Participatory approaches to gender in agricultural development

When designing and implementing agricultural development projects, it is difficult to ensure that they are responsive to gender dynamics. For Mulunesh Tsegaye, a gender specialist attached to two projects working on the areas of nutrition and mechanization in Ethiopia, participatory approaches are the best way forward.

“I have lived and worked with communities. If you want to help a community, they know best how to do things for themselves. There are also issues of sustainability when you are not there forever. You need to make communities own what has been done in an effective participatory approach,” she said.

Including both men and women

The CIMMYT-led Nutritious Maize for Ethiopia (NuME) project uses demonstrations, field days, cooking demonstrations and messaging to encourage farmers to adopt and use improved quality protein maize (QPM) varieties, bred to contain the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan that are usually lacking in maize-based diets. The Ethiopian government adopted a plan to plant QPM on 200,000 hectares by 2015-2017.

NuME’s project staff, and donor Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD), are highly committed to gender-based approaches, meaning that Mulunesh’s initial role was to finalize the gender equality strategy and support implementation with partners.

By involving partners in an action planning workshop, Mulunesh helped them to follow a less technical and more gender-aware approach, for example by taking women’s time constraints into account when organizing events.

This involved introducing some challenging ideas. Due to men’s role as breadwinners and decision-makers in Ethiopian society, Mulunesh suggested inviting men to learn about better nutrition in the household in order to avoid perpetuating stereotypes about the gender division of labor.

“For a project to be gender-sensitive, nutrition education should not focus only on women but also on men to be practical. Of course, there were times when the project’s stakeholders resisted some of my ideas. They even questioned me: ‘How can we even ask men farmers to cook?’”

Now, men are always invited to nutrition education events, and are also presented in educational videos as active partners, even if they are not themselves cooking.

“Nutrition is a community and public health issue,” said Mulunesh. “Public involves both men and women, when you go down to the family level you have both husbands and wives. You cannot talk about nutrition separately from decision-making and access to resources.”

The Farm Power and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification (FACASI) project is involved in researching new technologies that can be used to mechanize farming at smaller scales. Introducing mechanization will likely alter who performs different tasks or ultimately benefits, meaning that a gender-sensitive approach is crucial.

Again, Mulunesh takes the participation perspective. “One of the issues of introducing mechanization is inclusiveness. You need to include women as co-designers from the beginning so that it will be easier for them to participate in their operation.”

“In general, the farmers tell us that almost every agricultural task involves both men and women. Plowing is mostly done by oxen operated by men, but recently, especially where there are female-headed households, women are plowing and it is becoming more acceptable. There are even recent findings from Southern Ethiopia that women may be considered attractive if they plow!”

Women and men are both involved to some extent with land preparation, planting, weeding, harvesting or helping with threshing. However, women do not just help in farming, they also cook, transport the food long distances for the men working in the farm, and also take care of children and cattle.

A study by the Dutch Royal Tropical Institute, Gender Matters in Farm Power, has already drawn some conclusions about gender relations in farm power that are being used as indicators for the gender performance of the mechanization project.

These indicators are important to track how labor activities change with the introduction of mechanization. “My main concern is that in most cases, when a job traditionally considered the role of women gets mechanized, becomes easier or highly paid, it is immediately taken over by men, which would imply a lot in terms of control over assets and income,” said Mulunesh.

-

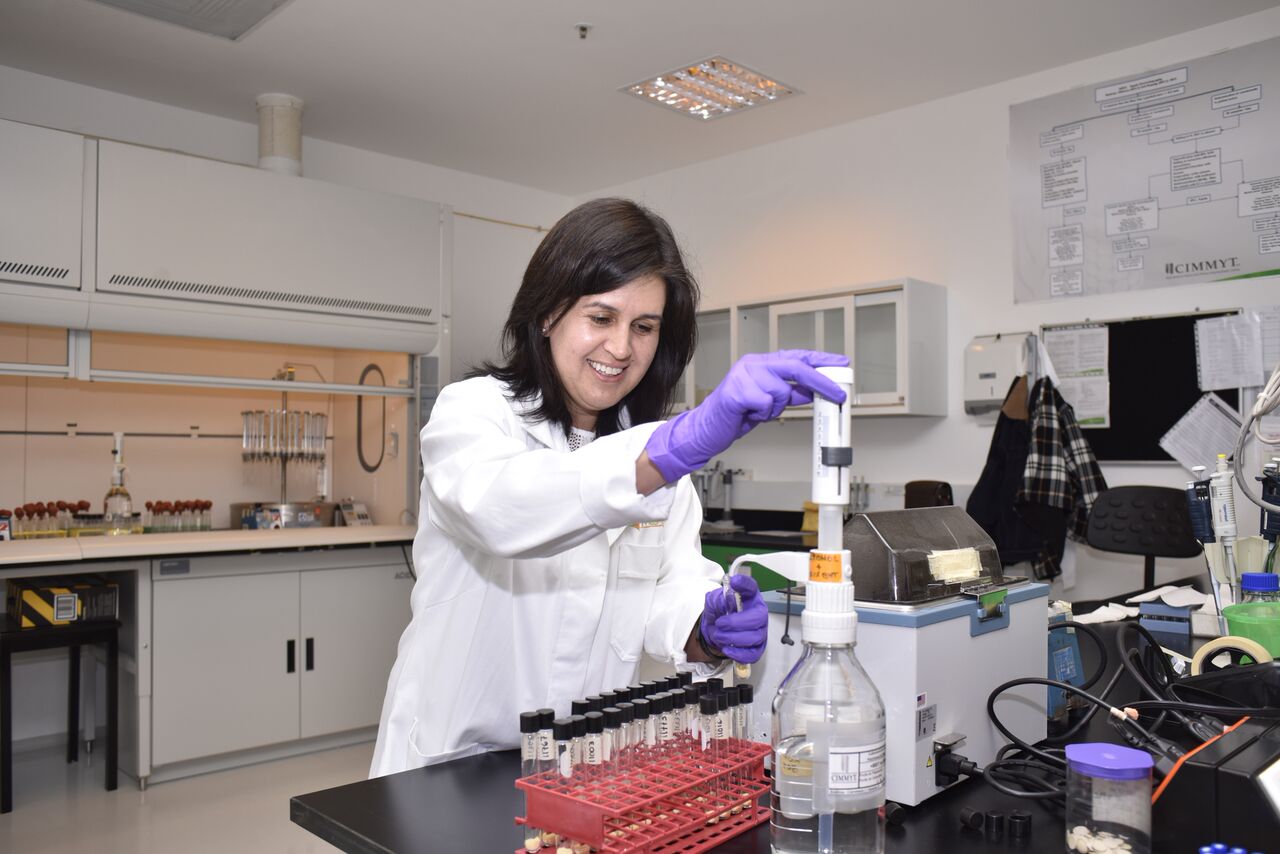

Front row, from left to right: Mulunesh Tsegaye, FACASI gender and agriculture specialist; Katrine Danielsen KIT; Elizabeth Mukewa consultant; Mahlet Mariam, consultant; and David Kahan CIMMYT, business model specialist. Back row, from left to right: Anouka van Eerdewijk KIT; Lone Badstue CIMMYT strategic leader, gender research and mainstreaming; and Frédéric Baudron, FACASI project leader. Credit: Steffen Schulz/CIMMYT

Community conversations

In order to foster social change and identify the needs of women and vulnerable groups, Mulunesh initiated a community conversation program, based on lines first developed by the United Nations Development Programme. Pilots are ongoing in two districts in the south of Ethiopia; a total of four groups are involved, each of which may include 50-70 participants.

“You need to start piece-by-piece, because there are lots of issues around gender stereotypes, culture and religious issues. It is not that men are not willing to participate; rather it is because they are also victims of the socio-cultural system in place.”

When asked about the situation of women in the community, many people claim that things have already changed; discussions and joint decisions are occurring in the household and women are getting empowered in terms of access to resources. Over the coming year, Mulunesh will compare how information diffuses differently in gender-segregated or gender mixed groups.

FACASI is funded by the Australian International Food Security Research Centre, managed by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research and implemented by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

NuME is funded by DFATD and managed by CIMMYT in collaboration with Ethiopian research institutions, international non-governmental organizations, universities and public and private seed companies in Ethiopia.

Jennifer Johnson

Jennifer Johnson