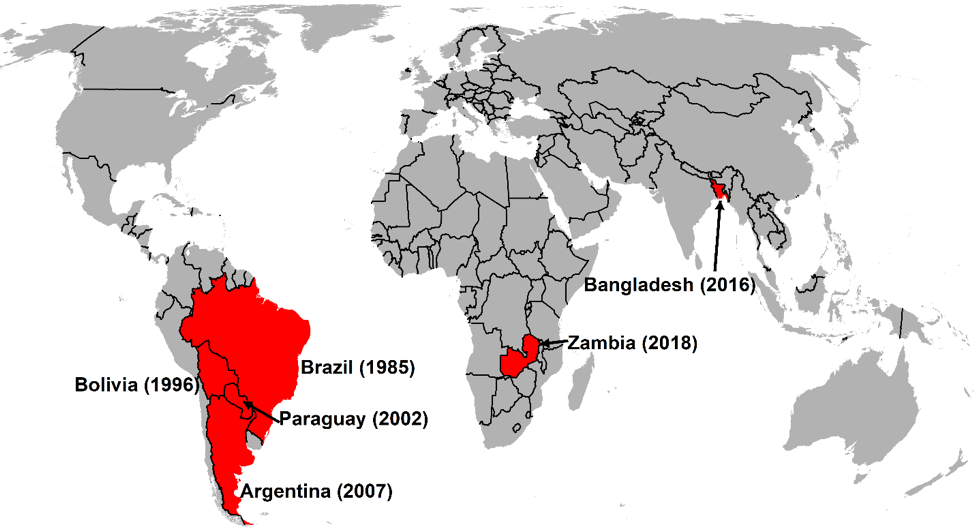

Projects such as SIMLESA show results of intensification practices and climate-smart technologies aimed at improving smallholder farming systems in eastern and southern Africa.

“One study showed that when conservation agriculture principles such as minimum tillage, rotation, mulching and intercropping are applied, yield increases ranging from 30-50 percent can be achieved,” Nyagumbo says.

Another recent publication demonstrated that the maize yield superiority of conservation agriculture systems was highest under low-rainfall conditions while high-rainfall conditions depressed these yield advantages.

Furthermore, studies spanning across eastern and southern Africa also showed how drainage characteristics of soils affect the performance of conservation agriculture technologies. “If we have soils that are poorly drained, the yield difference between conventional farming practices and conservation agriculture tends to be depressed, but if the soils are well drained, higher margins of the performance of conservation agriculture are witnessed,” he says.

Currently, Nyagumbo’s research efforts in various countries in eastern and southern Africa seek to better understand the resilience benefits of cereal-legume cropping systems and how different planting configurations can help to improve system productivity.

“Right now, I am focused on understanding better the ‘climate-smartness’ of sustainable intensification technologies.”

In Malawi, Nyagumbo is part of a team evaluating the usefulness of different agronomic practices and indigenous methods to control fall armyworm in maize-based systems. Fall armyworm has been a troublesome pest particularly for maize in the last four or five seasons in eastern and southern Africa, and finding cost effective solutions is important for farmers in the region.

Future efforts are set to focus further on crop-livestock integration and will investigate how newly developed nutrient-dense maize varieties can contribute to improved feed for livestock in arid and semi-arid regions in Zimbabwe.

Sharing results

Another important aspiration for Nyagumbo is the generation of publications to share the emerging results and experiences gained from his research with partners and the public. Working in collaboration with others, Nyagumbo has published more than 30 articles based on extensive research work.

“Through the data sharing policy promoted by CIMMYT, we have so much data generated across the five SIMLESA project countries which is now available to the public who can download and use it,” Nyagumbo says.

While experiences with COVID-19 have shifted working conditions and restricted travel, Nyagumbo believes “through the use of virtual platforms and ICTs we can still achieve a lot and keep in touch with our partners and farmers in the region.”

Overall, he is interested in impact. “The greatest reward for me is seeing happy and transformed farmers on the ground, and knowing my role is making a difference in farmers’ livelihoods.”