Book celebrates maize “secret scientists” on International Day of Rural Women

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – Rural women play a critical role in enhancing agricultural and rural development, improving food security and eradicating rural poverty.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – Rural women play a critical role in enhancing agricultural and rural development, improving food security and eradicating rural poverty.

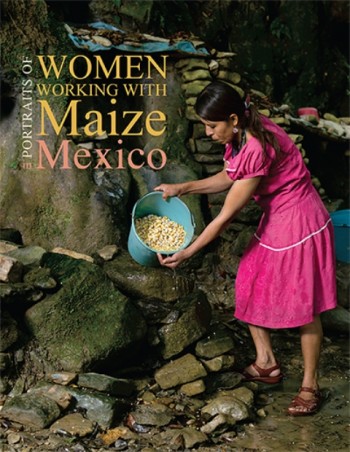

Women provide innumerable benefits to agricultural systems around the world at all levels of the value chain, but their contributions often go unrecognized. This year, for the U.N. International Day of Rural Women (IDRW) on October 15, the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE) would like to honor the significant contributions that women make to agriculture around the world by sharing photos and stories via our social media channels from our new book: “Portraits of Women Working with Maize in Mexico.”

The book seeks to shine light on the often unseen contributions that rural women make to their families, communities, countries and the world through agriculture.

“As part of its emphasis on contributing to gender equality and equity in agricultural research for development, MAIZE has increased investments to expand the evidence base on how gender norms and relations intertwine with agricultural practices and innovation and the implications of this for agricultural research and development,” said Lone Badstue, CIMMYT strategic leader for gender research, who also works on the MAIZE CRP, which is administered by the CGIAR consortium of agricultural research.

“This documentary initiative expands these efforts, portraying an often overlooked side of maize-based livelihoods in Mexico, through images and testimonies of different women, who describe in their own words, their lives as farmers, food makers, artisans and vendors.”

The goal of assuring the food security and livelihoods of rural women is at the heart of many of MAIZE’s projects and activities.

The cross-CRP gender study “GENNOVATE” launchedin 2014 promises to integrate gender-sensitive approaches across MAIZE work in order to better serve rural women as theyadopt agricultural technology.

In 2014, MAIZE also implemented the “Gender Matters in Farm Power” project, led by the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), which is investigating opportunities to empower men and women through scale-appropriate mechanization. Other activities included efforts to integrate gender into participatory varietal section, the creation of a gender strategy for maize seed system development and initiatives to integrate gender into advisory services and small-scale entrepreneurship.

The participation of rural women is crucial to the success of the MAIZE CRP.

Their faith in using our new varieties and implementing the agricultural practices recommended by MAIZE makes them beacons in their communities, operating as “secret scientists.” They complete hands-on, on-the-ground research for MAIZE, experimenting to determine the viability of products and practices to their neighbors and paving the way for smallholder farmers worldwide to successfully use and benefit from them.

Their feedback is essential, as we cannot achieve our goal of sustainably increasing production for the 900 million poor consumers for whom maize is a staple food without first closing the gender gap in agriculture.

According to the U.N Food and Agriculture Organization, if women in agriculture were afforded the same rights and opportunities as men, they could increase their farm yields by an estimated 20 to 30 percent and feed up to 150 million more people worldwide. This makes rural women some of our greatest partners in the fight to eradicate hunger and poverty.

We invite you to share your own photos and stories of rural women with us this week using the hashtag #IDRW, to contribute to a global conversation on the world’s “secret scientists”—recognizing our “behind the scenes” partners who are so crucial to the success of our research and projects and work every day to protect and promote global food security—rural women.

BOOK: Portraits of Women Working with Maize in Mexico

http://repository.cimmyt.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10883/4478/57042.pdf?sequence=1

Video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nc0opvkPoh4

CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff speaks on the topic of ‘Wheat and the role of gender in the developing world’ prior to the 2015 Women in Triticum Awards at the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative Workshop in Sydney on 19 September.

CIMMYT Director General Martin Kropff speaks on the topic of ‘Wheat and the role of gender in the developing world’ prior to the 2015 Women in Triticum Awards at the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative Workshop in Sydney on 19 September.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Amanda Niode writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Asriani Anie Annisa Hasan of the Gorontalo Corn Information Center and Food Security Agency.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Amanda Niode writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Asriani Anie Annisa Hasan of the Gorontalo Corn Information Center and Food Security Agency.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Haley Kirk writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Jennifer Brito, food security coordinator at

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, Haley Kirk writes about her Super Woman of Maize, Jennifer Brito, food security coordinator at  International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, scientist Velu Govindan writes about his Super Woman of Wheat, Chhavi Tiwari, a senior research associate at Banaras Hindu University.

International Women’s Day on March 8, offers an opportunity to recognize the achievements of women worldwide. This year, CIMMYT asked readers to submit stories about women they admire for their selfless dedication to either maize or wheat. In the following story, scientist Velu Govindan writes about his Super Woman of Wheat, Chhavi Tiwari, a senior research associate at Banaras Hindu University.