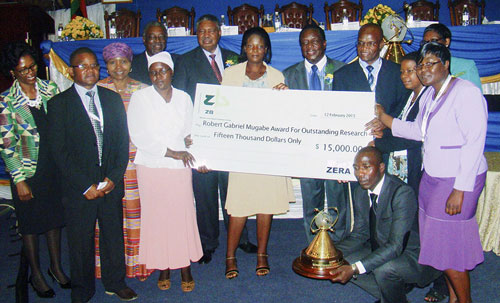

Presidential award in recognition of critical breakthrough in maize breeding in Zimbabwe

Called the “Robert Gabriel Mugabe Award” (after the Zimbabwean president), it is presented bi-annually for critical breakthroughs in research. The USD 15,000 award was presented by acting President and Vice-President, Mr. Emmerson Mnangagwa, to the Crop Breeding Institute’s National Maize Breeding Programme, for outstanding research in the production and release of the maize variety ZS265.

“This variety, for which it is receiving the Robert Gabriel Mugabe Award is a truly Zimbabwean-bred non-GMO white-grained variety with excellent tolerance to diseases, drought and low nitrogen and therefore suitable for production under dryland conditions,” read part of the citation.

CIMMYT works in partnership with the Department of Research and Specialist Services in Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanization and Irrigation Development. “We congratulate the national maize breeding program for winning this prestigious award. CIMMYT is proud and pleased that our partner is engaged, committed and as excited we ourselves are!” said Dr. Mulugetta Mekuria, CIMMYT–Southern Africa representative. “Food insecurity can be overcome if we can bring together new knowledge and skills to farmers in a very sustainable manner. There will be crop production challenges unless we integrate climate change, soil fertility and water,” he cautioned.

Magorokosho observed, “Considering that the Zimbabwe program has faced several challenges over the last several years, this is indeed a true achievement which will go down in history books, similar to the famous significant milestone that was reached in Zimbabwe in 1960 when SR-52, the world’s first single-cross hybrid, was released and made available for commercial planting.”

The variety was phenomenally successful not just in Zimbabwe, but across Africa. By 1970, 98 percent of Zimbabwe’s commercial maize area was sown to SR-52. The variety is still being grown today in of Africa, especially for green cobs.

In partnership with CIMMYT–Zimbabwe and in response to declining soil fertility and recurrent droughts as a result of climate change, the Zimbabwe national maize breeding team pioneered the development of drought and low nitrogen tolerant maize varieties in the late 1990s.

This culminated in the commercial release, since 2006, of two open pollinated varieties (ZM421 and ZM521) and seven hybrids (ZS261, ZS263, ZS265, ZS269, ZS271, ZS273 and ZS275) with combined tolerance to drought and low nitrogen. These varieties are white and of early-to-medium maturity. ZS261 is a protein-enhanced maize variety which was commercialized in Zimbabwe in 2006, while ZS263 and ZS265 have proven to be popular drought-tolerant varieties.

Also in partnership with CIMMYT–Kenya, the national maize breeding team started conventional breeding insect-resistant varieties in the country in 2009. This was in response to serious field losses from stem borer and postharvest storage losses to the maize weevil and larger grain borer. Two conventionally-bred white maize hybrids that are resistant to the stem borer will be released for commercial use this year.

In recognition of their sterling effort in using plant breeding to address low maize productivity on smallholder farms, CIMMYT’s Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa project awarded the “Best Maize Breeding Team in Southern Africa” prize to Zimbabwe a record five times from 2008 to 2014.

We join in congratulating this truly outstanding team, and look forward to their future feats.

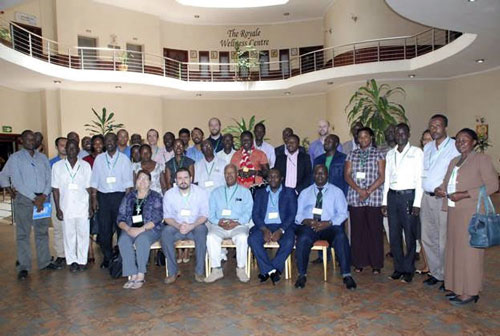

This is business unusual. IMIC-Asia is a partnership of over 40 institutions (seed companies, national programs and foundations) formed by CIMMYT to develop and share improved maize inbreds and hybrids for targeted impacts on the hybrid maize scenario in Asia. This is all done through a shared research investment. Modelled on ICRISAT’s successful consortium on pearl millet, IMIC-Asia, which was established in 2010, has so far developed and distributed over 1,500 improved inbred lines developed by CIMMYT to members for use in new inbred line development or in heterotic hybrid combinations of the partners. IMIC germplasm incorporates trait priorities jointly identified by members while still maintaining the typical vast genetic diversity of CIMMYT germplasm. Through the germplasm selected at field days, members have also sampled the diversity in terms of tolerance to major abiotic stresses (drought and heat) and biotic stresses, a key strength in CIMMYT’s tropical maize germplasm base.

This is business unusual. IMIC-Asia is a partnership of over 40 institutions (seed companies, national programs and foundations) formed by CIMMYT to develop and share improved maize inbreds and hybrids for targeted impacts on the hybrid maize scenario in Asia. This is all done through a shared research investment. Modelled on ICRISAT’s successful consortium on pearl millet, IMIC-Asia, which was established in 2010, has so far developed and distributed over 1,500 improved inbred lines developed by CIMMYT to members for use in new inbred line development or in heterotic hybrid combinations of the partners. IMIC germplasm incorporates trait priorities jointly identified by members while still maintaining the typical vast genetic diversity of CIMMYT germplasm. Through the germplasm selected at field days, members have also sampled the diversity in terms of tolerance to major abiotic stresses (drought and heat) and biotic stresses, a key strength in CIMMYT’s tropical maize germplasm base.

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (

A public-private partnership that, along with CIMMYT, involves national research organizations such as the Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization (

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

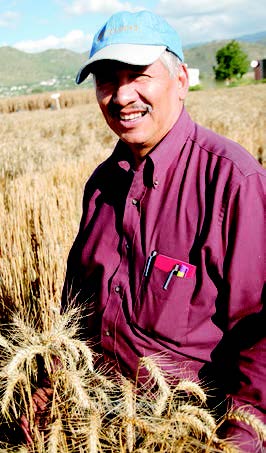

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE  When BM Prasanna, CIMMYT’s global maize program director, opened the 12th Asian Maize Conference and Expert Consultation on “Maize for Food, Feed, Nutrition and Environmental Security” in Bangkok last week he said that boosting maize crops would be a key to food security. In China, maize is the number one crop in acreage, covering 35.26 million hectares (87 million acres) in 2013, an area comparable to that of the United States, Prasanna said. The big questions are whether or not China can increase yields before 2020 to avoid being the largest importer of maize and whether Asia can meet the demand for maize “by shortening, widening and improving the breeding funnel,” Prasanna said.

When BM Prasanna, CIMMYT’s global maize program director, opened the 12th Asian Maize Conference and Expert Consultation on “Maize for Food, Feed, Nutrition and Environmental Security” in Bangkok last week he said that boosting maize crops would be a key to food security. In China, maize is the number one crop in acreage, covering 35.26 million hectares (87 million acres) in 2013, an area comparable to that of the United States, Prasanna said. The big questions are whether or not China can increase yields before 2020 to avoid being the largest importer of maize and whether Asia can meet the demand for maize “by shortening, widening and improving the breeding funnel,” Prasanna said.