Stronger African seed sector to benefit smallholder farmers and economy

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) – Africa’s agriculture sector is driven by smallholder farmers who also account for 70 percent of people directly reliant on agriculture for their livelihoods. Despite its large-scale impact across the continent, smallholder farming largely remains a low technology, subsistence activity.

Constructively engaging smallholders as investors as well as producers can help attract better investment into the sector, engaging farmers to produce bigger crops for sale rather than only for consumption at the household level. To achieve this goal, bigger financial investments are required to raise the standard of engagement and consequently that of Africa’s agricultural sector, according to Paswel Marenya, a social scientist who works with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT),

Three recent studies conducted by CIMMYT scientists and their collaborators in eastern and southern Africa assessed potential interventions to address current inefficiencies in seed supply chains. They also explored how low purchasing power has hobbled smallholders trying to gain access to maize and legume seed markets. Even though these markets have recently expanded as more private companies invest in maize and legume businesses, smallholders have not benefited despite their significant role in the sector.

A key component of improving agricultural practices is to bolster seed systems to give smallholders better access to high-yielding, stress tolerant seeds. For example, in Tanzania, a weak seed supply chain led to smallholders recycling hybrid maize seeds up to three years in a row in some cases. The main source of legume seeds was often from seed saved from previous harvest.

Elsewhere, in Mozambique, smallholders surveyed were accessing only three improved varieties in 2014 despite the release of over 30 improved maize and legume varieties that year. In a country where 95 percent of the population is dependent on maize and legumes, which particularly for rural families provide the most important source of proteins, deep changes are needed to facilitate access to improved seeds.

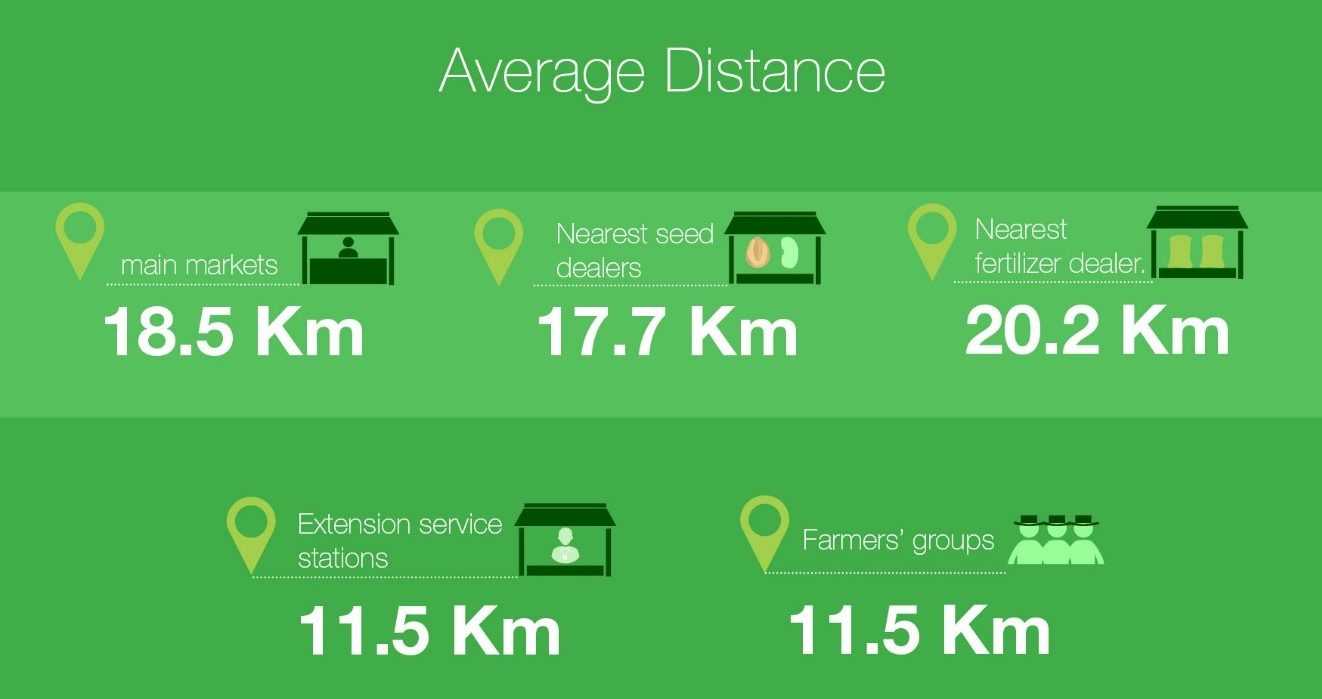

The studies determined that ineffective seed distribution contributed significantly to limiting smallholder access to improved varieties. Additionally, low seed production from the few approved seed companies in the country has worsened the situation due to soaring costs, putting improved seed beyond the reach of millions of smallholders.

As a result, approximately 70 percent of Mozambican farmers use local maize varieties with poor resistance to pests and diseases and low productivity potential.

To address these issues, the studies unanimously recommend investments in rural roads to connect isolated communities with agricultural and seed markets and to make it more cost effective for seed distributors to reach far flung communities. Secondly, investments in storage facilities in Mozambique and a more effective national seed system are needed to facilitate adequate foundation seed for seed companies. In addition to favorable policies that attract more private seed and fertilizer companies, a stronger public agricultural extension system is required.

On a broader scale, government policymakers must take advantage of the burgeoning seed sector and mushrooming interest from private sector players.

“Regulatory agencies in the seed sector should take up a bigger role to facilitate and encourage competition that will widen seed access and bring down seed costs,” Marenya said. “This is the most sustainable solution that ensures the private sector is involved, farmers drive seed demand, and profit prospects are good.”

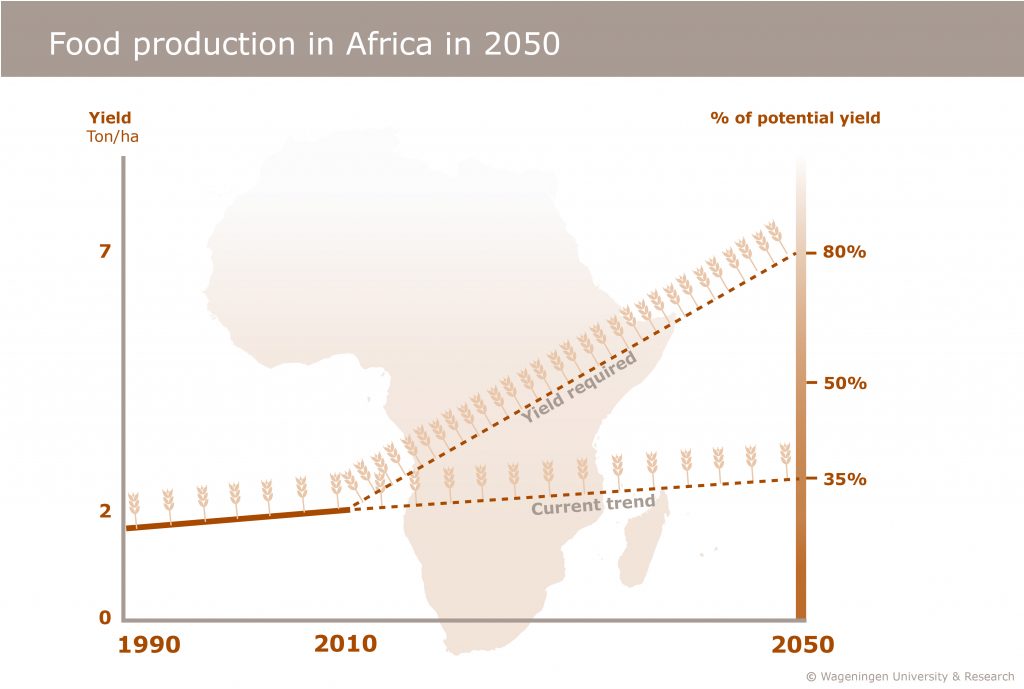

Rising food demand and projected growth of African food markets present a real opportunity for African farmers, Marenya added. In 2011, for example, sub-Saharan Africa imported $43 billion worth of such basic agricultural commodities as wheat, rice, maize, vegetable oil and sugar. Additionally, research estimates from Germany’s Deutsche Bank show that urban food markets will quadruple and that food and beverage markets are projected to grow to about $1 trillion by 2030 leading to bigger economic benefits overall.

While staple crop markets in the eastern and southern Africa region are relatively vibrant, many farmers gain access to these markets through informal links. Structured value chains, which include dependable and transparent information systems, quality storage facilities and supportive financial or credit services would enhance farmers’ role in the markets.

“Real change will occur when efforts be made to enable farmers and traders to profitably invest in superior pre- and post-harvest quality management as well as engage in contract-based supply chains to exploit opportunities brought about by increasing urbanization and trade,” Marenya said.

Read more about the three studies: