Three technologies that are changing agriculture in Bangladesh

In agrarian countries like Bangladesh, agriculture can serve as a powerful driving force to not only raise family income, but also the nation’s entire economy.

Consistent policy and investments in technology, rural infrastructure and human capital boosted food security by tripling the Bangladesh’s food grain production from 1972 to 2014. Between 2005 and 2010, agriculture accounted for 90 percent of poverty reduction in the country.

Bangladesh is now threatened by increasing droughts, flooding and extreme weather events due to climate change. In response, rural communities are adapting through innovative, localized solutions that combine sustainable practices and technologies.

“Mechanization is a very important part of the future of agriculture in Bangladesh,” said Janina Jaruzelski, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) mission director in Bangladesh, during a visit to areas where the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is helping commercialize three agricultural machinery technologies – axial flow pumps, reapers and seed drills – to help farmers thrive under increasingly difficult growing conditions.

Below we detail how these three technologies are transforming farming across Bangladesh.

Axial flow pumps

The axial flow pump is an inexpensive surface water irrigation technology that can reduce costs up to 50 percent at low lifts – areas where the water source is close to the field surface, and therefore is easy to pump up to irrigate fields. Surface water irrigation involves deploying water through low-lift irrigation pumps like the axial flow pump and canal distribution networks managed by water sellers who direct water to farmers’ fields.

For example, 24-year old Mosammat Lima Begum, who lives in a village in Barisal District in Bangladesh, gained access to an axial flow pump and training on its use through CIMMYT’s Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA). After the training, Begum started a business providing irrigation services to her neighbors, boosting her household income by nearly $400 in one year.

Groundwater extraction – a common approach to irrigation in much of South Asia – can result in high energy costs and present health risks due to natural arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh. Surface water offers a low-energy and low-carbon emissions alternative.

For more information on how axial flow pumps and surface water irrigation help farmers, click here.

Reapers

Reapers allow farmers to mechanically harvest and plant the next season’s crops, and can save farmers 30 percent their usual harvesting costs. The two-wheeled mechanical reaper is particularly popular in Bangladesh, especially among women since it’s easy to maneuver. It also helps farmers cope with increasing labor scarcity — a trend that has continued to rise as the country develops economically and more people leave rural areas for off-farm employment.

Like the axial flow pump, local service providers with reapers – entrepreneurs who purchase agricultural machinery and rent out their services – are now offering their harvesting services to smallholder farmers at an affordable fee.

Learn more about how reapers can reduce the cost of harvesting and risk of crop damage, making them a key tool to boost farmer efficiency in Bangladesh here.

Seed fertilizer drills

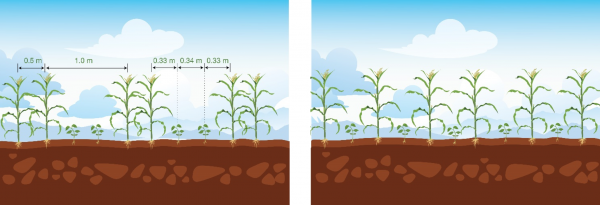

Seed fertilizer drills till, plant and fertilize crops in lines simultaneously and with greater precision. These drills are frequently used as attachments on two-wheeled tractors.

Around 66 service providers in Barisal, Bangladesh have cultivated more than 640 hectares of land using seed drills for over 1,300 farmers since 2013. These drills cut 30 percent of their fuel costs compared to traditional power tillers, saving them about $58 and 60 hours of labor per hectare. In south-western Bangladesh where USAID’s Feed the Future initiative operates, 818 service providers have cultivated more than 25,500 hectares of land using seed drills for 62,000 small holder farmers till to date.

These drills can also allow farmers to plant using conservation agriculture practices like strip tilling, a system that tills only small strips of land into which seed and fertilizer are placed, which reduces production costs, conserves soil moisture and help boost yields.

Since 2013, CIMMYT has facilitated the sale of over 2,000 agricultural machines to more than 1,800 service providers, reaching 90,000 farmers. Through the CSISA Mechanization and Irrigation project, CIMMYT will continue to transform agriculture in southern Bangladesh by unlocking the potential productivity of the region’s farmers during the dry season through surface water irrigation, efficient agricultural machinery and local service provision.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Modern data systems are essential to monitor, manage and plan actions taken by governments to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, according to the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), an advisory body to the United Nations Secretary General, and to the Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (TReENDS), an independent group of international experts working on data-related fields.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Modern data systems are essential to monitor, manage and plan actions taken by governments to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, according to the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), an advisory body to the United Nations Secretary General, and to the Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (TReENDS), an independent group of international experts working on data-related fields.