Global maize experts discuss biofortification for nutrition and health

Over two billion people across the world suffer from hidden hunger, the consumption of a sufficient number of calories, but still lacking essential nutrients such as vitamin A, iron or zinc. This can cause severe damage to health, blindness, or even death.

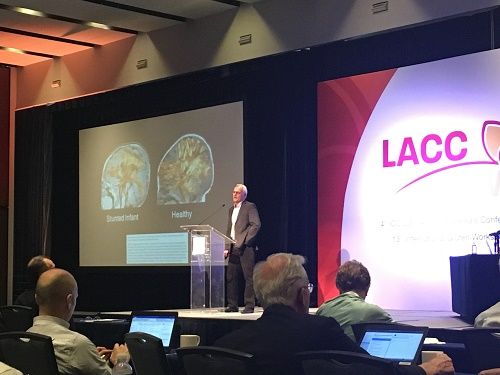

At the 4th annual Latin American Cereals Conference (LACC) in Mexico City from 11 to 14 March, presenters discussed global malnutrition and how biofortification of staple crops can be used to improve nutrition for farming families and consumers.

“A stunted child will never live up to its full potential,” said Wolfgang Pfeiffer, director of research and development at HarvestPlus, as he showed a slide comparing the brain of a healthy infant versus a stunted one.

Hidden hunger and stunting, or impaired development, are typically associated with poverty and diets high in staple crops such as rice or maize. Biofortification of essential nutrients into these staple crops has the potential to reduce malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies around the world.

“Maize is a staple crop for over 900 million poor consumers, including 120-140 million poor families. Around 73% of farmland dedicated to maize production worldwide is located in the developing world,” said B.M. Prasanna, director of the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE) at LACC.

The important role of maize in global diets and the rich genetic diversity of the crop has allowed for important breakthroughs in biofortifcation. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) has over 40 years of experience in maize breeding for biofortification, beginning with quality protein maize (QPM), which has enhanced levels of lysine and tryptophan, essential amino acids, which can help reduce malnutrition in children.

“Over 50 QPM varieties have been adopted in Latin America and the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, and three new QPM hybrids were released in India in 2017 using marker assisted breeding,” said Prasanna.

In more recent years, CIMMYT has worked with MAIZE and HarvestPlus to develop provitamin A maize to reduce vitamin A deficiency, the leading cause of preventable blindness in children, affecting 5.2 million preschool-age children globally, according to the World Health Organization. This partnership launched their first zinc-enriched maize varieties in Honduras in 2017 and Colombia in 2018, with releases of new varieties planned in Guatemala and Nicaragua later this year. Zinc deficiency can lead to impaired growth and development, respiratory infections, diarrheal disease and a general weakening of the immune system.

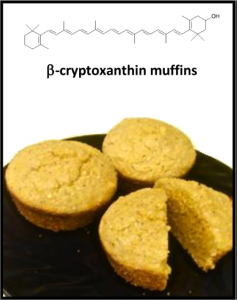

“There is a huge deficiency of vitamin A, iron and zinc around the world,” said Natalia Palacios, maize nutritional quality specialist at CIMMYT. “The beauty of maize is its huge genetic diversity that has allowed us to develop these biofortified varieties using conventional breeding methods. The best way to take advantage of maize nutritional benefits is through biofortification, processing and functional food,” she said.

The effects of these varieties are already beginning to show. Recent studies have shown that vitamin A maize improves vitamin A status and night vision of 4-8 year old rural children in Zambia.

“Biofortified crops are in testing in over 60 countries, 7.5 million households are growing biofortified crops, and over 35 million household members are consuming them,” said Pfeiffer. “It is critical to involve farmers in the development of biofortified crop varieties before they are released, through participatory variety selection.”

Overall, the conference presenters agreed that ending hidden hunger will require cooperation and partnerships from multiple sectors and disciplines. “Partnerships with seed companies are crucial for biofortified maize to make an impact. This is not just about technological advances and developing new products, this is about enabling policies, stimulating demand, and increasing awareness about the benefits of these varieties,” said Prasanna.

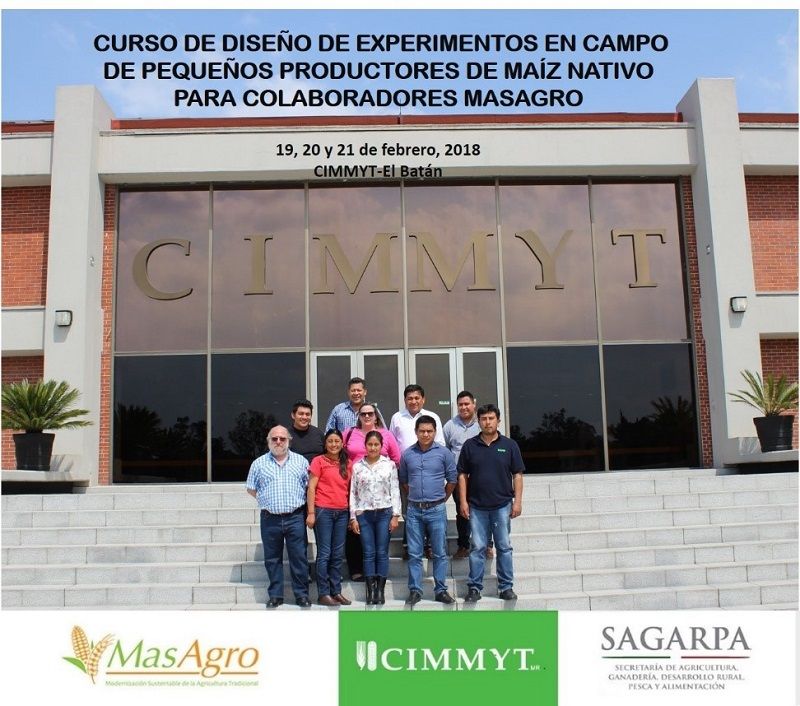

As part of the efforts of the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program aimed at improving food security based on maize landraces in marginal areas of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, a workshop on trial design was held from 19-21 February to improve the precision of data on improved maize landraces in smallholder farmers’ fields. Attending the workshop were partners from the National Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research Institute (INIFAP) and the Southern Regional University Center of the Autonomous University of Chapingo (UACh).

As part of the efforts of the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program aimed at improving food security based on maize landraces in marginal areas of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, a workshop on trial design was held from 19-21 February to improve the precision of data on improved maize landraces in smallholder farmers’ fields. Attending the workshop were partners from the National Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research Institute (INIFAP) and the Southern Regional University Center of the Autonomous University of Chapingo (UACh).