CIMMYT and partners set the pace in maize and wheat research in Africa

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) – The recent inauguration of a new seed storage cold room at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) research center at Kiboko in Makueni County, about 155 kilometers from the capital, adds to the top notch research establishments managed by the national partners in Africa together with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). This successful partnership continues to help farmers overcome crippling challenges in farming and to realize the yield potential of improved varieties.

Since its establishment in Africa, over 40 years ago, CIMMYT has prioritized high quality research work in state-of-the-art research facilities developed through long-standing partnerships with national research organizations, such as KALRO.

“If CIMMYT were to be established today, it would be headquartered in Africa because this is where smallholder farmers face the biggest challenges. At the same time, this is the place where outstanding work is being done to help the farmers rise above the challenges, and with great success,” said Martin Kropff, CIMMYT Director General during his recent visit to Kenya.

The cold room jointly inaugurated by Kropff, and KALRO Director General, Eliud Kireger will help store high value maize seeds with an array of traits including resilience to diseases, insect-pests and climatic stresses as drought and heat, for up to 10 years, without the need for seed regeneration every year, thereby avoiding risk of contamination and use of scarce resources. It will also help make seed readily available for distribution to national partners and seed companies to reach the farmers much faster.

Kireger conveyed his appreciation for the cold room and other research facilities established on KALRO sites, terming these achievements as “rewarding not just to KALRO and to the seed companies, but to many smallholders in Africa, who continue to be the inspiration behind every effort put into maize research and development work by KALRO and partners like CIMMYT.”

In addition to the seed storage cold room, Africa hosts the maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease screening facility in sub-Saharan Africa. The MLN screening facility was established in 2013 at KALRO Naivasha Center in Kenya in response to the outbreak of the devastating MLN disease in eastern Africa. The facility since then has supported both the private and public institutions to screen maize germplasm for MLN under artificial inoculation and in identifying MLN tolerant/resistant lines and hybrids.

• Over 60,000 entries have been tested at the MLN screening site in Naivasha, Kenya since 2013.

• 16 private and public institutions including seed companies and national research organizations have screened their germplasm for MLN. Photo: K. Kaimenyi/CIMMYT

“The MLN screening facility (also a quarantine site) has been supporting the national partners in sub-Saharan Africa, key multinational, local and regional seed companies and CGIAR centers. This facility has become a major resource in the fight against MLN regionally,” added B.M. Prasanna, Director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program as well as the CGIAR Research Program MAIZE. “Tremendous progress has been made through this facility in the last three years. Several promising maize lines with tolerance and resistance to MLN have been identified, and used in breeding programs to develop improved maize hybrids. Already five MLN-tolerant hybrids have been released and now being scaled-up by seed companies for reaching the MLN-affected farmers in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. As many as 22 MLN-tolerant and resistant hybrids are presently undergoing national performance trials in east Africa,” remarked Prasanna.

Another major focus of CIMMYT and partners in the region is to prevent the spread of MLN from the endemic to non-endemic countries in Africa. “This is a strong message to convey that we not only work hard to develop MLN resistant maize varieties for the farmers, but we are also very keen to control the spread of the disease” remarked Kropff during a visit to the site.

In Zimbabwe, an MLN quarantine facility has been established in 2016, in collaboration with the government. This facility is key for safe transfer of research materials, including those with MLN resistance into the currently MLN non-endemic countries in southern Africa, before they get to the partners.

In order to keep up with the emerging stresses and to accelerate development of improved maize varieties, the maize Doubled-Haploid (DH) facility was established in 2013 by CIMMYT and KALRO at the KALRO research center in Kiboko. This facility helps the breeders to significantly shorten the process of developing maize parental lines from 7–8 seasons (using conventional breeding) to just 2–3 seasons.

“Through the facility at Kiboko, we have been able to develop over 60,000 DH lines in 2015 from diverse genetic backgrounds. The DH facility also supports the national agricultural research organisations and small and medium enterprise partners in sub-Saharan Africa to fast-track their breeding work through DH lines,” said Prasanna.

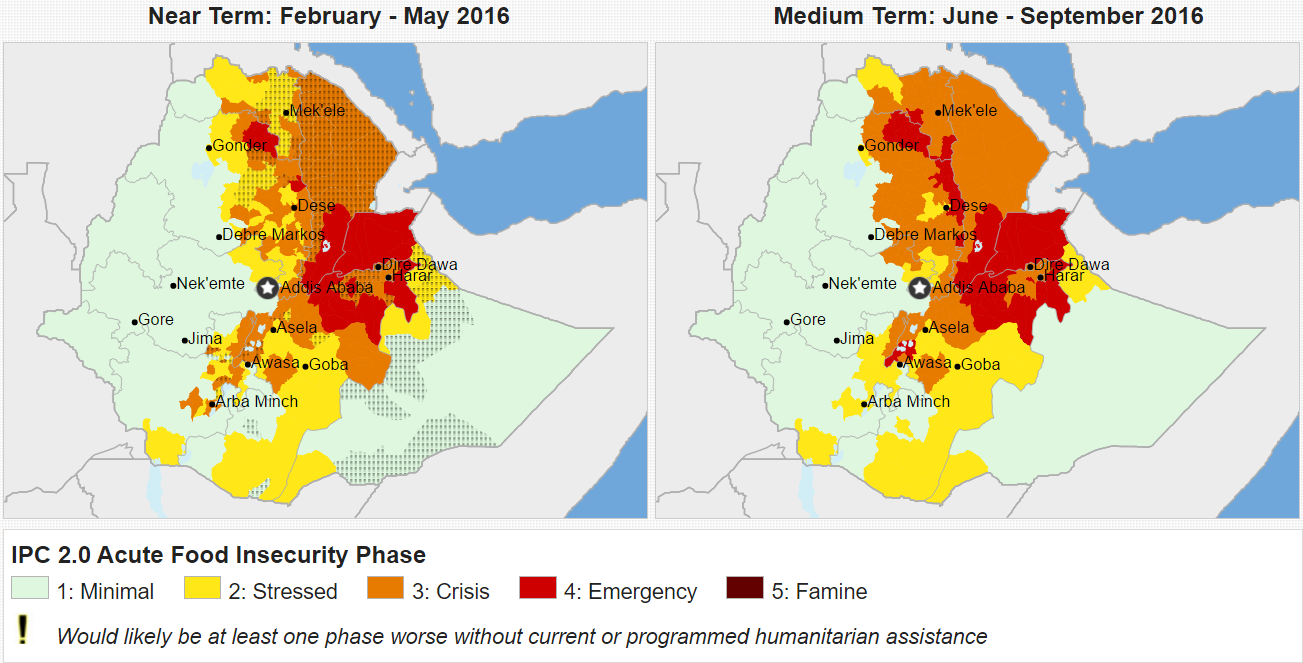

For wheat research-for-development work in Africa, the largest stem rust phenotyping platform in the world sits at KALRO research center in Njoro, Kenya. The facility screens at least 50,000 wheat accessions annually from 20-25 countries. Following the emergence of the Ug99 wheat rust disease pathogen strain in Uganda, the disease spread to 13 countries in Africa. Close to 65 wheat varieties that are resistant to Ug99 stem rust disease have been released globally as a result of the shuttle breeding that includes selection from the screening site at KALRO Njoro.

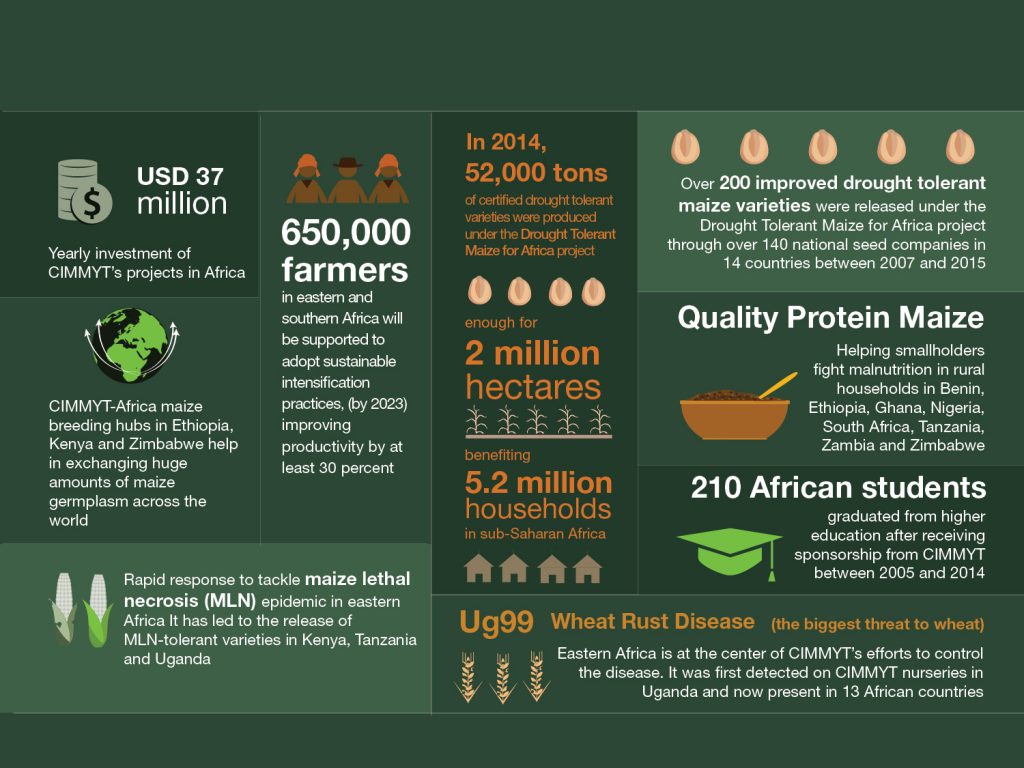

“CIMMYT’s yearly investment of USD 37 million in Africa through various projects has translated into a success story because of the strong collaboration with our partners across Africa,” said Stephen Mugo, CIMMYT’s Regional Representative for Africa. He further added that “research work in Africa is not yet done. No institution, including CIMMYT, cannot do this important work alone. We need to, and will, keep on working together with partners to improve the livelihoods of the African smallholders.”

Key funders of CIMMYT work in Africa include, the USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Sygenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, Australian Centre for International Research, CGIAR Research Program on Maize, Foreign Affairs Trade and Development Canada.