Groundwater conservation policies help fuel air pollution crisis in northwestern India, new study finds

Groundwater conservation policies are contributing to the air pollution crisis in northwestern India by concentrating agricultural fires into a narrower window when weather conditions favor poor air quality, according to a new study by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) published on Nature Sustainability.

Facing severe groundwater depletion from intensive crop cultivation, the state governments of Haryana and Punjab introduced separate legislation in 2009 to prohibit early rice establishment in order to reduce water consumption. The study revealed that later rice planting results in later rice harvest, leading to a delayed and condensed period when residues are burned prior to wheat establishment. Consequently, more farmers are setting fire to crop residues at the same time, increasing peak fire intensity by 39%, contributing significantly to atmospheric pollution.

“Despite being illegal, the burning of post-harvest rice residues continues to be the most common practice of crop residue management in northwestern India, and while groundwater policies are helping arrest water depletion, they also appear to be exacerbating one of the most acute public health problems confronting India,” said CIMMYT scientist Balwinder Singh.

“Burning agricultural waste dominantly releases PM2.5 aerosols, a type of fine particulate matter that is particularly harmful to human health,” he explained.

Air pollution in India kills an estimated 1.5 million people every year, with nearly half of these deaths occurring in the Indo-Gangetic Plains, the northernmost part of the country that includes New Delhi.

A holistic view of policies to support sustainable development

The research results shed light on the sustainability challenges confronting many highly productive agricultural systems, where addressing one problem can exacerbate others, said Andrew McDonald, a professor at Cornell University and co-author of the study.

“Identifying and managing tradeoffs and capitalizing on synergies between crop productivity, resource conservation, and environmental quality is essential,” McDonald said.

“To devise more effective agricultural development programs and policies, integrative assessments are required that meld groundwater, air quality, economic, and technology scaling considerations in common frameworks,” he explained.

The current policy environment in India encourages productivity maximization of cereals and very high levels of residue production especially in the western Indo-Gangetic Plains, according to Bruno Gerard, another author of the study and head of CIMMYT’s Sustainable Intensification Program.

“If these policies are changed, companion efforts must facilitate sustainable intensification in areas such as the Eastern Gangetic Plains, where water resources are relatively abundant and closer coupling of crop-livestock systems provides a diverse set of end-uses for crops residues,” Gerard said.

The way forward

Northwestern India is home to millions of smallholder farmers and a global breadbasket for grain staples, accounting for 85% of the wheat procured by the Indian government. Thus, what happens here has regional and global ramifications for food security.

“A sensible approach for overcoming tradeoffs will embrace agronomic technologies such as the Happy Seeder, a seed drill that plants seeds without impacting crop residue, providing farmers the technical means to avoid residue burning,” said ML Jat, a scientist with CIMMYT who coordinates sustainable intensification programs in northwestern India.

“Through continued efforts on the technical refinement and business model development for the Happy Seeder technology, uptake has accelerated,” he added. “Financial incentives in the form of payments for ecosystem services may provide an additional boost to adoption.”

“Additional agronomic management measure such as cultivation of shorter-duration rice varieties may help arrest groundwater decline while reducing the damaging concentration of agricultural burning,” Jat explained.

The researchers suggested that long-term solutions will likely require crop diversification away from rice towards crops that demand less water, like maize, as recently started by the government in the state of Haryana.

Access the journal article on Nature Sustainability:

Tradeoffs between groundwater conservation and air pollution from agricultural fires in northwest India

Read Balwinder Singh’s op-ed in The Telegraph:

Groundwater, the unexpected villain in India’s air pollution crisis

For more information or interview requests, please contact:

Genevieve Renard, Head of Communications, CIMMYT. g.renard@cgiar.org +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 2019.

Rodrigo Ordóñez, Communications Manager, CIMMYT. r.ordonez@cgiar.org +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1167.

ABOUT CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of CGIAR and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat, and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies.

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.

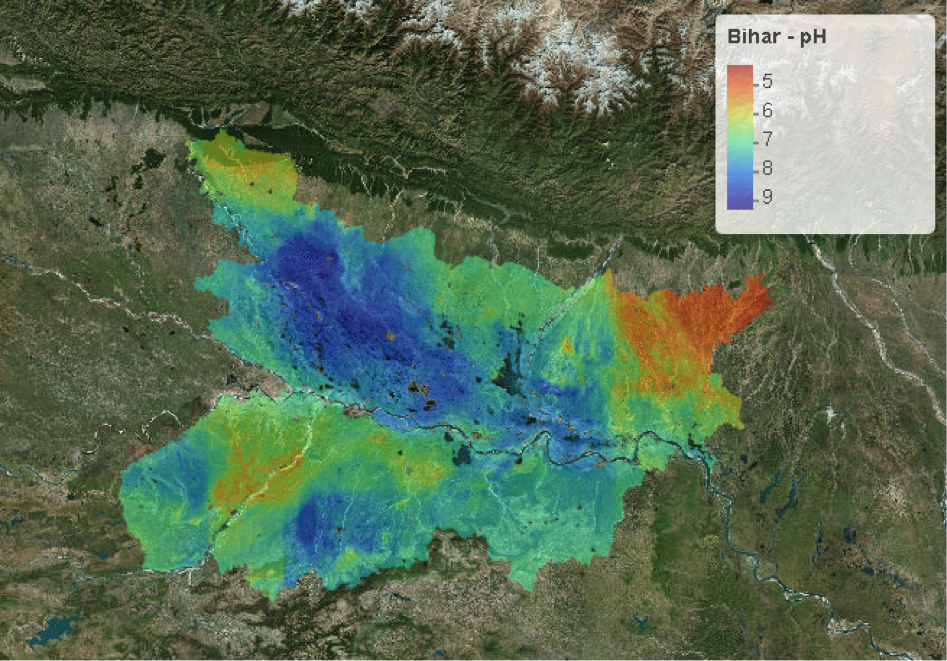

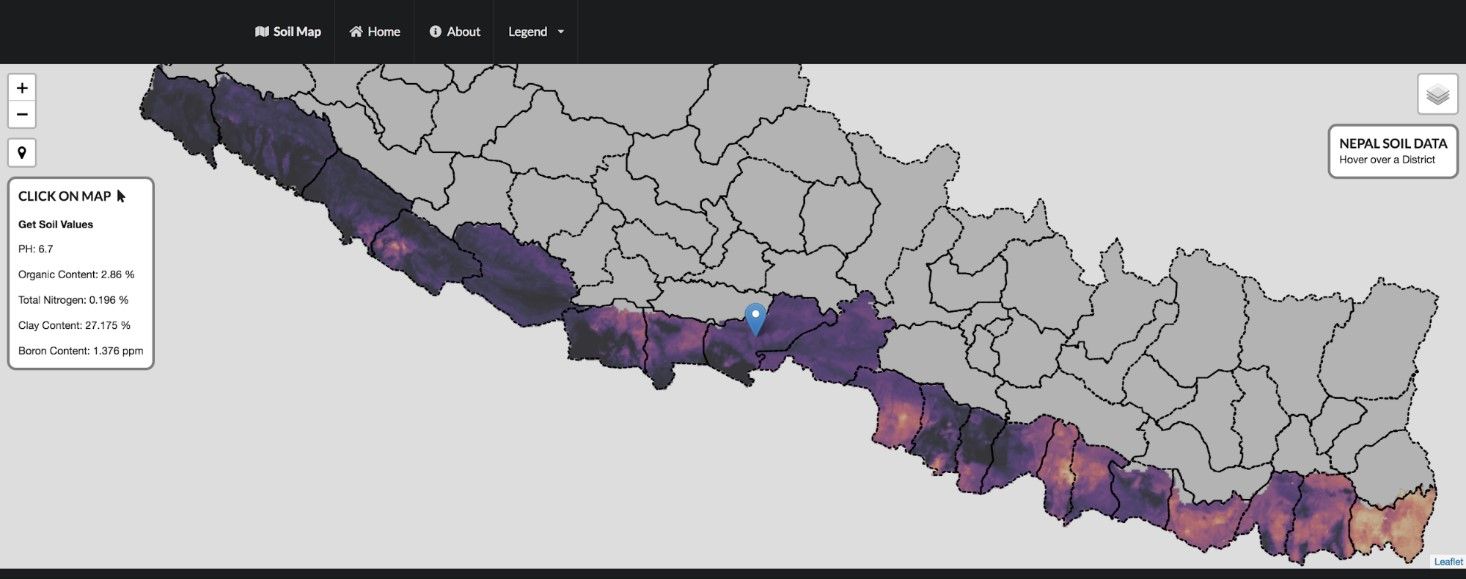

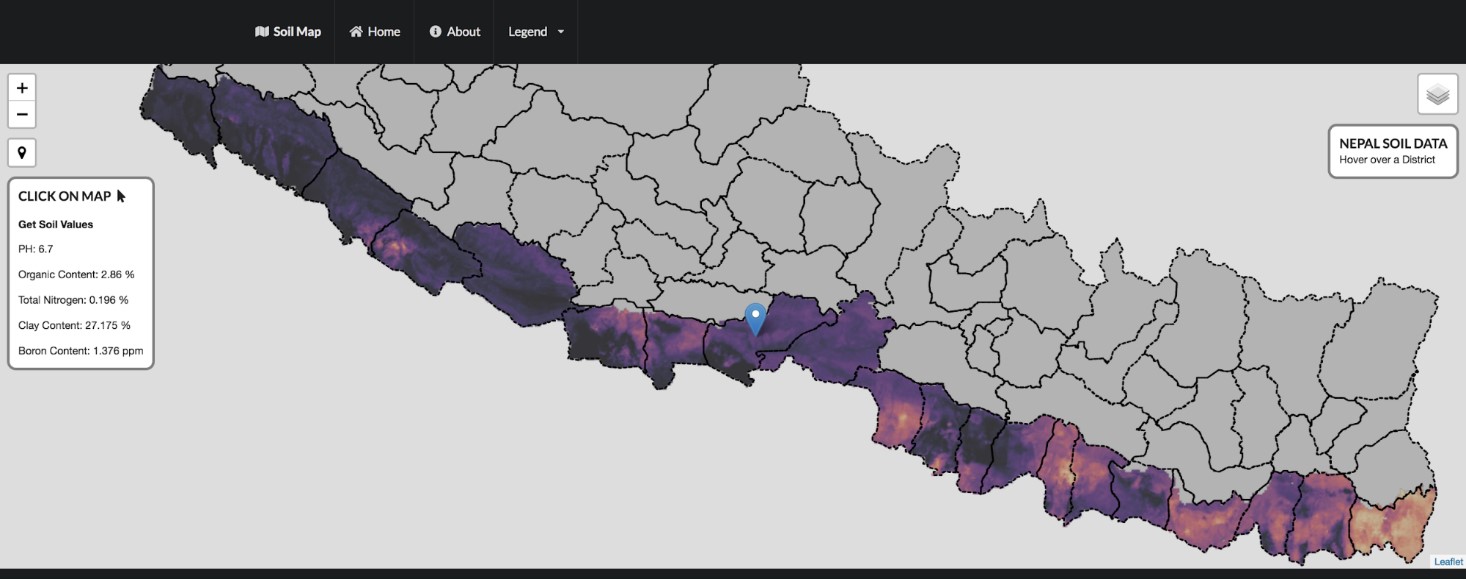

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce