Building a sustainable hybrid seed market system in Nepal to enhance food security and farmers’ profitability: transforming the seed sector through local capacity development

Nepal, a Himalayan nation with substantial agricultural potential, has a maize seed market valued at over $100 million. Yet in 2023, only 15% of the national demand for quality maize seed was met. Historically, the country has relied heavily on imports to supply hybrid maize seeds, which account for approximately 15–20% of the cultivated maize area.

To address this challenge, CIMMYT, in collaboration with the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) and local private seed companies, has embarked on a transformative journey to strengthen domestic hybrid maize seed production and marketing systems. The results have been impressive: winter-season hybrid seed production has increased from just 4.5 metric tons in 2018 — when local hybrid seed efforts began — to 200 metric tons by 2023/24. This growth has been fueled by hybrid maize varieties developed by CIMMYT and released by NARC, which continue to drive this upward trend.

Manesh Patel, President of Asia and Pacific Seed Association (APSA), reflected on his experience on Nepal’s evolving seed industry during the recent International Seed Conference in Kathmandu: “About 10 or 12 years ago, I had the opportunity to interact with the seed stakeholders in Nepal. At that time, the seed sector was not viable, and the role of the private sector was minimal. Now, I am impressed to see such transformative initiatives in Nepal’s seed sector.”

Patel acknowledged the vital role of CIMMYT and other stakeholders, particularly under the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer Project (NSAF) in driving this transformation. The local seed companies have been instrumental in scaling hybrid seed production, by leveraging the technical, human, and institutional capacity development support provided by CIMMYT and partners.

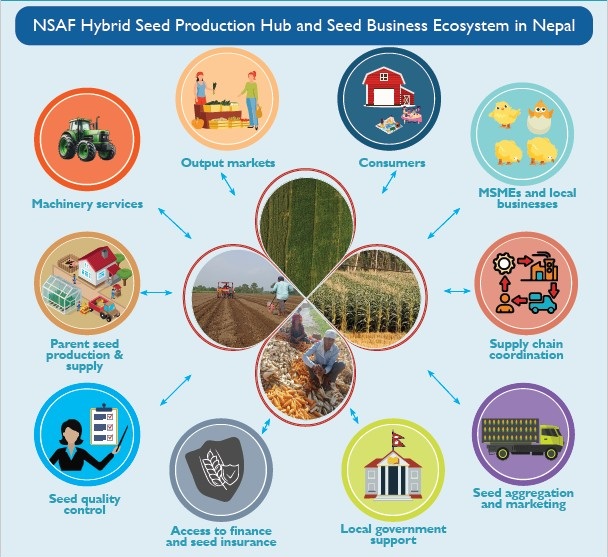

Hybrid seed production hubs — a model to foster agile seed business

Under the NSAF project, CIMMYT partnered with ten Nepalese seed companies and farmers’ cooperatives to establish hybrid seed production hubs. Previously, companies operated in a fragmented and inefficient manner, resulting in elevated production costs. To address this, the project identified strategic production hubs where farmers could pool their land and produce seeds in an adjacent, coordinated seed production. The districts of Dang, Kapilvastu, and Kailali emerged as key hubs, now hosting at least six seed companies working collaboratively to streamline hybrid maize seed production.

Spearheaded by collaborative efforts between public and private stakeholders, these hubs are contributing to Nepal’s seed sector by centralizing resources, technology, and expertise. Since 2020/21, these hubs have served as key focal points for the production of quality hybrid seeds and for advancing improvements across the seed value chain. Notable outcomes of the model include:

- Bringing breeders, agronomists, and technical experts together for knowledge transfer and streamlined seed multiplication which enhances efficiency.

- Enhancing seed quality through centralized facilities, and land pooling, which reduces cross-contamination of the seed field and ensures rigorous quality control.

- Reducing costs through centralized operations, which lowers production cost and makes hybrid seeds more affordable and accessible.

- Strengthening the supply chain helps to enhance timely seed availability.

The Dang hub stands as a testament to the success of Nepal’s emerging hybrid seed production model. Between 2020/21 and 2023/24, the production area expanded by more than 300%, seed production rose by an impressive 1,450%, and farmer participation increased by 290%.

This extraordinary growth was made possible through a strong public-private ecosystem, including support from the Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project (PMAMP), which facilitated mechanization as seed companies scaled their operations. In 2023/24 alone, the hub produced enough hybrid maize seed to plant 10,000 hectares — yielding nearly $25 million in grain value that would otherwise have been met through costly imports.

Tripling farmers’ incomes and creating rural job opportunities

Nepal faces significant rural outmigration, as economic pressures and shifting aspirations drive many men and youth to seek opportunities elsewhere leading to depopulation and increasing abandonment of farmland. In their absence, women now comprise an estimated 60–70% of the rural workforce, often balancing farm labor with household responsibilities. Amid these challenges, the hybrid seed business model is proving transformative. By enabling farmers to generate higher returns from smaller plots and creating rural employment opportunities for both women and men, it offers a path to revitalizing rural livelihoods and strengthening local economies.

Farmers like Ganesh Choudhary and Yuvraj Chaudhary exemplify this success. Ganesh transitioned from wheat farming to hybrid maize seed production at the Kailali hub under a contract with Unique Seed Company. In just one season, his income tripled, earning $1,980 compared to $660 from wheat on the same plot of land. Similarly, Yuvraj, working with Gorkha Seed Company at the Dang hub, earned $2,400 in his second year, three times more than his previous income—after receiving targeted training and technical support.

Additionally, key operations in hybrid seed production, such as detasseling and roughing, have created employment opportunities for rural women, who manage over 60% of these tasks. The financial security offered by buyback guarantees from the seed companies, combined with the efficiency of clustered land management, has provided farmers with a more sustainable pathway to improved livelihoods. This approach not only addresses economic challenges but also helps curb migration and empowers rural communities.

Maintaining the momentum

The modest beginnings of hybrid seed production are ushering in a new era for Nepal’s seed sector and represent a beacon of hope for its broader agricultural transformation. By effectively integrating seed companies, public research institutions, cooperatives, and government support, Nepal is poised to build a resilient seed market system — one that enhances farmer livelihoods and bolsters the national economy.

To sustain and consolidate these gains, continued collaboration and partnership among stakeholders is essential. Building on the strong foundation laid and maintaining momentum will require, among other efforts:

- Policy support by the government to encourage hybrid seed production and provide necessary resources, particularly to hybrid seed startups.

- Foster private sector engagement and strengthen partnerships with seed companies to ensure long-term market viability.

- Institutional capacity building and investment in training programs for farmers, agronomists, and technical staff to maintain and enhance the quality of hybrid seeds.

- Strengthening research and development, particularly to develop and deploy new hybrid varieties suited to diverse agro-ecological zones and market segments.

- Enhance financial access to credit and insurance for seed companies, seed growers to mitigate risks and encourage investment.

The remarkable progress in hybrid seed production driven by coordinated public-private efforts marks a pivotal shift for Nepal’s agricultural future. Beyond reducing dependence on costly imports, this momentum is laying the foundation for a resilient, self-sufficient seed sector. It holds the promise of greater food security, increased farmer incomes, and long-term sustainability. With continued investment and collaboration, Nepal is not only transforming its seed systems but also empowering its rural communities and securing a more prosperous agricultural economy for generations to come.