Millions at lower risk of vitamin A deficiency after six-year campaign to promote orange-fleshed sweet potato

STOCKHOLM, Sweden — Millions of families in Africa and South Asia have improved their diet with a special variety of sweet potato designed to tackle vitamin A deficiency, according to a report published today.

A six-year project, launched in 2013, used a double-edged approach of providing farming families with sweet potato cuttings as well as nutritional education on the benefits of orange-fleshed sweet potato.

The Scaling Up Sweetpotato through Agriculture and Nutrition (SUSTAIN) project, led by the International Potato Center (CIP) and more than 20 partners, reached more than 2.3 million households with children under five with planting material.

The project, which was rolled out in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique and Rwanda as well as Bangladesh and Tanzania, resulted in 1.3 million women and children regularly eating orange-fleshed sweet potato when available.

“Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is one of the most pernicious forms of undernourishment and can limit growth, weaken immunity, lead to blindness, and increase mortality in children,” said Barbara Wells, director general of CIP. “Globally, 165 million children under five suffer from VAD, mostly in Africa and Asia.”

“The results of the SUSTAIN project show that agriculture and nutrition interventions can reinforce each other to inspire behavior change towards healthier diets in smallholder households.”

Over the past decade, CIP and partners have developed dozens of biofortified varieties of orange-fleshed sweet potato in Africa and Asia. These varieties contain high levels of beta-carotene, which the body converts into vitamin A.

Just 125g of fresh orange-fleshed sweet potato provides the daily vitamin A needs of a pre-school child, as well as providing high levels of vitamins B6 and C, manganese and potassium.

Under the SUSTAIN project, families in target communities received nutritional education at rural health centers as well as cuttings that they could then plant and grow.

For every household directly reached with planting material, an additional 4.2 households were reached on average through farmer-to-farmer interactions or partner activities using technologies or materials developed by SUSTAIN.

The project also promoted commercial opportunities for smallholder farmers with annual sales of orange-fleshed sweet potato puree-based products estimated at more than $890,000 as a result of the project.

Perspectives from the Global South

The results of the initiative were published during the EAT Forum in Stockholm, where CGIAR scientists discussed the recommendations of the EAT-Lancet report from the perspective of developing countries.

“The SUSTAIN project showed the enormous potential for achieving both healthy and sustainable diets in developing countries using improved varieties of crops that are already widely grown,” said Simon Heck, program leader, CIP.

“Sweet potato should be included as the basis for a sustainable diet in many developing countries because it provides more calories per hectare and per growing month than all the major grain crops, while tackling a major nutrition-related health issue.”

At an EAT Forum side event, scientists highlighted that most food is grown by small-scale producers in low- and middle-income countries, where hunger and undernutrition are prevalent and where some of the largest opportunities exist for food system and dietary transformation.

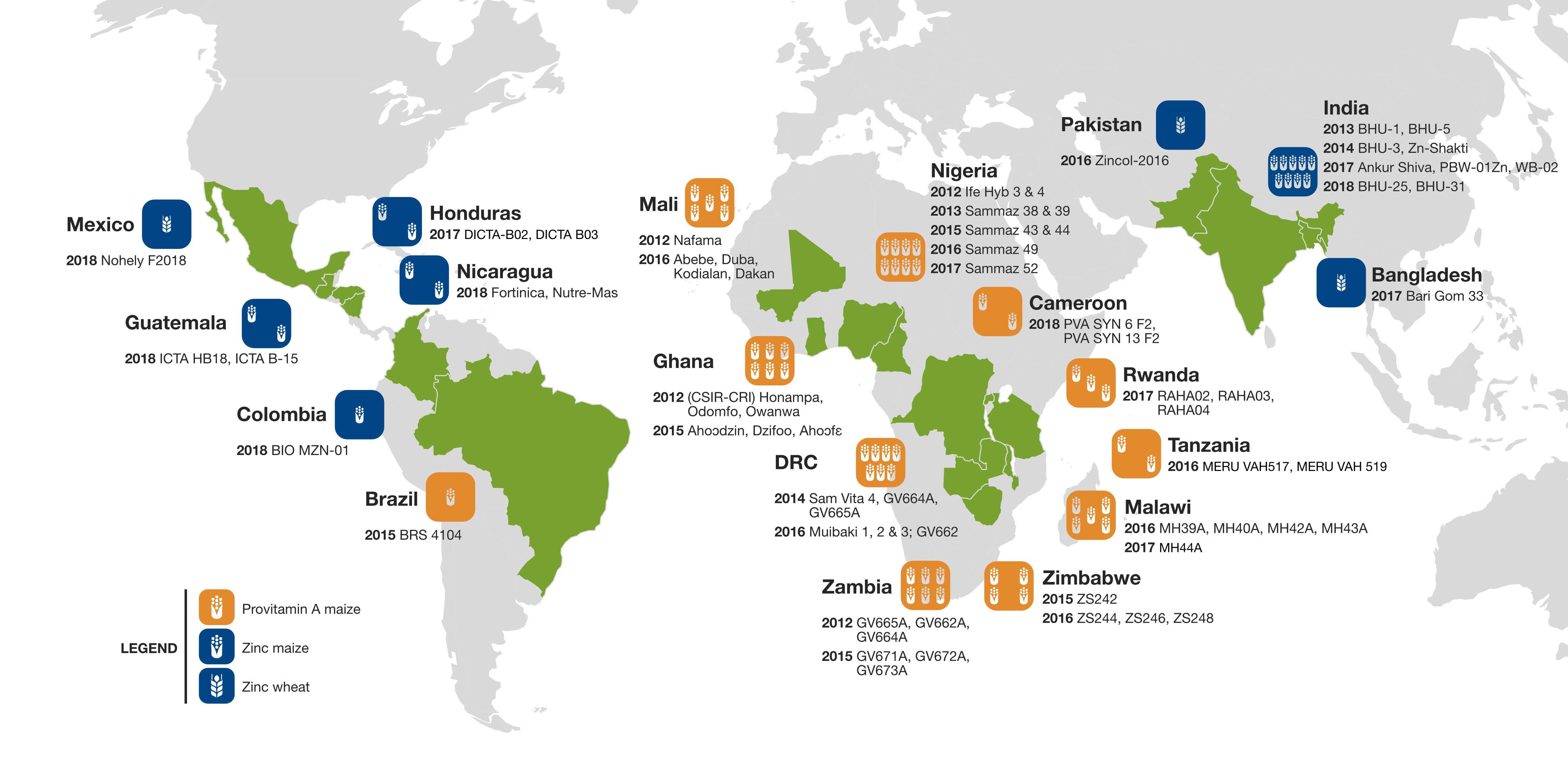

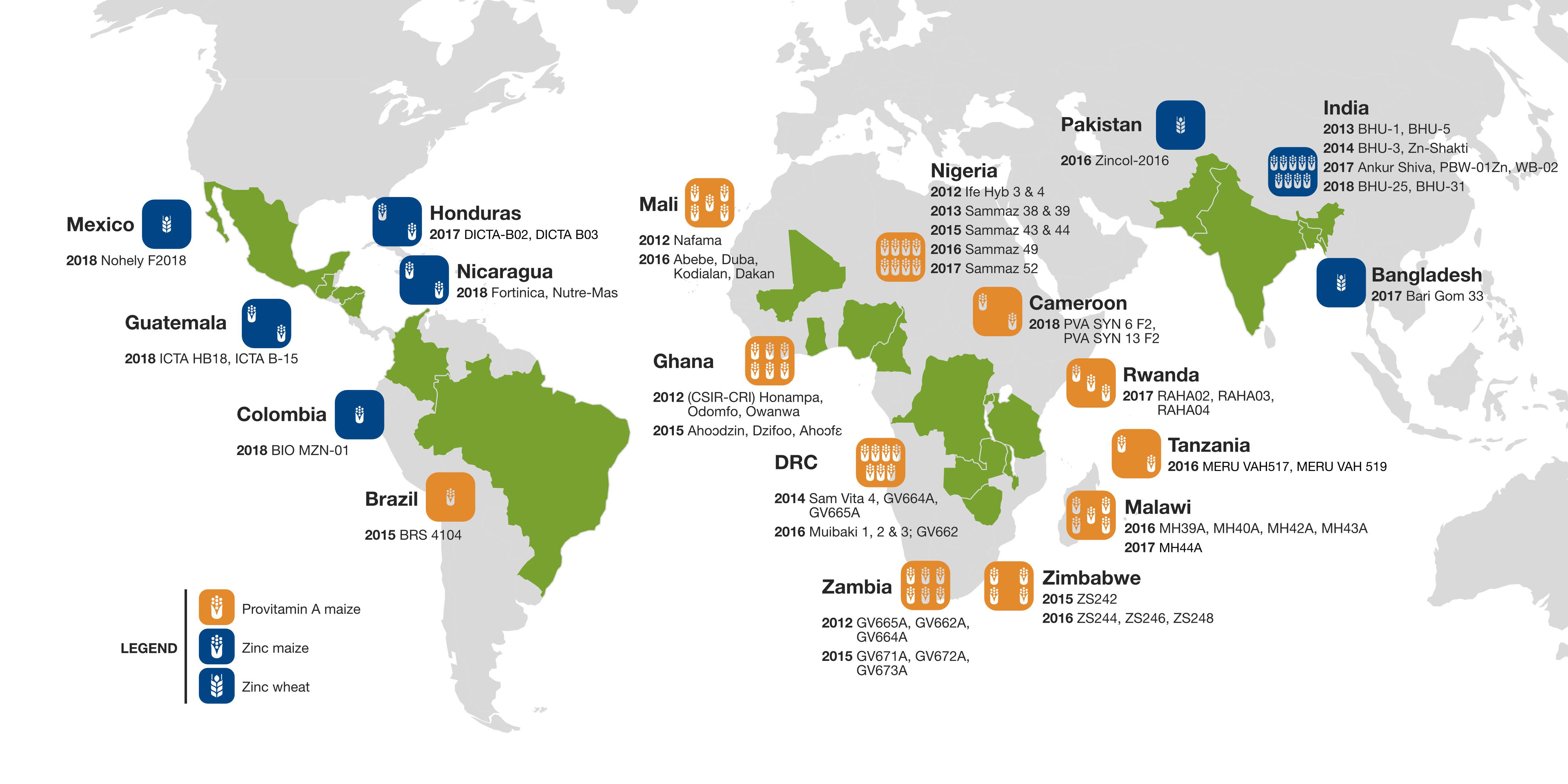

“There are almost 500 million small farms that comprise close to half the world’s farmland and are home to many of the world’s most vulnerable populations,” said Martin Kropff, director general of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

“Without access to appropriate technologies and support to sustainably intensify production, small farmers — the backbone of our global food system — will not be able to actively contribute a global food transformation.”

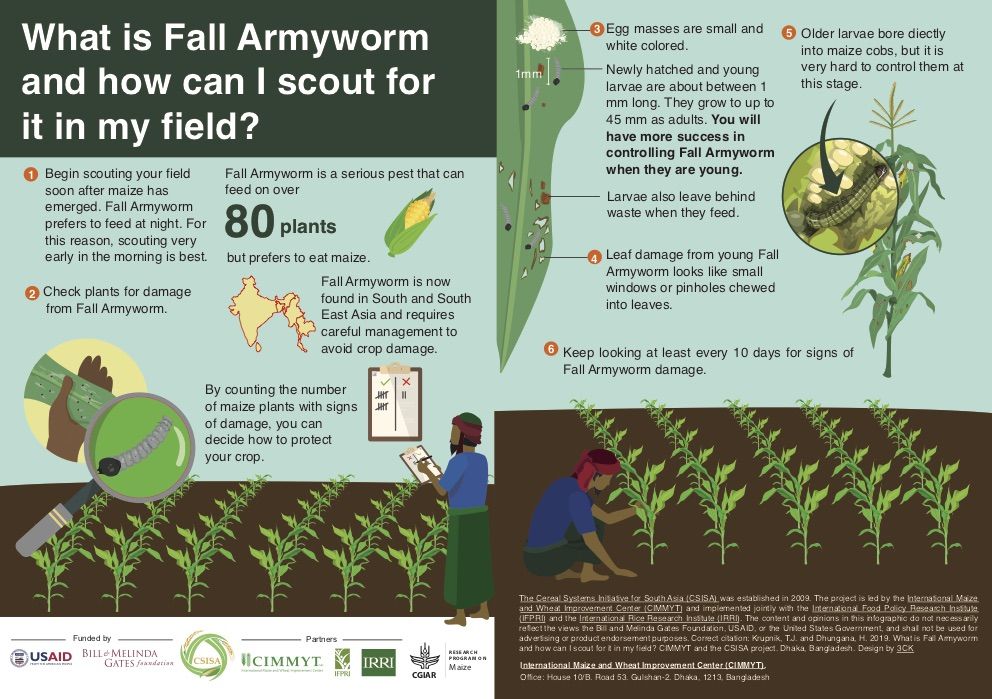

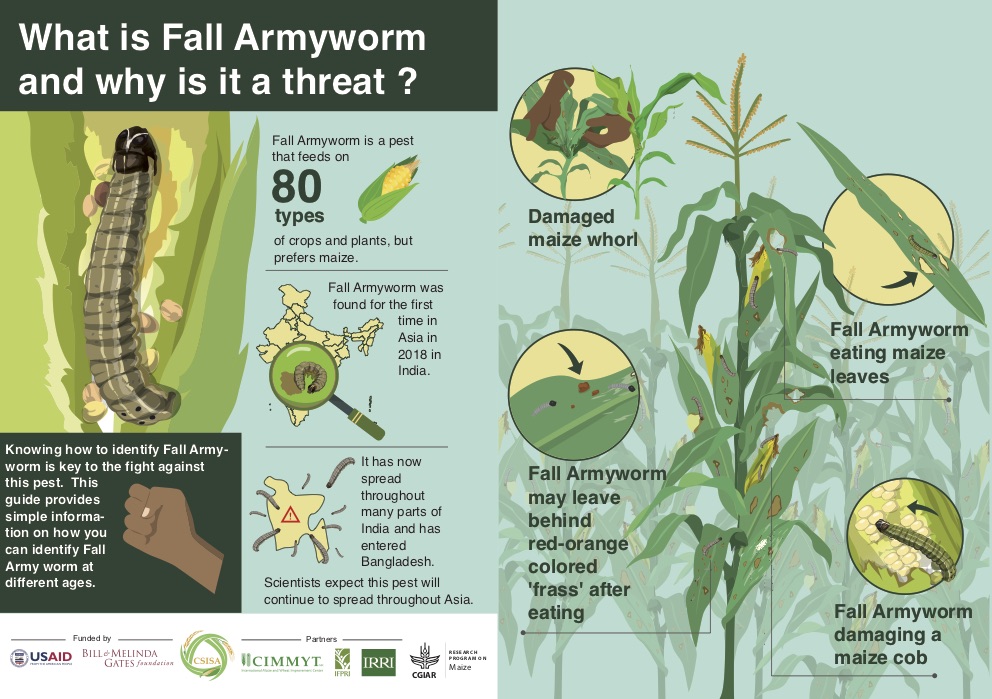

Matthew Morell, director general of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), added: “If the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet guidelines are to be truly global, they will need to be adapted to developing-world realities — such as addressing Vitamin A deficiency through bio-fortification of a range of staple crops.

“This creative approach is a strong example of how to address a devastating and persistent nutrition gap in South Asia and Africa.”

This story is part of our coverage of the EAT Stockholm Food Forum 2019.

See other stories and the details of the side event in which CIMMYT is participating.

For more information or interview requests, please contact:

Donna Bowater

Marchmont Communications

donna@marchmontcomms.com

+44 7929 212 434

The International Potato Center (CIP) was founded in 1971 as a research-for-development organization with a focus on potato, sweet potato and Andean roots and tubers. It delivers innovative science-based solutions to enhance access to affordable nutritious food, foster inclusive sustainable business and employment growth, and drive the climate resilience of root and tuber agri-food systems. Headquartered in Lima, Peru, CIP has a research presence in more than 20 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. CIP is a CGIAR research center. www.cipotato.org

CGIAR is a global research partnership for a food-secure future. CGIAR science is dedicated to reducing poverty, enhancing food and nutrition security, and improving natural resources and ecosystem services. Its research is carried out by 15 CGIAR centers in close collaboration with hundreds of partners, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia, development organizations and the private sector. www.cgiar.org