Include small indigenous production systems to improve rural livelihoods

Researchers from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee, United States, and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Texcoco, Mexico, describe why it is important for technical assistance to build upon indigenous farming knowledge and include women if programs are to succeed in tackling poverty and hunger in rural, Mesoamerican communities. Their findings, describing recent work in the Guatemalan Highlands, are recently published in Nature Sustainability.

According to government figures, 59% of Guatemalans live in poverty, concentrated in indigenous rural areas, such as the Western Highlands. Many factors contribute to pervasive malnutrition and a lack of employment opportunities for people in the Highlands. Recent crop failures associated with atypical weather events have exacerbated food shortages for Highland farm communities.

In early 2019, 90% of recent migrants to the southern border of the United States were from Guatemala, a majority of those from regions such as the Western Highlands. When they are unable to produce or purchase enough food to feed their families, people seek opportunities elsewhere. Historically, sugar cane and coffee industries offered employment but as prices for these commodities fall, fewer options for work are available within the region.

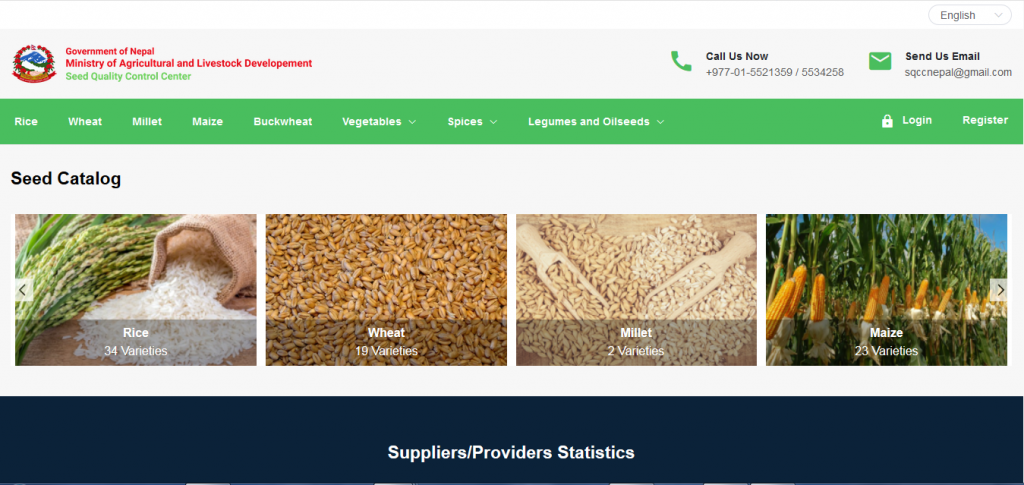

Indigenous peoples in the Highlands have been using a traditional agricultural production system called milpa for thousands of years. The milpa system involves growing maize together with climbing beans, squash, and other crops on a small plot of land. The maize plants support the growth of the climbing beans; the beans enrich soil through biological nitrogen fixation; and squash and other crops protect the soil from erosion, retain water, and prevent weeds.

However, frequent crop failures, declining farm sizes, and other factors result in low household production, forcing families to turn to non-agricultural sources of income or assistance from a family member working abroad. Studies have shown that as household income declines, dietary diversity decreases, which exacerbates undernutrition.

In prior decades, technical assistance for agriculture in Central America focused on larger farms and non-traditional export crops. The researchers recommend inclusion of indigenous communities to enhance milpa systems. Nutrition and employment options can be improved by increasing crop diversity and adopting improved seed varieties that are adapted to the needs of the local communities. This approach requires investments that recognize and advance ancestral knowledge and the role of indigenous women in milpa systems. The Nature Sustainability commentary highlights that technical assistance needs to include women and youth and should increase resilience in production systems to climate change, related weather events, pests, and disease.

“Improving linkages among local farmers, extensionists, students, and researchers is critical to identify and implement opportunities that result in more sustainable agricultural landscapes,” said Keith Kline, senior researcher at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. “For example, improved bean varieties have been developed that provide high-yields and disease resistance, but if they grow too aggressively, they choke out other milpa crops. And successful adoption of improved varieties also depends on whether flavor and texture meet local preferences.”

Strengthening institutions to improve agricultural development, health care, security, education can help create stronger livelihoods and provide the Western Highlands community with a foundation for healthier families and economic stability. As more reliable options become available to feed one’s family, fewer Guatemalans will feel pressured to leave home.

PUBLICATION:

“Enhance indigenous agricultural systems to reduce migration”

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

Santiago Lopez-Ridaura, Senior Scientist, CIMMYT

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT THE MEDIA TEAM:

Rodrigo Ordóñez, Communications Manager, CIMMYT.

r.ordonez@cgiar.org, +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1167.

Ricardo Curiel, Communications Officer, CIMMYT.

r.curiel@cgiar.org, +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1144.

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.