It’s Rural Women’s Day, from dawn to dusk

Over 70% of rural women in India are engaged in agriculture. Women carry out a large portion of farm work, as cultivators and agricultural laborers, but in most cases they are not even counted and recognized as farmers. Millions of Indian rural women also carry the burden of domestic work, a job that is undervalued and unrecognized economically.

On the International Day of Rural Women, October 15, the focus is on their contributions to growing food and feeding families. The often invisible hands of rural women play a pivotal role in food security and sustaining rural communities.

Today, we have a glimpse at the daily life of farmer Anita Naik.

She hails from the village of Badbil, in the Mayurbhanj district of India’s Odisha state, surrounded by small hills and the lush greenery of Simlipal National Park.

Naik belongs to a tribal community that has long lived off the land, through farming and livestock rearing. Smallholder farmers like her grow rice, maize and vegetables in traditional ways — intensive labor and limited yield — to ensure food for their families.

Married at a young age, Naik has a son and a daughter. Her husband and her son are daily-wage laborers, but the uncertainty around their jobs and her husband’s chronic ill health means that she is mostly responsible for her family’s wellbeing. At 41, Naik’s age and her stoic expression belie her lifelong experience of hard work.

The small hours

Naik’s day begins just before dawn, a little past 4 a.m., with household chores. After letting out the livestock animals — goats, cows, chicken and sheep — for the day, she sweeps the house’s, the courtyard and the animal shed. She then lights the wood stove to prepare tea for herself and her family, who are slowly waking up to the sound of the crowing rooster. Helped by her young daughter, Naik feeds the animals and then washes the dirty dishes from the previous evening. Around 6:30 or 7 a.m., she starts preparing other meals.

During the lean months — the period between planting and harvesting — when farm work is not pressing, Naik works as a daily-wage worker at a fly ash brick factory nearby. She says the extra income helps her cover costs during emergencies. “[I find it] difficult to stay idle if I am not working on the farm,” she says. However, COVID-19 restrictions have affected this source of income for the family.

Once her morning chores are over, Naik works on her small plot of land next to her house. She cultivates maize and grows vegetables, primarily for household consumption.

Naik started growing maize only after joining a self-help group in 2014, which helped her and other women cultivate hybrid maize for commercial production on leased land. They were supported by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) through the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) maize intensification program.

Every year from June to October, Naik also work on this five-acre leased farmland, along with the other group members. She is involved from planting to harvest — and even in marketing.

“There are eleven women members in our self-help group, Biswa Jay Maa Tarini. Thanks to training, awareness and handholding by CSISA and partners, an illiterate like me is currently the president of our group,” said an emotional Anita Naik.

Not quite done yet

A little further away from her house, Naik has a small field where she grows rice with the help of her husband and son. After checking in on her maize crop on the leased land, Naik works in her paddy the rest of the day. She tends to her land diligently, intent on removing the weeds that keep springing up again and again in the monsoon season.

“It is back-breaking work, but I have to do it myself as I cannot afford to employ a laborer,” Naik laments.

Naik finally takes a break around 1 p.m. for lunch. Some days, particularly in the summer when exhaustion takes over, she takes a short nap before getting back to removing weeds in the rice fields.

She finally heads home around 4 p.m. At home, she first takes the animals back into their shed.

Around 6 p.m., she starts preparing for dinner. After dinner, she clears the kitchen and the woodstove before calling it a night and going to bed around 8 or 9 p.m.

“The day is short and so much still needs to be done at home and in the field,” Naik says after toiling from early morning until evening.

Tomorrow is a new day, but chores at home and the work in the fields continue for Naik and farmers like her.

Paradigm change

Traditionally farmers in and around Naik’s village cultivated paddy in their uplands for personal consumption only, leaving the land fallow for the rest of the year. Growing rice is quite taxing as paddy is a labor-intensive crop at sowing, irrigating, weeding and harvesting. With limited resources, limited knowledge and lack of appropriate machinery, yields can vary.

To make maximum use of the land all year through and move beyond personal consumption and towards commercial production, CIMMYT facilitated the adoption of maize cultivation. This turned out to be a gamechanger, transforming the livelihoods of women in the region and often making them the main breadwinner in their families.

In early 2012, through the CSISA project, CIMMYT began its sustainable intensification program in some parts of Odisha’s plateau region. During the initial phase, maize stood out as an alternative crop with a high level of acceptance, particularly among women farmers.

Soon, CIMMYT and its partners started working in four districts — Bolangir, Keonjhar, Mayurbhanj and Nuapada — to help catalyze the adoption of maize production in the region. Farmers shifted from paddy to maize in uplands. At present, maize cultivation has been adopted by 7,600 farmers in these four districts, 28% of which are women.

CIMMYT, in partnership with state, private and civil society actors, facilitated the creation of maize producers’ groups and women self-help groups. Getting together, farmers can standardize grain quality control, aggregate production and sell their produce commercially to poultry feed mills.

This intervention in a predominantly tribal region significantly impacted the socioeconomic conditions of women involved in this project. Today, women like Anita Naik have established themselves as successful maize farmers and entrepreneurs.

Cover photo: Farmer Anita Naik stands for a photograph next to her maize field. (Photo: Nima Chodon/CIMMYT)

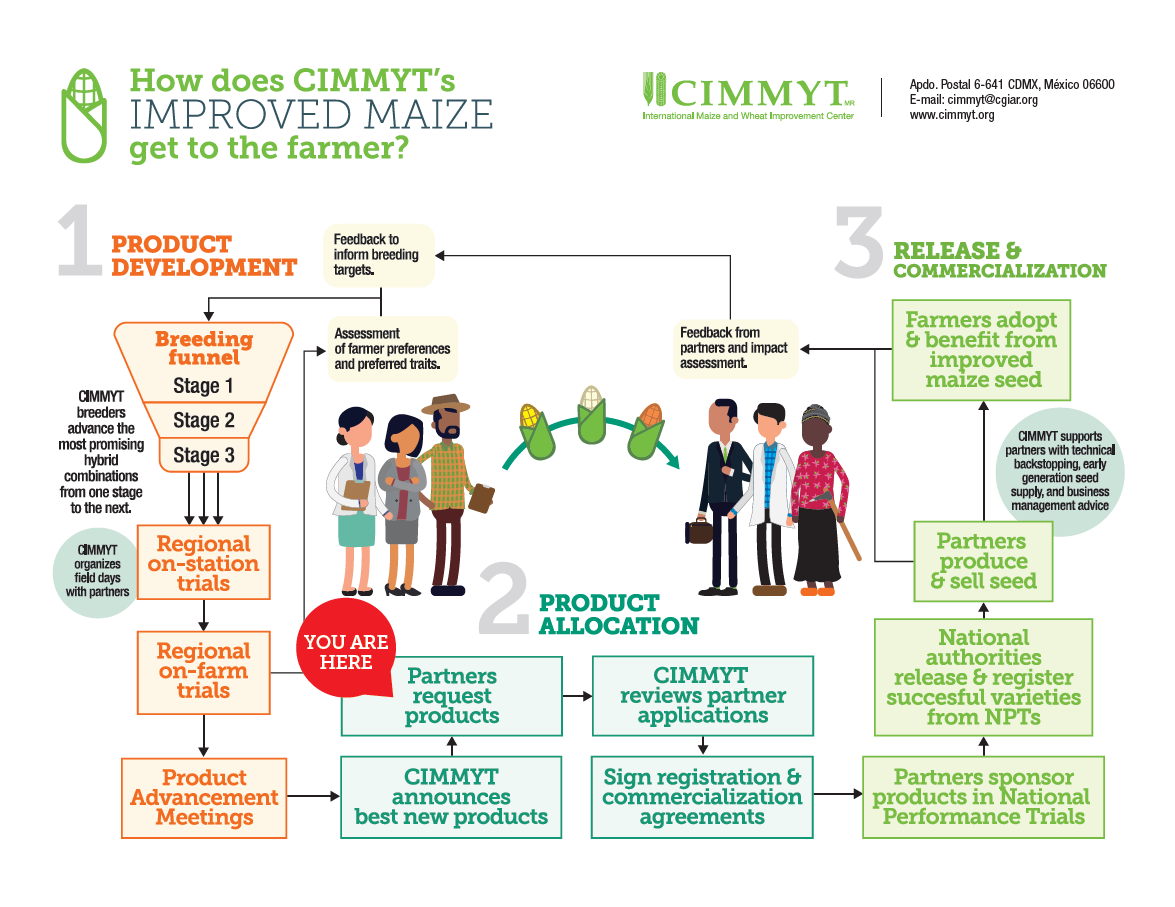

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is offering a new set of elite, improved maize hybrids to partners for commercialization in southern Africa and similar agro-ecological zones. National agricultural research systems (NARS) and seed companies are invited to apply for licenses to register and commercialize these new hybrids, in order to bring the benefits of the improved seed to farming communities.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is offering a new set of elite, improved maize hybrids to partners for commercialization in southern Africa and similar agro-ecological zones. National agricultural research systems (NARS) and seed companies are invited to apply for licenses to register and commercialize these new hybrids, in order to bring the benefits of the improved seed to farming communities.