Reaching women with improved maize and wheat

By 2050, global demand for wheat is predicted to increase by 50 percent from today’s levels and demand for maize is expected to double. Meanwhile, these profoundly important and loved crops bear incredible risks from emerging pests and diseases, diminishing water resources, limited available land and unstable weather conditions – with climate change as a constant pressure exacerbating all these stresses.

Accelerating Genetic Gains in Maize and Wheat for Improved Livelihoods (AGG) is a new 5-year project led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) that brings together partners in the global science community and in national agricultural research and extension systems to accelerate the development of higher-yielding varieties of maize and wheat.

Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), AGG fuses innovative methods to sustainably and inclusively improve breeding efficiency and precision to produce seed varieties that are climate-resilient, pest- and disease-resistant, highly nutritious, and targeted to farmers’ specific needs.

AGG seeks to respond to the intersection of the climate emergency and gender through gender-intentional product profiles for its improved seed varieties and gender-intentional seed delivery pathways.

AGG will take into account the needs and preferences of female farmers when developing the product profiles for improved varieties of wheat and maize. This will be informed by gender-disaggregated data collection on current varieties and preferred characteristics and traits, systematic on-farm testing in target regions, and training of scientists and technicians.

To encourage female farmers to take up climate-resilient improved seeds, AGG will seek to understand the pathways by which women receive information and improved seed and the external dynamics that affect this access and will use this information to create gender-intentional solutions for increasing varietal adoption and turnover.

“Until recently, investments in seed improvement work have not actively looked in this area,” said Olaf Erenstein, Director of CIMMYT’s Socioeconomics Program at a virtual inception meeting for the project in late August 2020. Now, “it has been built in as a primary objective of AGG to focus on […] strengthening gender-intentional seed delivery systems so that we ensure a faster varietal turnover and higher adoption levels in the respective target areas.”

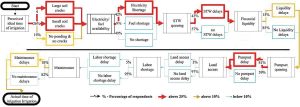

In the first year of the initiative, the researchers will take a deep dive into the national- and state-level frameworks and policies that might enable or influence the delivery of these new varieties to both female and male farmers. They will analyze this delivery system by mapping the seed delivery paths and studying the diverse factors that impact seed demand. By understanding their respective roles, practices, and of course, the strengths and weaknesses of the system, the researchers can diagnose issues in the delivery chain and respond accordingly.

Once this important scoping step is complete, the team will design a research plan for the following years to understand and influence the seed information networks and seed acquisition. It will be critical in this step to identify some of the challenges and opportunities on a broad scale, while also accounting for the related intra-household decision-making dynamics that could affect access to and uptake of these improved seed varieties.

“It is a primary objective of AGG to ensure gender intentionality,” said Kevin Pixley, Director of CIMMYT’s Genetic Resources Program and AGG project leader. “Often women do not have access to not only inputs but also information, and in the AGG project we are seeking to help close those gaps.”

Cover photo: Farmers evaluate traits of wheat varieties, Ethiopia. (Photo: Jeske van de Gevel/Bioversity International)

Nine

Nine