Pairwise Licenses Gene Editing Tools to CIMMYT to Fast-Track Smallholder Farming Systems’ Transformation

Durham, N.C., and Texcoco, Mexico (June 12, 2025) – Pairwise has entered a landmark licensing agreement with the non-profit, international agricultural research organization CIMMYT to provide access to its Fulcrum™ gene editing platform, including the advanced SHARC™ CRISPR enzyme. This partnership will accelerate the development of improved crop varieties for smallholder farmers across 20 countries where CIMMYT implements integrated research and development initiatives.

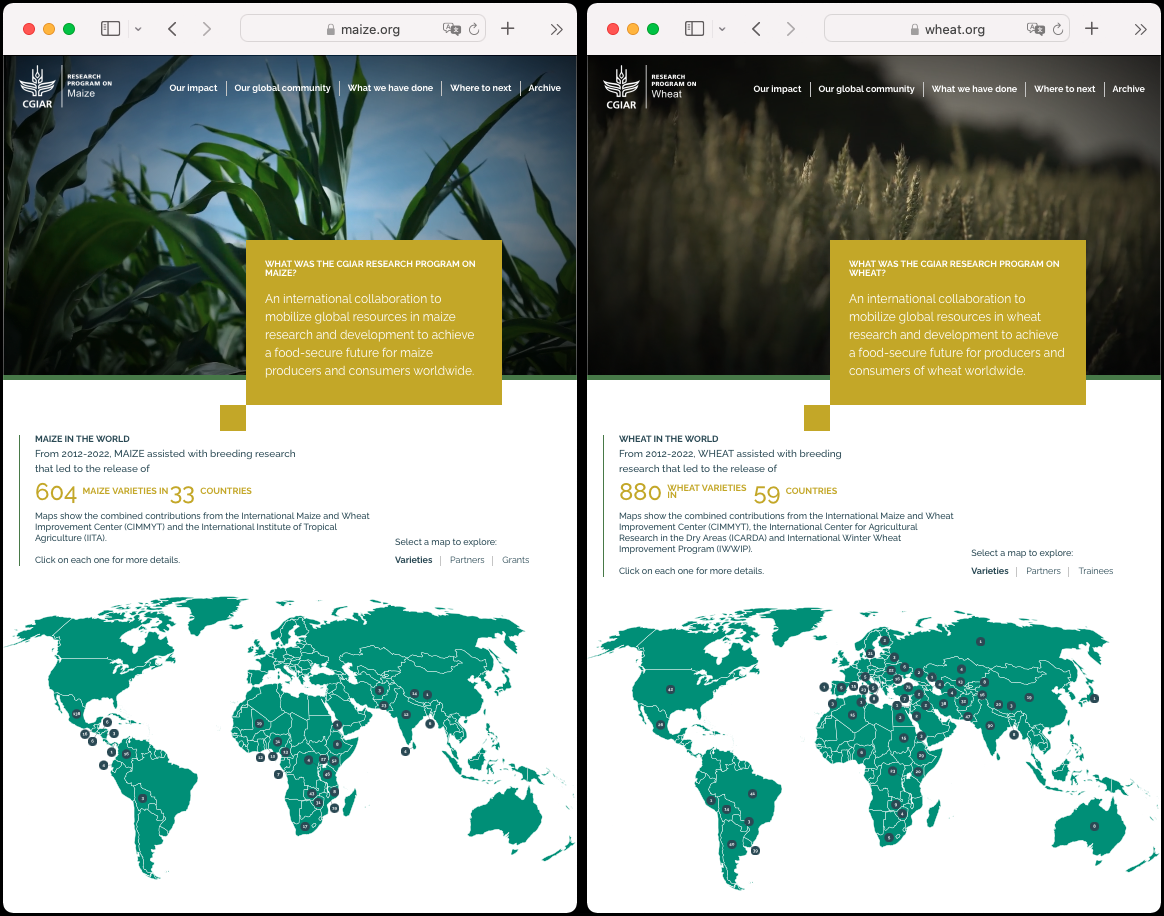

CIMMYT, based in Mexico and operating in 88 countries, is a key member of the CGIAR network and a global leader in developing sustainable solutions for food and climate security. Under the license, CIMMYT and its National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) partners will have access to Fulcrum tools in crops including maize, wheat, sorghum, and regionally important staples like pearl millet, finger millet, pigeon pea, and groundnut.

“Advanced breeding techniques replicate what happens in nature in a faster, more focused way. We’re excited to have access to a gene editing technology that allows us to not only develop new traits but also make these traits available to farmers who can benefit from them,” said Sarah Hearne, Chief Science and Innovation Officer at CIMMYT. “CIMMYT is committed to bringing new technologies to smallholder farmers in the Global South, which aims to enhance resilience and nutritional characteristics of crops and help develop livelihoods and communities. Fulcrum will speed up the delivery of the climate resilient varieties that farmers urgently need.”

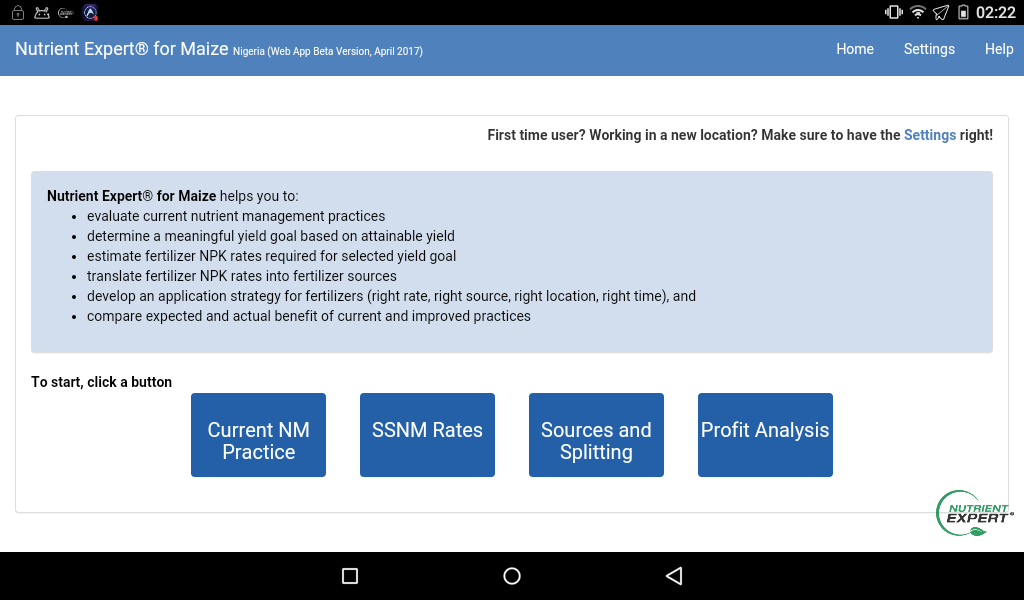

The Fulcrum™ Platform includes Pairwise-developed gene editing tools for cutting, base editing, and templated editing a toolbox which enables not only turning a characteristic on or off but also tuning it— like a dimmer switch to tailor the trait and deliver the optimum phenotype.

“Our Fulcrum Platform was built to help scientists solve urgent, real-world challenges in agriculture,” said Ian Miller, Chief Operating Officer at Pairwise. “This agreement allows CIMMYT to use our powerful CRISPR tools to deliver real-world improvements for farmers facing food insecurity and climate pressure. We outlicense to organizations like CIMMYT because Pairwise believes this transformative technology should be broadly available to those working to improve agriculture for smallholder farmers.”

Gene editing enables precision improvements in crop yield, resilience, and nutrition that could be achieved through conventional breeding but were impractical due to time and cost restraints. By making these powerful tools more accessible, this partnership accelerates impactful innovation in regions where food system improvements are most urgently needed. Through CIMMYT’s research network, these tools will be deployed in diverse environments, providing researchers with a flexible alternative for product development and a clear pathway to real-world impact.

About Pairwise

Pairwise is agriculture’s leading gene editing powerhouse, building a healthier world through partnership and plant innovation. Co-founded by the inventors of CRISPR, our Fulcrum™ Platform accelerates the development of climate-resilient, nutritious, and sustainable crops. As trusted partners to global industry leaders and nonprofit institutions, we help breeders move faster while transforming food and agriculture for farmers, consumers, and the planet. Founded in 2017 and based in Durham, NC, Pairwise is committed to delivering innovation that makes food easier to grow — and better to eat. For more information, visit www.pairwise.com.

About CIMMYT

CIMMYT is a cutting-edge, non-profit, international organization dedicated to solving tomorrow’s problems today. It is entrusted with fostering improved quantity, quality, and dependability of production systems and basic cereals such as maize, wheat, triticale, sorghum, millets, and associated crops through applied agricultural science, particularly in the Global South, through building strong partnerships. This combination enhances the livelihood trajectories and resilience of millions of resource-poor farmers while working towards a more productive, inclusive, and resilient agrifood system within planetary boundaries.

www.cimmyt.org

CIMMYT Media Contact: Jelle Boone

Head of Communications, CIMMYT

Email: j.boone@cgiar.org

Mobile: +52 595 124 7241

Pairwise Media Contact:

Email: communications@pairwise.com