EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major World Food Prize award for Bram Govaerts.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major World Food Prize award for Bram Govaerts.

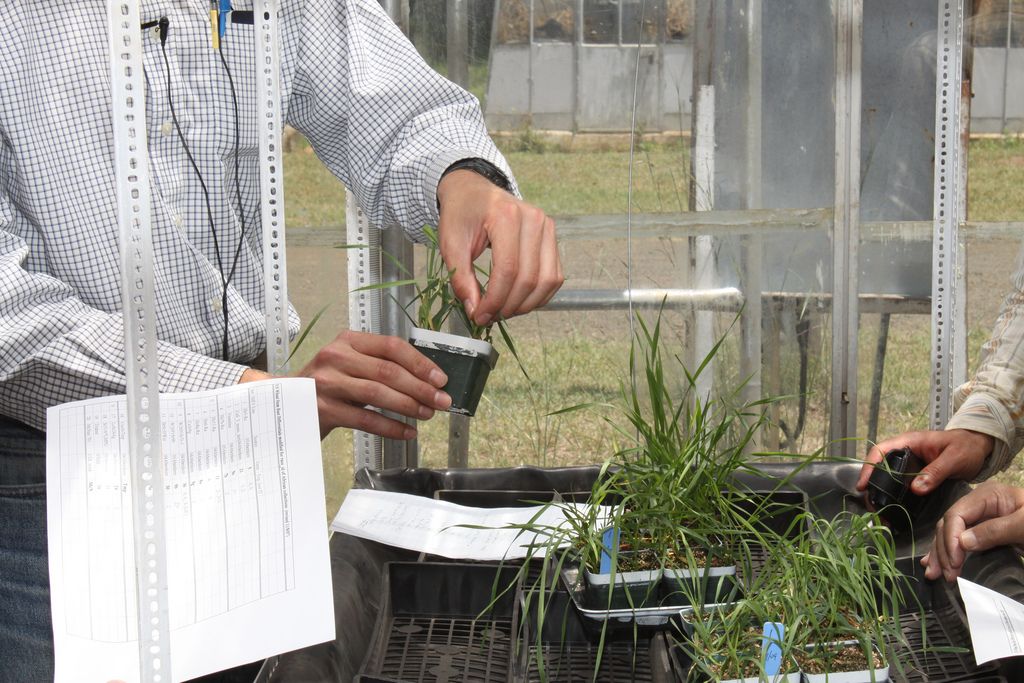

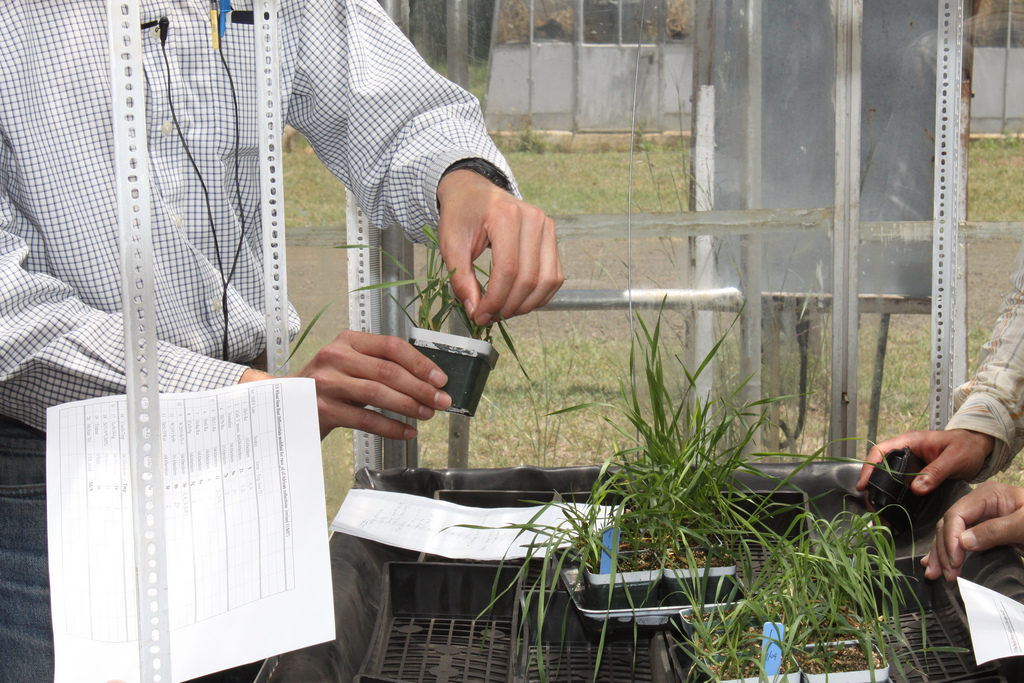

As associate director of the Global Conservation Agriculture Program at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Govaerts works with farmers to help them understand how minimal soil disturbance, permanent soil cover and crop rotation can simultaneously boost yields, increase profits and protect the environment.

Govaerts, winner of the 2014 Borlaug Field Award , played a major role in developing a Mexican initiative known as the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro), and in June 2014 the 35-year-old assumed leadership of the project, spearheading the coordination of related initiatives throughout Latin America.

According to Govaerts, there are two choices – “Either agricultural production is going to grow in unsustainable ways, depleting our resources, or we take action now, investing in sustainable agriculture so that it can be a motor for growth as well as a motor for sustainable development.”

MasAgro is a partnership led by Mexico’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food and CIMMYT involving more than 100 agricultural research organizations. It offers training and technical support for farmers in conservation agriculture and gives them access to high-yielding, conventionally bred seeds.

The overall aims of MasAgro include raising the yield potential of wheat by 50 percent and increasing Mexico’s annual production by 350,000 tons (318,000 metric tons) in 10 years. Goals also include raising the production of maize in rainfed areas.

MasAgro’s “Take It to the Farmer” component was inspired by a statement made by the late CIMMYT scientist Norman Borlaug who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. He believed that scientists should work closely with farmers, an idea central to CIMMYT’s overall approach to agricultural research and practice. Borlaug led the development of semi-dwarf wheat varieties in the mid-20th century that helped save more than 1 billion lives in Pakistan, India and other areas of the developing world. He also founded the World Food Prize .

“Take it to the Farmer” integrates technological innovation with small-scale farming systems for maize and wheat crops, while minimizing harmful impacts on the environment. Farmers on more than 94,000 hectares (232,280 acres) have switched to sustainable systems using MasAgro technologies, while farmers on another 600,000 hectares are receiving training and information to improve their agricultural techniques and practices. Techniques include crop diversification, reducing tilling of the soil and leaving crop residue on the fields.

Govaerts, who has also worked on conservation agriculture projects in Ethiopia and India, discussed his work after winning the award.

Q: What inspired the “Take it to the Farmer” component of the MasAgro project?

A: The strategy stemmed from the fact that there’s a great deal of information out there today for farmers, starting with seed varieties. Farmers have many choices to make about technology to increase productivity, but they need to understand how to integrate it and make it sustainable. We work closely with farmers to develop conservation-based agricultural systems so that they can generate high, stable crop yields over time. Doing this offers farmers the best opportunity for higher incomes, but also lowers environmental impact.

MasAgro helps the farmers develop an agronomic system – including the technology. In that way it’s not so much taken to the farmers, but it’s developing a system together with the farmer. We innovate with the farmers and connect them to a working value chain and we then combine what we call our hub approach. We’re connecting research platforms with farm innovation modules and from there we develop systems influenced by farmer knowledge.

Q: Is it possible for this to work on any farm in any location?

A: The key is to adapt to the specific locations of each of the farmers. We have to make the strategies work for specific farming and then on top of that we need to include other technologies to make it work. Technology might simply be hand-planting, not necessarily high-tech huge machinery. It is really about establishing basic conservation agriculture principles and working together to make those basic principles work.

Q: Are you trying to help farmers achieve their agricultural goals by helping them save money by not spending on fertilizers?

A: It depends; if you’re in an area where farmers are over-fertilizing it helps to reduce costs if they don’t use fertilizers as much. On the other hand, some farmers are not using fertilizers at all so there we recommend using them in an integrated manner. There might be areas where production costs go up slightly because farmers were not investing in any inputs or technologies, but because productivity is increased in the end they have a higher return on investment.

Q: Can you give an example of a farmer who has changed practices?

A: Some smallholder farmers in Oaxaca, Mexico, are improving their production practices as they raise the local [indigenous] maize landraces. We connected them with a niche maize market in New York City. They are now exporting and selling their specialty maize to chefs in New York who use them in high-end restaurants. So they are not only increasing productivity, they are also connected to markets to sell their extra produce. The challenge now is to take this effort to scale. What we realized is that by only increasing productivity, we’re actually bringing the farmers into a risky situation unless they can find bigger markets.

We helped a novice wheat farmer who is renting land. He’s been adjusting his farming system and is now using conservation agriculture technology. As a result, because he has a slower turnaround time, when he planted his summer crop, instead of planting only 100 hectares, he jumped to 350 hectares. In a strict sense, he was not a smallholder farmer, but we work with big and small farmers.

Another example is the use of mobile phones – farmers can subscribe to a short message service, or SMS text-messaging system. Once subscribed, the farmer receives information on different topics, including technical recommendations or warnings. For example, one of the warnings we sent out during the wheat-growing season was that there was going to be an imminent frost. That led to some of the farmers irrigating their crops because that helped mitigate the damage and saved part of their crops.

Q: What challenges do you face?

We’re working with more than 150 institutions and organizations and we’re connected to more than 200,000 farmers. When Dr. Borlaug was working the world was simpler, we not only have to increase yields but we also have to work in an environmentally friendly manner. We also have to provide environmental services via agriculture and we have to make sure that farmers have sufficient income and this in a complex, institutional.

We can no longer accept that we’re just doing the science and then leave it up to others to apply the science. That’s not how it works – we scientists need to ensure that the technology is actually implemented and that it is expanded by new ideas from farmers, technicians and others along the value chain. We need to take responsibility that our knowledge and science is used and is responding to a real need. Public and private investment in agriculture should increase, especially in Latin America because it’s going to be a motor of transformation.

Q: How do you encourage farmers to change their practices?

A: We do a lot of training. In some areas our first step is bringing new seeds – connecting seed companies with a new variety CIMMYT has developed, making sure the seed system is working. There are some interventions that are rather linear – one-shot interventions. There are methods that from the beginning are going to be complicated and the farmer has to wait five years before changes are seen. That’s quite difficult, but if you can show an intervention where the farmer can store maize better and instead of losing 40 percent he’s only losing 10 percent during storage, that’s an intervention that can then start the dialogue to a more complicated system change. Much of our focus is on knowledge exchange, as well as in training and innovation.

Q: What is the significance of your award for Mexico?

A: The award has a special significance for Mexico. It recognizes Mexico’s bold decision to invest in agricultural innovation and to take responsibility not only for the country but for the region. We are proud of CIMMYT’s achievements within its host country.

Before CIMMYT’s collaboration with the Mexican government there was a real disconnect between agricultural science and the reality of farmers on the ground. As a result, this award is not only a recognition of scientific excellence, but the importance of getting the results out to the farmers. Mexico is a complex country.

Here we have all types of farmers – from large commercial farmers who exploit market opportunities for export to smallholder farmers who do not have access to markets. Mexico also hosts a wide range of unique agro-ecological environments. These circumstances offer CIMMYT scientists a unique laboratory to conduct their research and gives us an opportunity to explore new ways of doing science and connecting with farmers to ensure that science has impact.

Q: This year the World Food Prize Borlaug Dialogue was titled “Can we sustainably feed the 9 billion people on our planet by the year 2050?” What are your thoughts on the topic?

A: This is not just a numbers game. We will need to feed more than 9 billion people while working in a more complicated institutional and political environment and at the same time safeguarding natural resources. These global challenges are moving at a fast pace, so CIMMYT needs to move fast and expand its scientific excellence. We are at a turning point where we have to take advantage of these rapid changes in science and technology, which are becoming increasingly interlinked.

Working to help provide nutritional food for 9.5 billion people will be a collective effort. There won’t be one Norman Borlaug but a consortium of people working together with different expertise to achieve this goal. This will require new collaborations, especially public-private partnerships. CIMMYT is one of the best institutions to create these partnerships but we need to be better equipped for what is needed at this time. Complacency and living in the past is not an option.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Conservation agriculture, which improves the livelihoods of farmers by sustainably boosting productivity, is becoming a vital part of the rural landscape throughout Mexico and Latin America, leading to a major