Nepal launches digital soil map

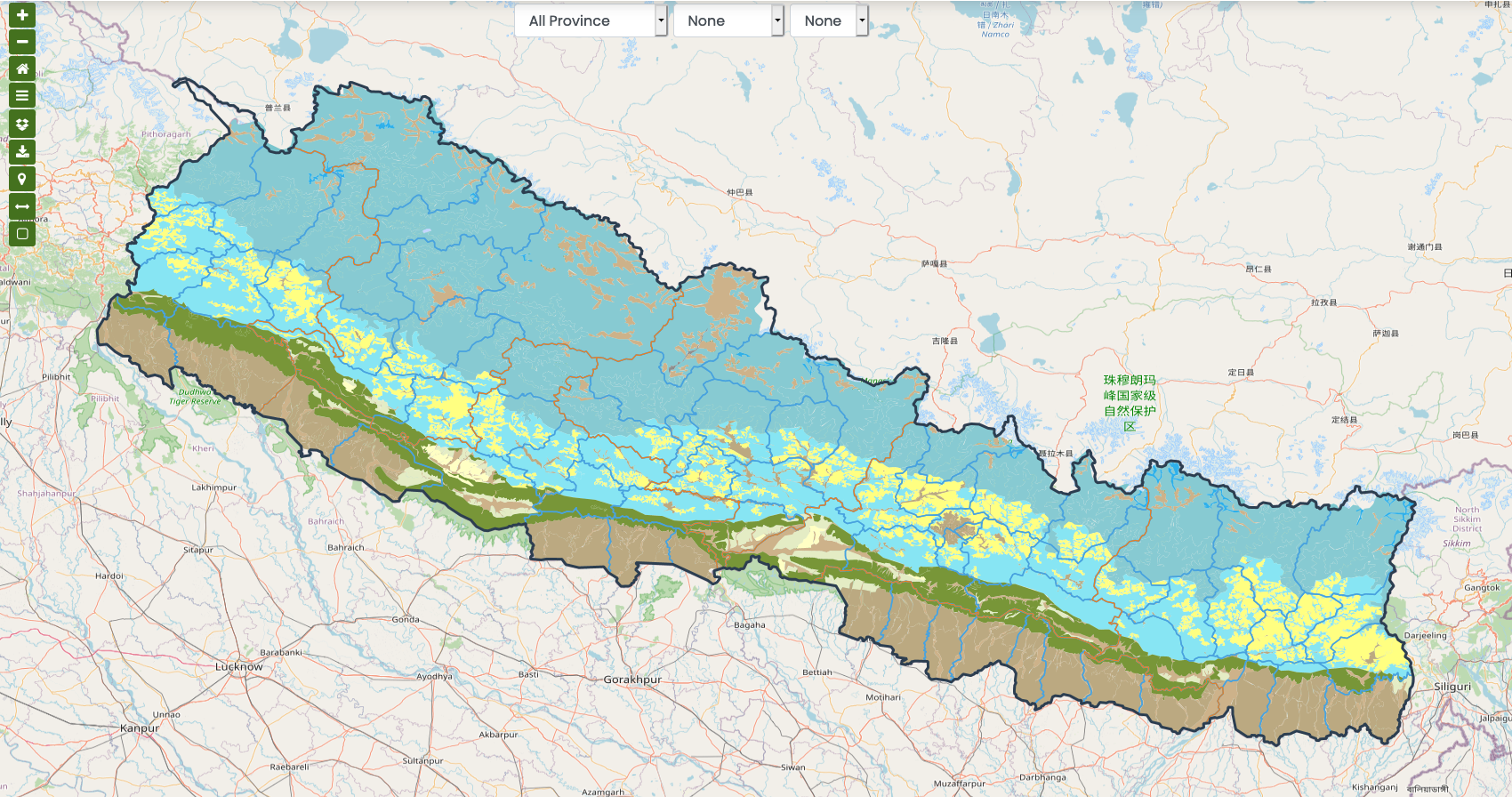

A new digital soil map for Nepal provides access to location-specific information on soil properties for any province, district, municipality or a particular area of interest. The interactive map provides information that will be useful to make new crop- and site-specific fertilizer recommendations for the country.

Produced by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), in collaboration with Nepal Agricultural Research Council’s (NARC) National Soil Science Research Center (NSSRC), this is the first publicly available soil map in South Asia that covers the entire country.

The Prime Minister of Nepal, K.P. Sharma Oli, officially launched the digital soil map at an event on February 24, 2021. Oli highlighted the benefits the map would bring to support soil fertility management in the digital era in Nepal. He emphasized its sustainability and intended use, mainly by farmers.

CIMMYT and NSSRC made a live demonstration of the digital soil map. They also developed and distributed an informative booklet that gives an overview of the map’s major features, operation guidelines, benefits, management and long-term plans.

The launch event was led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development and organized in coordination with NARC, as part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, implemented by CIMMYT. More than 200 people participated in the event, including government officials, policymakers, scientists, professors, development partner representatives, private sector partners and journalists. The event was also livestreamed.

Better decisions

Immediately after the launch of the digital soil map, its CPU usage grew up to 94%. Two days after the launch, 64 new accounts had been created, who downloaded different soil properties data in raster format for use in maps and models.

The new online resource was prepared using soil information from 23,273 soil samples collected from the National Land Use Project, Central Agricultural Laboratory and Nepal Agricultural Research Council. The samples were collected from 56 districts covering seven provinces. These soil properties were combined with environmental covariates (soil forming factors) derived from satellite data and spatial predictions of soil properties were generated using advanced machine learning tools and methods.

The platform is hosted and managed by NARC, who will update the database periodically to ensure its effective management, accuracy and use by local government and relevant stakeholders. The first version of the map was finalized and validated through a workshop organized by NSSRC among different stakeholders, including retired soil scientists and university professors.

“The ministry can use the map to make more efficient management decisions on import, distribution and recommendation of appropriate fertilizer types, including blended fertilizers. The same information will also support provincial governments to select suitable crops and design extension programs for improving soil health,” said Padma Kumari Aryal, Minister of Agriculture and Livestock Development, who chaired the event. “The private sector can utilize the acquired soil information to build interactive and user-friendly mobile apps that can provide soil properties and fertilizer-related information to farmers as part of commercial agri-advisory extension services,” she said.

“These soil maps will not only help to increase crop yields, but also the nutritional value of these crops, which in return will help solve problems of public health such as zinc deficiency in Nepal’s population,” explained Ivan Ortiz-Monasterio, principal scientist at CIMMYT, in a video message.

Yogendra Kumar Karki, secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, presented the program objectives and Deepak Bhandari, executive director of NARC, talked about the implementation of the map and its sustainability. Special remarks were also delivered by USAID Nepal’s mission director, the secretary of Livestock, scientists and professors from Tribhuwan University, the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC) and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

Benefits of digital soil mapping

Soil properties affect crop yield and production. In Nepal, access to soil testing facilities is rather scarce, making it difficult for farmers to know the fertilizer requirement of their land. The absence of a well-developed soil information system and soil fertility maps has been lacking for decades, leading to inadequate strategies for soil fertility and fertilizer management to improve crop productivity. Similarly, existing blanket-type fertilizer recommendations lead to imbalanced application of plant nutrients and fertilizers by farmers, which also negatively affects crop productivity and soil health.

This is where digital soil mapping comes in handy. It allows users to identify a domain with similar soil properties and soil fertility status. The digital platform provides access to domain-specific information on soil properties including soil texture, soil pH, organic matter, nitrogen, available phosphorus and potassium, and micronutrients such as zinc and boron across Nepal’s arable land.

Farmers and extension agents will be able to estimate the total amount of fertilizer required for a particular domain or season. As a decision-support tool, policy makers and provincial government can design and implement programs for improving soil fertility and increasing crop productivity. The map also allows users to identify areas with deficient plant nutrients and provide site-specific fertilizer formulations; for example, determining the right type of blended fertilizers required for balanced fertilization programs. Academics can also obtain periodic updates from these soil maps and use it as a resource while teaching their students.

As digital soil mapping advances, NSSRC will work towards institutionalizing the platform, building awareness at the province and local levels, validating the map, and establishing a national soil information system for the country.

Nepal’s digital soil map is readily accessible on the NSSRC web portal:

https://soil.narc.gov.np/soil/soilmap/

Global thought leader, philanthropist and one of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and CGIAR’s most vocal and generous supporters, Bill Gates, wrote a book about climate change and is now taking it around the world on a virtual book tour to share a message of urgency and hope.

Global thought leader, philanthropist and one of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and CGIAR’s most vocal and generous supporters, Bill Gates, wrote a book about climate change and is now taking it around the world on a virtual book tour to share a message of urgency and hope.