New publications: From working in the fields to taking control

Using data from 12 communities across four Indian states, an international team of researchers has shed new light on how women are gradually innovating and influencing decision-making in wheat-based systems.

The study, published this month in The European Journal of Development Research, challenges stereotypes of men being the sole decision-makers in wheat-based systems and performing all the work. The authors, which include researchers from the CGIAR Research Program on Wheat (WHEAT)-funded GENNOVATE initiative, show that women adopt specific strategies to further their interests in the context of wheat-based livelihoods.

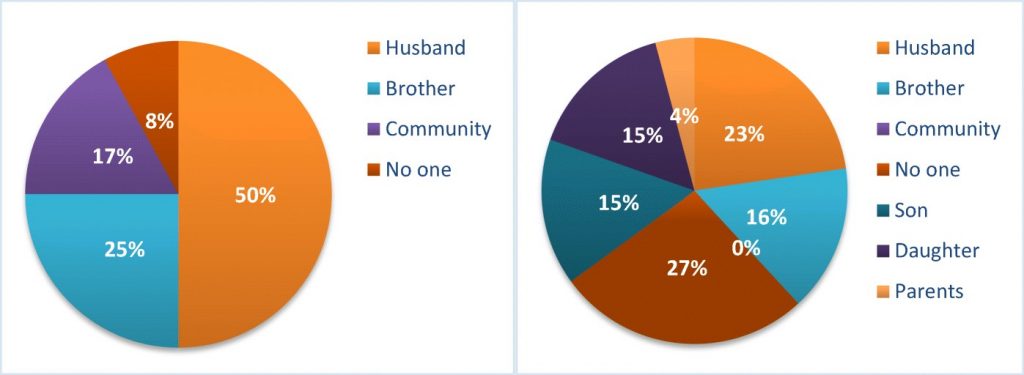

In parts of India, agriculture has become increasingly feminized in response to rising migration of men from rural areas to cities. An increasing proportion of women, relative to men, are working in the fields. However, little is known about whether these women are actually taking key decisions.

The authors distinguish between high gender gap communities — identified as economically vibrant and highly male-dominant — and low gender gap communities, which are also economically vibrant but where women have a stronger say and more room to maneuver.

The study highlights six strategies women adopt to participate actively in decision-making. These range from less openly challenging strategies that the authors term acquiescence, murmuring, and quiet co-performance (typical of high gender gap communities), to more assertive ones like active consultation, women managing, and finally, women deciding (low gender gap communities).

In acquiescence, for example, women are fully conscious that men do not expect them to take part in agricultural decision-making, but do not articulate any overt forms of resistance.

In quiet co-performance, some middle-income women in high gender gap communities begin to quietly support men’s ability to innovate, for example by helping to finance the innovation, and through carefully nuanced ‘suggestions’ or ‘advice.’ They don’t openly question that men take decisions in wheat production. Rather, they appear to use male agency to support their personal and household level goals.

In the final strategy, women take all decisions in relation to farming and innovation. Their husbands recognize this process is happening and support it.

“One important factor in stronger women’s decision-making capacity is male outmigration. This is a reality in several of the low gender gap villages studied—and it is a reality in many other communities in India. Another is education—many women and their daughters talked about how empowering this is,” said gender researcher and lead-author Cathy Farnworth.

In some communities, the study shows, women and men are adapting by promoting women’s “managerial” decision-making. However, the study also shows that in most locations the extension services have failed to recognize the new reality of male absence and women decision-makers. This seriously hampers women, and is restricting agricultural progress.

Progressive village heads are critical to progress, too. In some communities, they are inclusive of women but in others, they marginalize women. Input suppliers — including machinery providers — also have a vested interest in supporting women farm managers. Unsurprisingly, without the support of extension services, village heads, and other important local actors, women’s ability to take effective decisions is reduced.

“The co-authors, partners at Glasgow Caledonian University and in India, were very important to both obtaining the fieldwork data, and the development of the typology” said Lone Badstue, researcher at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and another co-author of the paper.

The new typology will allow researchers and development partners to better understand empowerment dynamics and women’s agency in agriculture. The authors argue that development partners should support these strategies but must ultimately leave them in the hands of women themselves to manage.

“It’s an exciting study because the typology can be used by anyone to distinguish between the ways women (and men) express their ideas and get to where they want”, concluded Farnworth.

Read the full article in The European Journal of Development Research:

From Working in the Fields to Taking Control. Towards a Typology of Women’s Decision-Making in Wheat in India

See more recent publications from CIMMYT researchers:

- isqg: A Binary Framework for in Silico Quantitative Genetics. 2019. Toledo, F.H., Perez-Rodriguez, P., Crossa, J., Burgueño, J. In: G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics v. 9, no. 8, pag. 2425-2428

- Short-term impacts of conservation agriculture on soil physical properties and productivity in the midhills of Nepal. 2019. Laborde, J.P., Wortmann, C.S., Blanco-Canqui, H., McDonald, A., Baigorria, G.A., Lindquist, J.L. In: Agronomy Journal v.111, no. 4, pag. 2128-2139.

- Meloidogyne arenaria attacking eggplant in Souss region, Morocco. 2019. Mokrini, F., El Aimani, A., Abdellah Houari, Bouharroud, R., Ahmed Wifaya, Dababat, A.A. In: Australasian Plant Disease Notes v. 14, no. 1, art. 30.

- Differences in women’s and men’s conservation of cacao agroforests in coastal Ecuador. 2019. Blare, T., Useche, P. In: Environmental Conservation v. 46, no. 4, pag. 302-309.

- Assessment of the individual and combined effects of Rht8 and Ppd-D1a on plant height, time to heading and yield traits in common wheat. 2019. Kunpu Zhang, Junjun Wang, Huanju Qin, Zhiying Wei, Libo Hang, Pengwei Zhang, Reynolds, M.P., Daowen Wang In: The Crop Journal v. 7, no. 6, pag. 845-856.

- Quantifying carbon for agricultural soil management: from the current status toward a global soil information system. 2019. Paustian, K., Collier, S., Baldock, J., Burgess, R., Creque, J., DeLonge, M., Dungait, J., Ellert, B., Frank, S., Goddard, T., Govaerts, B., Grundy, M., Henning, M., Izaurralde, R.C., Madaras, M., McConkey, B., Porzig, E., Rice, C., Searle, R., Seavy, N., Skalsky, R., Mulhern, W., Jahn, M. In: Carbon Management v. 10, no. 6, pag. 567-587.

- Factors contributing to maize and bean yield gaps in Central America vary with site and agroecological conditions. 2019. Eash, L., Fonte, S.J., Sonder, K., Honsdorf, N., Schmidt, A., Govaerts, B., Verhulst, N. In: Journal of Agricultural Science v. 157, no. 4, pag. 300-317.

- Genome editing, gene drives, and synthetic biology: will they contribute to disease-resistance crops, and who will benefit?. 2019. Pixley, K.V., Falck-Zepeda, J.B., Giller, K.E., Glenna, L.L., Gould, F., Mallory-Smith, C., Stelly, D.M., Stewart Jr, C.N. In: Annual Review of Phytopathology v. 57, pag. 165-188.

- Rice mealybug (Brevennia rehi): a potential threat to rice in a long-term rice-based conservation agriculture system in the middle Indo-Gangetic Plain. 2019. Mishra, J. S., Poonia, S. P., Choudhary, J.S., Kumar, R., Monobrullah, M., Verma, M., Malik, R.K., Bhatt, B. P. In: Current Science v. 117, no. 4, 566-568.

- Trends in key soil parameters under conservation agriculture-based sustainable intensification farming practices in the Eastern Ganga Alluvial Plains. 2019. Sinha, A.K., Ghosh, A., Dhar, T., Bhattacharya, P.M., Mitra, B., Rakesh, S., Paneru, P., Shrestha, R., Manandhar, S., Beura, K., Dutta, S.K., Pradhan, A.K., Rao, K.K., Hossain, A., Siddquie, N., Molla, M.S.H., Chaki, A.K., Gathala, M.K., Saiful Islam., Dalal, R.C., Gaydon, D.S., Laing, A.M., Menzies, N.W. In: Soil Research v. 57, no. 8, Pag. 883-893.

- Genetic contribution of synthetic hexaploid wheat to CIMMYT’s spring bread wheat breeding germplasm. 2019. Rosyara, U., Kishii, M., Payne, T.S., Sansaloni, C.P., Singh, R.P., Braun, HJ., Dreisigacker, S. In: Nature Scientific Reports v. 9, no. 1, art. 12355.

- Joint use of genome, pedigree, and their interaction with environment for predicting the performance of wheat lines in new environments. 2019. Howard, R., Gianola, D., Montesinos-Lopez, O.A., Juliana, P., Singh, R.P., Poland, J.A., Shrestha, S., Perez-Rodriguez, P., Crossa, J., Jarquín, D. In: G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics v. 9, no. 9 pag. 2925-2934.

- Deep kernel for genomic and near infrared predictions in multi-environment breeding trials. 2019. Cuevas, J., Montesinos-Lopez, O.A., Juliana, P., Guzman, C., Perez-Rodriguez, P., González-Bucio, J., Burgueño, J., Montesinos-Lopez, A., Crossa, J. In: G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics v. 9. No. 9, pag. 2913-2924.

- Multi-environment QTL analysis using an updated genetic map of a widely distributed Seri × Babax spring wheat population. 2019. Caiyun Liu, Khodaee, M., Lopes, M.S., Sansaloni, C.P., Dreisigacker, S., Sukumaran, S., Reynolds, M.P. In: Molecular Breeding v. 39, no. 9, art. 134.

- Characterization of Ethiopian wheat germplasm for resistance to four Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici races facilitated by single-race nurseries. 2019. Hundie, B., Girma, B., Tadesse, Z., Edae, E., Olivera, P., Hailu, E., Worku Denbel Bulbula, Abeyo Bekele Geleta, Badebo, A., Cisar, G., Brown-Guedira, G., Gale, S., Yue Jin, Rouse, M.N. In: Plant Disease v. 103, no. 9, pag. 2359-2366.

- Marker assisted transfer of stripe rust and stem rust resistance genes into four wheat cultivars. 2019. Randhawa, M.S., Bains, N., Sohu, V.S., Chhuneja Parveen, Trethowan, R.M., Bariana, H.S., Bansal, U. In: Agronomy v. 9, no. 9, art. 497.

- Design and experiment of anti-vibrating and anti-wrapping rotary components for subsoiler cum rotary tiller. 2019. Kan Zheng, McHugh, A., Hongwen Li, Qingjie Wang, Caiyun Lu, Hongnan Hu, Wenzheng Liu, Zhiqiang Zhang, Peng Liu, Jin He In: International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering v. 14, no. 4, pag. 47-55.

- Hydrogen peroxide prompted lignification affects pathogenicity of hemi-bio-trophic pathogen Bipolaris sorokiniana to wheat. 2019. Poudel, A., Sudhir Navathe, Chand, R., Vinod Kumar Mishra, Singh, P.K., Joshi, A.K. In: Plant Pathology Journal v. 35, no. 4, pag. 287-300.

- Population-dependent reproducible deviation from natural bread wheat genome in synthetic hexaploid wheat. 2019. Jighly, A., Joukhadar, R., Sehgal, D., Sukhwinder-Singh, Ogbonnaya, F.C., Daetwyler, H.D. In: Plant Journal v. 100, no, 4. Pag. 801-812.

- How do informal farmland rental markets affect smallholders’ well-being? Evidence from a matched tenant–landlord survey in Malawi. 2019. Ricker-Gilbert, J., Chamberlin, J., Kanyamuka, J., Jumbe, C.B.L., Lunduka, R., Kaiyatsa, S. In: Agricultural Economics v. 50, no. 5, pag. 595-613.

- Distribution and diversity of cyst nematode (Nematoda: Heteroderidae) populations in the Republic of Azerbaijan, and their molecular characterization using ITS-rDNA analysis. 2019. Dababat, A.A., Muminjanov, H., Erginbas-Orakci, G., Ahmadova Fakhraddin, G., Waeyenberge, L., Senol Yildiz, Duman, N., Imren, M. In: Nematropica v. 49, no. 1, pag. 18-30.

- Response of IITA maize inbred lines bred for Striga hermonthica resistance to Striga asiatica and associated resistance mechanisms in southern Africa. 2019. Gasura, E., Setimela, P.S., Mabasa, S., Rwafa, R., Kageler, S., Nyakurwa, C. S. In: Euphytica v. 215, no. 10, art. 151.

- QTL mapping and transcriptome analysis to identify differentially expressed genes induced by Septoria tritici blotch disease of wheat. 2019. Odilbekov, F., Xinyao He, Armoniené, R., Saripella, G.V., Henriksson, T., Singh, P.K., Chawade, A. In: Agronomy v. 9, no. 9, art. 510.

- Molecular diversity and selective sweeps in maize inbred lines adapted to African highlands. 2019. Dagne Wegary Gissa, Chere, A.T., Prasanna, B.M., Berhanu Tadesse Ertiro, Alachiotis, N., Negera, D., Awas, G., Abakemal, D., Ogugo, V., Gowda, M., Fentaye Kassa Semagn In: Nature Scientific Reports v. 9, art. 13490.

- The impact of salinity on paddy production and possible varietal portfolio transition: a Vietnamese case study. 2019. Dam, T.H.T., Amjath Babu, T.S., Bellingrath-Kimura, S., Zander, P. In: Paddy and Water Environment In: 17. No. 4, pag. 771-782.