Special issue on gender research in agriculture highlights CIMMYT’s work on gender inclusivity

A new special issue on gender research in agriculture highlights nine influential papers published in the past three years on gender research on crop systems including maize.

The virtual special issue, published earlier this month in Outlook on Agriculture, features work by International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) scientists on gender inclusivity in maize systems in Africa and South Asia.

In the Global South, women contribute substantial labor to agriculture but continue to face barriers in accessing agricultural resources, tools and technologies and making decisions on farms.

Combatting gender inequality is crucial for increasing agricultural productivity and reducing global hunger and poverty and should be a goal in and of itself. Evidence suggests that if women in the Global South had access to the same productive resources as men, farm yields could rise by up to 30 percent, increasing total agricultural output by up to 4 percent and decreasing the number of hungry people around the world by up to 17 percent.

The latest virtual special issue includes a review of existing research by CIMMYT gender experts, exploring issues and options in supporting gender inclusivity through maize breeding and the current evidence of differences in male and female farmers’ preferences for maize traits and varieties. The team also identified key research priorities to encourage more gender-intentional maize breeding, including innovative methods to assess farmer preferences and increased focus in intrahousehold decision-making dynamics.

The issue also features a study by CIMMYT and Rothamsted Research researchers on differences in preferred maize traits and farming practices among female and male farmers in southern Africa. The team found that female plot managers and household heads were more likely to use different maize varieties and several different farming practices to male plot managers and household heads. Incorporating farming practices used by female farmers into selection by maize breeding teams would provide an immediate entry point for gender-intentionality.

Also included is a recent paper by CIMMYT gender researchers which outlines the evidence base for wheat trait preferences and uptake of new farming technologies among male and female smallholder farmers in Ethiopia and India. The team highlight the need for wheat improvement programs in Ethiopia and India to include more gender-sensitive technology development, evaluation and dissemination, covering gender differences in wheat trait preferences, technology adoption and associated decision-making and land-use changes, as well as economic and nutritional benefits.

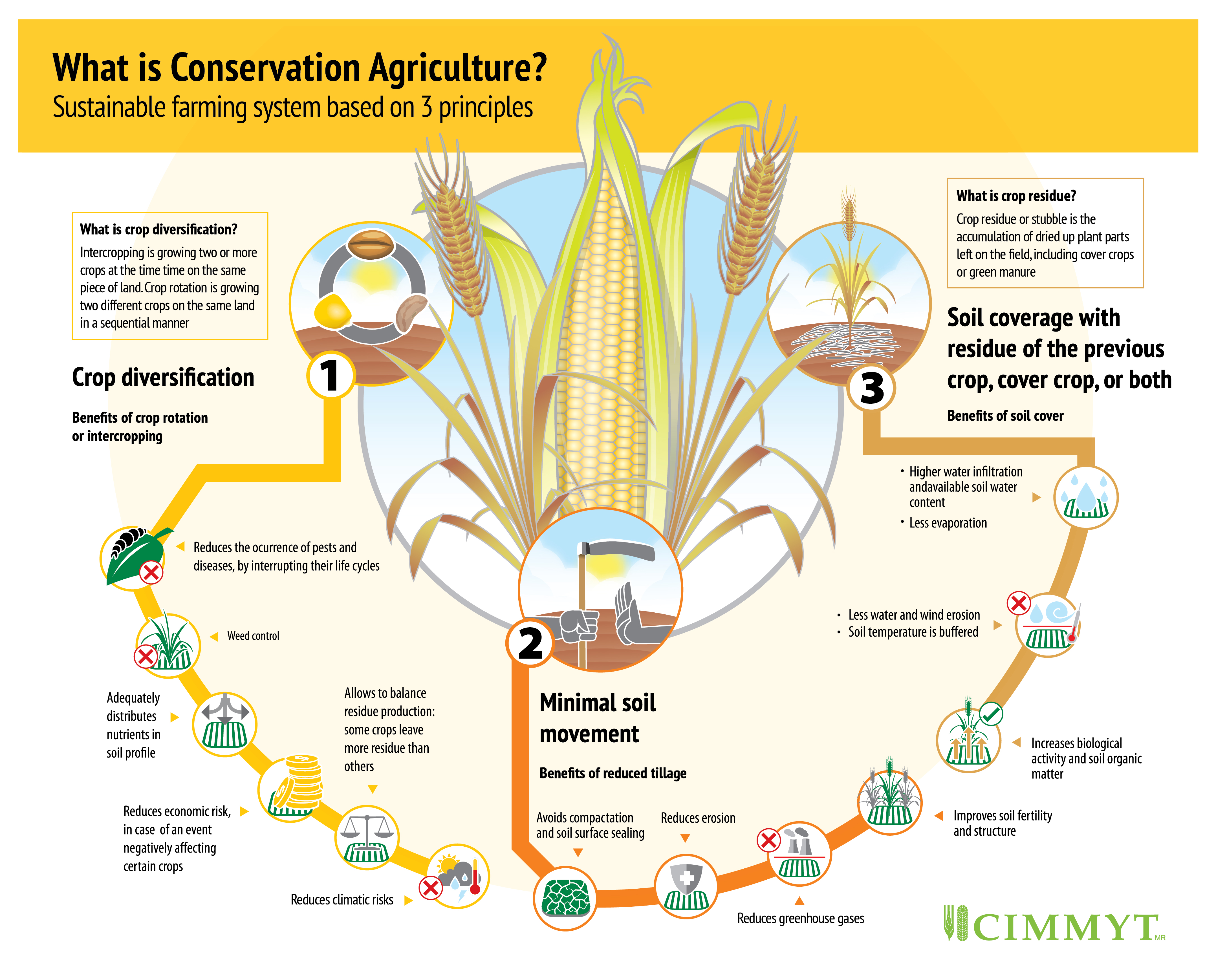

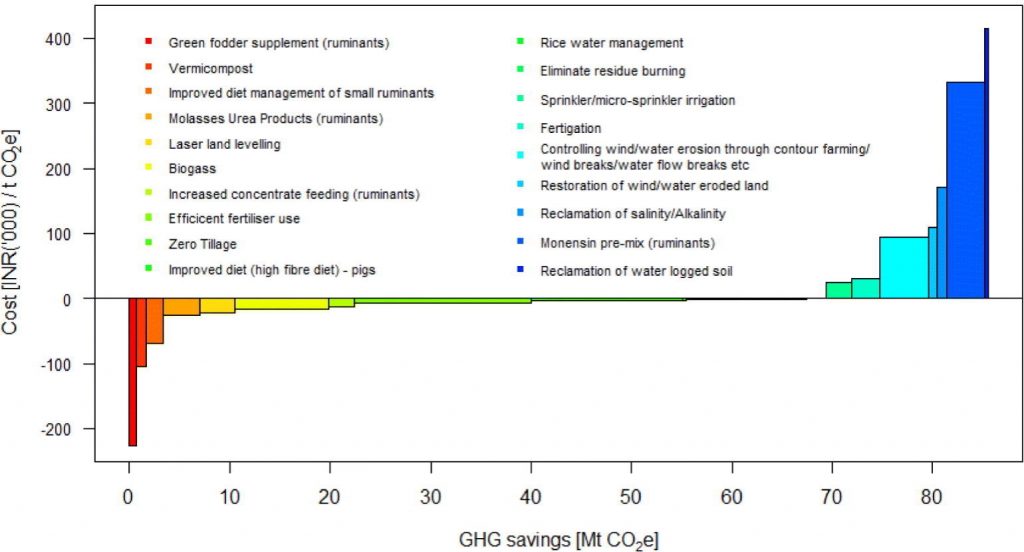

In a study carried out in the Eastern Gangetic Plains of South Asia, CIMMYT scientists investigated how changes in weed management practices to zero tillage – a method which minimizes soil disturbance – affect gender roles. The team found that switching to zero tillage did not increase the burden of roles and responsibilities to women and saved households valuable time on the farm. The scientists also found that both women and men’s knowledge of weed management practices were balanced, showing that zero tillage has potential as a gender inclusive farming practice for agricultural development.

Also featured in the special issue is a study by CIMMYT experts investigating gender relations across the maize value chain in rural Mozambique. The team found that men were mostly responsible for marketing maize and making decisions at both the farm level and higher levels of the value chain. The researchers also found that cultural restrictions and gender differences in accessing transport excluded women from participating in markets.

Finally, the collection features a study authored by researchers from Tribhuvan University, Nepal and CIMMYT exploring the interaction between labour outmigration, changing gender roles and their effects on maize systems in rural Nepal. The scientists found that the remittance incomes sent home by migrants and raising farm animals increased maize yields. They further found that when women spent more time doing household chores, rearing farm animals and engaging in community activities, maize yields suffered, although any losses were offset by remittance incomes.

Read the study: Virtual Special Issue: Importance of a gender focus in agricultural research for development

Cover photo: Women make up a substantial part of the global agriculture workforce, but their role is often limited. (Credit: Apollo Habtamu/ILRI)