Fast-tracked adoption of second-generation resistant maize varieties key to managing maize lethal necrosis in Africa

Scientists are calling for accelerated adoption of new hybrid maize varieties with resistance to maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease in sub-Saharan Africa. In combination with recommended integrated pest management practices, adopting these new varieties is an important step towards safeguarding smallholder farmers against this devastating viral disease.

A new publication in Virus Research shows that these second-generation MLN-resistant hybrids developed by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) offer better yields and increased resilience against MLN and other stresses. The report warns that the disease remains a key threat to food security in eastern Africa and that, should containment efforts slacken, it could yet spread to new regions in sub-Saharan Africa.

The publication was co-authored by researchers at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) and Aarhus University in Denmark.

Stemming the panic

The first reported outbreak of MLN in Bomet County, Kenya in 2011 threw the maize sector into a panic. The disease caused up to 100% yield loss. Nearly all elite commercial maize varieties on the market at the time were susceptible, whether under natural of artificial conditions. Since 2012, CIMMYT, in partnership with KALRO, national plant protection organizations and commercial seed companies, has led multi-stakeholder, multi-disciplinary efforts to curb MLN’s spread across sub-Saharan Africa. Other partners in this endeavor include the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), non-government organizations such as AGRA and AATF, and advanced research institutions in the United States and Europe.

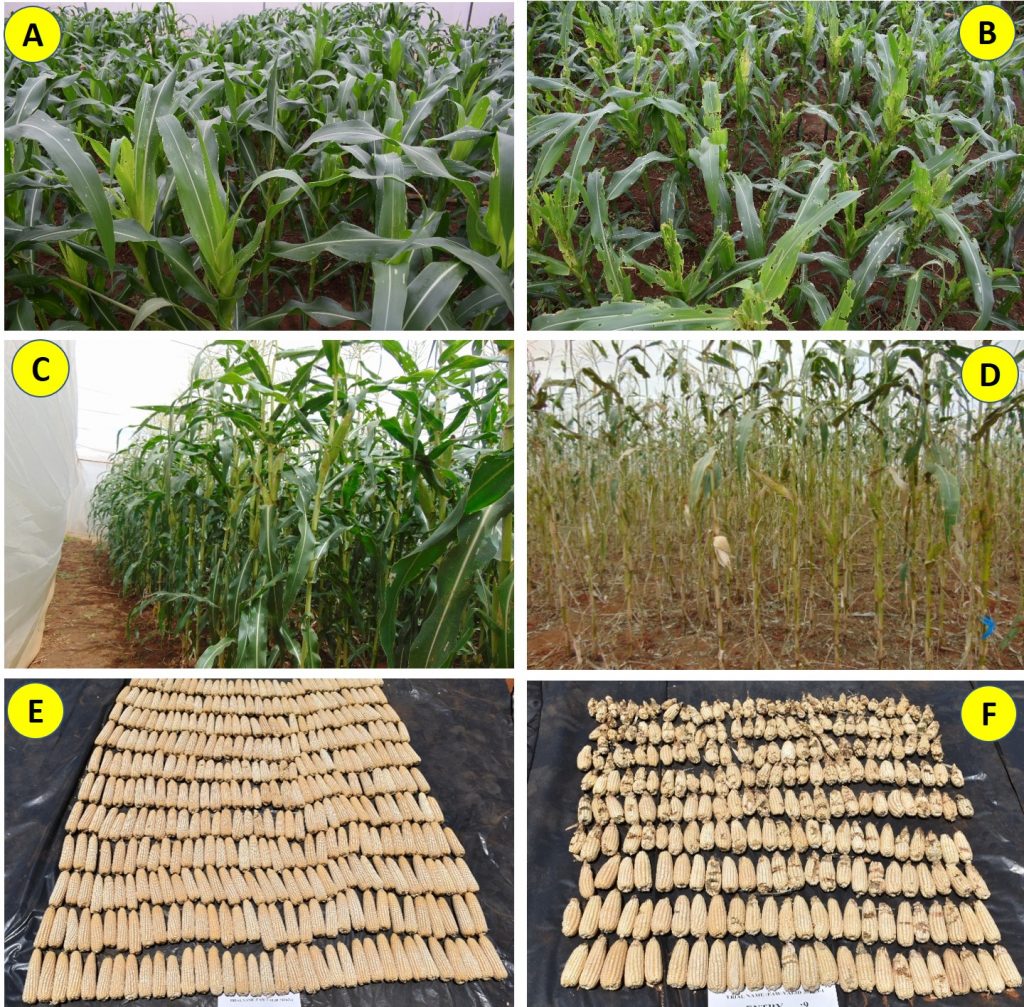

In 2013 CIMMYT established an MLN screening facility in Naivasha. Researchers developed an MLN-severity scale, ranging from 1 to 9, to compare varieties’ resistance or susceptibility to the disease. A score of 1 represents a highly resistant variety with no visible symptoms of the disease, while a score of 9 signifies extreme susceptibility. Trials at this facility demonstrated that some of CIMMYT’s pre-commercial hybrids exhibited moderate MLN-tolerance, with a score of 5 on the MLN-severity scale. CIMMYT then provided seed and detailed information to partners for evaluation under accelerated National Performance Trials (NPTs) for varietal release and commercialization in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

Between 2013 and 2014, four CIMMYT-derived MLN-tolerant hybrid varieties were released by public and private sector partners in East Africa. With an average MLN severity score of 5-6, these varieties outperformed commercial MLN-sensitive hybrids, which averaged MLN severity scores above 7. Later, CIMMYT breeders developed second-generation MLN-resistant hybrids with MLN severity scores of 3–4. These second-generation hybrids were evaluated under national performance trials. This led to the release of several hybrids, especially in Kenya, over the course of a five-year period starting in 2013. They were earmarked for commercialization in East Africa beginning in 2020.

Widespread adoption critical

The last known outbreak of MLN was reported in 2014 in Ethiopia, marking an important break in the virus’s spread across the continent. Up to that point, the virus had affected the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. However, much remains to be done to minimize the possibility of future outbreaks.

“Due to its complex and multi-faceted nature, effectively combating the incidence, spread and adverse effects of MLN in Africa requires vigorous and well-coordinated efforts by multiple institutions,” said B.M. Prasanna, primary author of the report and director of the Global Maize Program at CIMMYT and of the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE). Prasanna also warns that most commercial maize varieties being cultivated in eastern Africa are still MLN-susceptible. They also serve as “reservoirs” for MLN-causing viruses, especially the maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV), which combines with other viruses from the Potyviridae family to cause MLN.

“This is why it is very important to adopt an integrated disease management approach, which encompasses extensive adoption of improved MLN-resistant maize varieties, especially second-generation, not just in MLN-prevalent countries but also in the non-endemic ones in sub-Saharan Africa,” Prasanna noted.

The report outlines other important prevention and control measures including: the production and exchange of “clean” commercial maize seed with no contamination by MLN-causing viruses; avoiding maize monocultures and continuous maize cropping; practicing maize crop rotation with compatible crops, especially legumes, which do not serve as hosts for MCMV; and continued MLN disease monitoring and surveillance.

Noteworthy wins

In addition to the development of MLN-resistant varieties, the fight against MLN has delivered important wins for both farmers and their families and for seed companies. In the early years of the outbreak, most local and regional seed companies did not understand the disease well enough to produce MLN-pathogen free seed. Since then, CIMMYT and its partners developed standard operating procedures and checklists for MLN pathogen-free seed production along the seed value chain. Today over 30 seed companies in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania are implementing these protocols on a voluntary basis.

“MLN represents a good example where a successful, large-scale surveillance system for an emerging transboundary disease has been developed as part of a rapid response mechanism led by a CGIAR center,” Prasanna said.

Yet, he noted, significant effort and resources are still required to keep the maize fields of endemic countries free of MLN-causing viruses. Sustaining these efforts is critical to the “food security, income and livelihoods of resource-poor smallholder farmers.

To keep up with the disease’s changing dynamics, CIMMYT and its partners are moving ahead with novel techniques to achieve MLN resistance more quickly and cheaply. Some of these innovative techniques include genomic selection, molecular markers, marker-assisted backcrossing, and gene editing. These techniques will be instrumental in developing elite hybrids equipped not only to resist MLN but also to tolerate rapidly changing climatic conditions.

Read the full report on Virus Research:

Maize lethal necrosis (MLN): Efforts toward containing the spread and impact of a devastating transboundary disease in sub-Saharan Africa

Cover photo: Researchers and visitors listen to explanations during a tour of infected maize fields at the MLN screening facility in Naivasha, Kenya. (Photo: CIMMYT)