Ethiopian machines for Ethiopian farmers

In many sub-Saharan countries, including Ethiopia, smallholder farmers of legume, wheat, and maize struggle to maintain their own food security, produce higher incomes, and promote economic growth and jobs in agricultural communities.

As farmers, fabricators, and aid workers collaborate to move forward on this problem, innovative solutions are moving out into the field – and generating new ideas across the continent.

Where are machines for small farmers?

Machines tailored to local needs and conditions can often make a big difference–but most agricultural technology is designed and produced to meet the requirements of massive, commercial farms. To help close this gap, Green Innovations Centers (GIC) work to connect smallholding farmers with locally produced technology that can transform their business, their family lives, and their local economies.

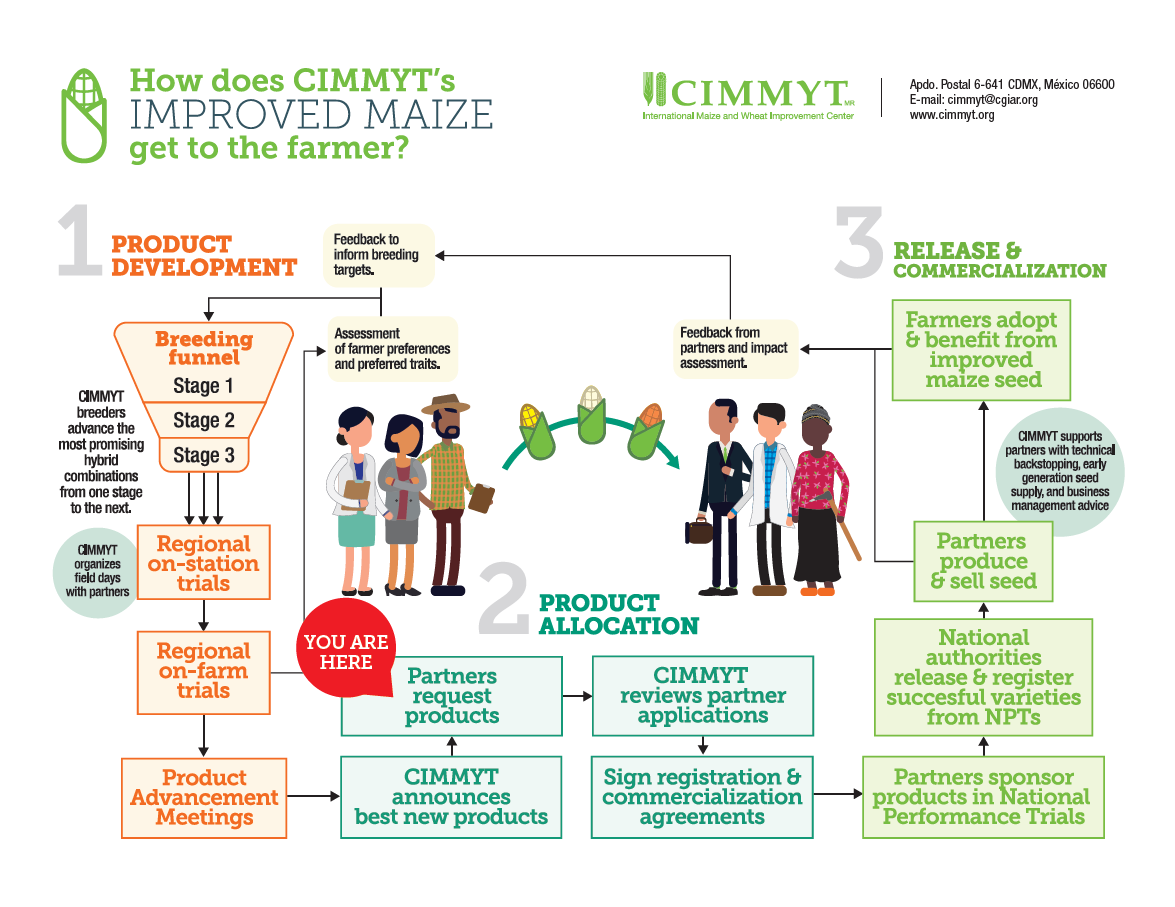

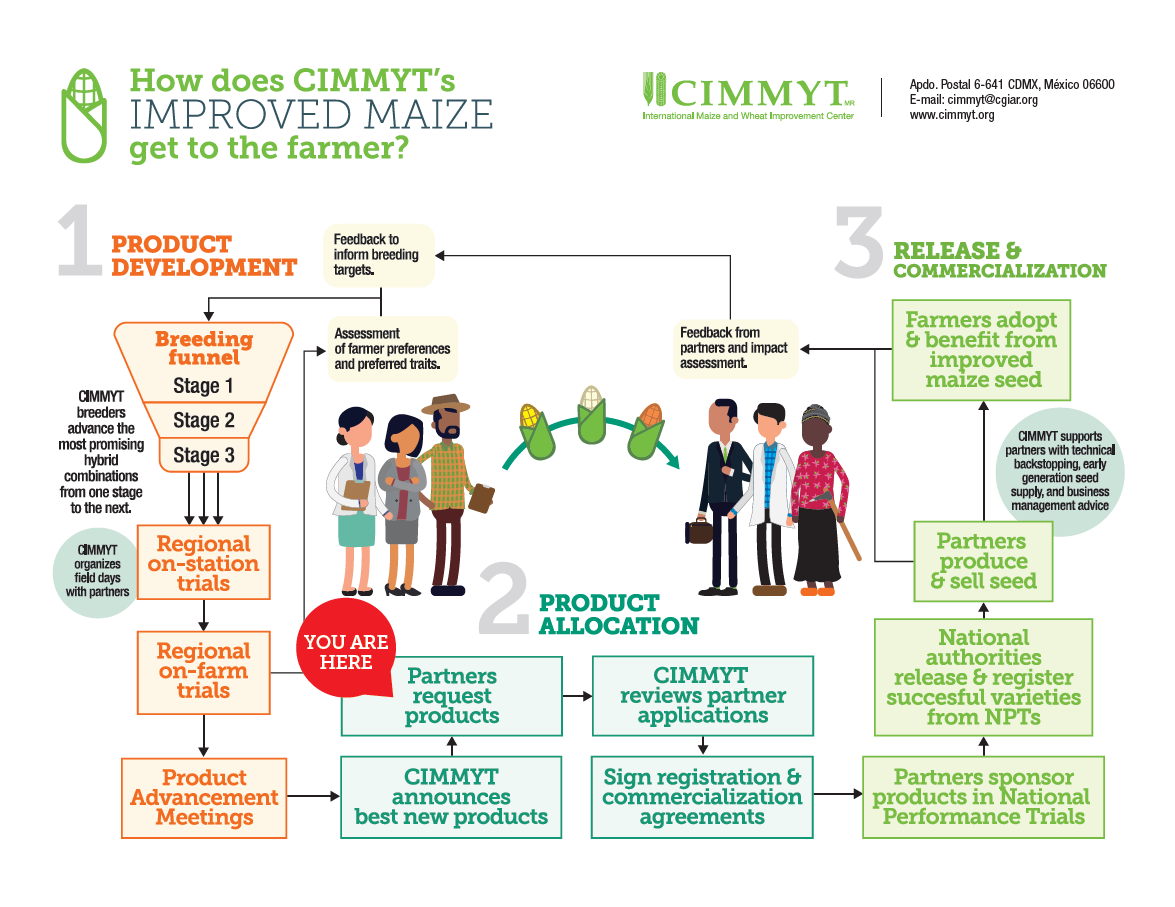

Launched in 2014 by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development’s special initiative, ONE WORLD No Hunger, the GIC collaborate with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) to increase agricultural mechanization in 14 countries in Africa and two in Asia.

The need for seed

Informal seed systems, in which farmers save and reuse seed, and exchange low quality seed with other farmers, are prevalent among Ethiopian smallholder farmers. Seed cleaning plays an important role in helping farmers build high-yielding seed development systems by removing seed pods and other chaff, eliminating seeds that are too small or infected, and refining the seeds to a high-quality remainder.

After GIC staff in Ethiopia identified seed cleaning as a critical need for smallholding farmers in the country, researchers set out to develop a solution that was affordable, sustainable, and adaptable to local demands.

Local machines for local farmers

In 2022, GIC Ethiopia partnered with Techno-Nejat Industries in Adama, Ethiopia, to design and produce a first run of mobile seed cleaners for use by smallholding farmers across the country. Techno-Nejat has an established track record in agricultural fabrication and was eager to take on the new collaboration.

In early March, the company completed the initial delivery of eight seed cleaners. The machines process chickpea, soy, wheat, and barley seed with a maximum capacity of 1.5 tons per hour. With wheels and a compact, efficient design, they are also easy to move from one farmer’s property to another. At a cost of US $7,500 and a production time of 55 days, the machines have potential both for expansion within Ethiopia and scaling up for export.

Seeding future collaboration

Smallholding farmer cooperatives will take delivery of the first eight seed cleaners in the coming weeks. And while Ethiopian farmers are ready to experience the immediate benefits for their operations, this innovation is also showing promise for additional collaboration.

“Through existing GIC networks, we have connected with Techno Agro Industrie, a company manufacturing seed cleaners in Benin,” said Techno-Nejat’s owner Usman Abdella. “We welcome partnership opportunities, and we extend the red carpet,” Usman said.

As funding for GIC’s mechanization effort winds down, this organic, private Ethiopia-Benin partnership holds promise to generate continued benefits of innovation after the project has concluded, fostering South-South collaboration within Africa.