In the best possible taste

The pursuit for higher and more stable yields, alongside better stress tolerance, has dominated maize breeding in Africa for a long time. Such attributes have been, and still are, essential in safeguarding the food security and livelihoods of smallholder farmers. However, other essential traits have not been the main priority of breeding strategies: how a variety tastes when cooked, its smell, its texture or its appearance.

They are now gradually coming into the mainstream of maize breeding. Researchers are exploring the sensory characteristics consumers prefer and identifying the varieties under development which have the desired qualities. Breeders may then choose to incorporate specific traits that farmers or consumers value in future breeding work. This research is also helping to accelerate varietal turnover in the last mile, as farmers have additional reasons to adopt newer varieties.

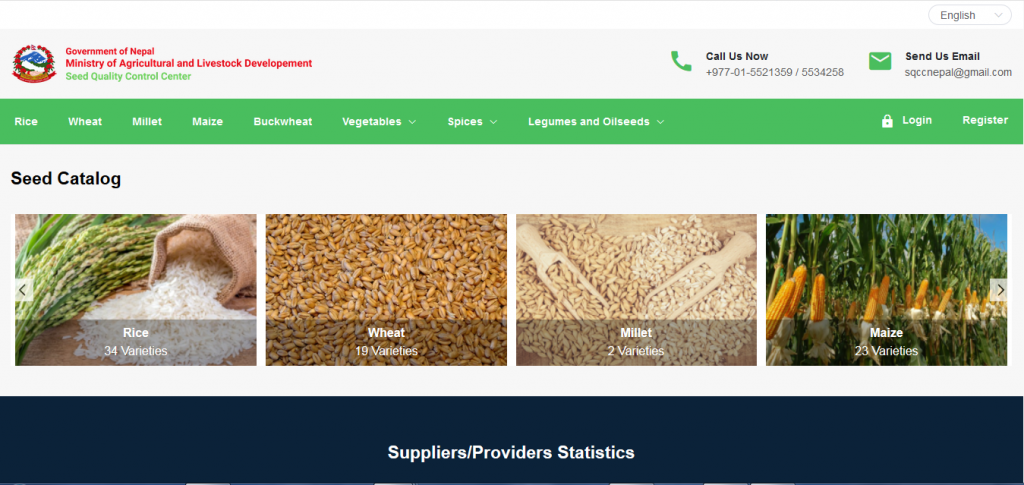

In the last five years, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) has been conducting participatory variety evaluations across East Africa. First, researchers invited farmers and purchasers of improved seed in specific agro-ecologies to visit demonstration plots and share their preferences for plant traits they would like to grow in their own farms.

In 2019 and 2020, researchers also started to facilitate evaluations of the sensory aspects of varieties.

Fresh samples of green maize, from early- to late-maturing maize varieties, were boiled and roasted. Then, people assessed their taste and other qualities. The first evaluations of this kind were conducted in Kenya and Uganda in August and September 2019, and another exercise in Kenya’s Machakos County took place in January 2020.

Similar evaluations have looked at the sensory qualities of maize flour. In March 2020, up to 300 farmers in Kenya’s Kakamega County participated in an evaluation of ugali, or maize flour porridge. Participants assessed a wider range of factors, including the aroma, appearance, taste, texture on the hand, texture in the mouth and overall impression. After tasting each variety, they indicated how likely they would be to buy it.

Tastes differ

“Farmers not only consume maize in various forms but also sell the maize either at green or dry grain markets. What we initially found is green maize consumers prefer varieties that are sweet when roasted. We also noted that seed companies were including the sensory characteristics in the maize varieties’ product profiles,” explained Bernard Munyua, Research Associate with the Socioeconomics program at CIMMYT. “As breeders and socioeconomists engage more and more with farmers, consumers or end-users, it is apparent that varietal profiles for both plant and sensory aspects have become more significant than ever before, and have a role to play in the successful turnover of new varieties.”

For researchers, this is very useful information, to help determine if it is viable to bring a certain variety to market. The varieties shared in these evaluations include those that have passed through CIMMYT’s breeding pipeline and are allocated to partners for potential release after national performance trials, as well as CIMMYT varieties marketed by various seed companies. Popular commercial varieties regions were also included in the evaluations, for comparison.

A total of 819 people participated in the evaluation exercises in Kenya and Uganda, 54% of them female.

“Currently, there is increasing demand by breeders, donors, and other agricultural scientists to understand the modalities of trait preferences of crops by women and men farmers,” said Rahma Adam, Gender and Development Specialist at CIMMYT.

That’s the way I like it

For Gentrix Ligare, from Kakamega County, maize has always been a staple food in her family. They eat ugali almost daily. The one-acre farm that she and her husband own was one of the sites used to plant the varieties ahead of the evaluation exercise. Just like her husband, Fred Ligare, she prefers ugali that is soft but absorbs more water during preparation. “I also prefer ugali that is neither very sticky nor very sweet. Such ugali would be appropriate to eat with any type of vegetable or sauce,” she said.

Fernandes Ambani prefers ugali that emits a distinct aroma while being cooked and should neither be very sweet nor plain tasting. For him, ugali should not be too soft or too hard. While it should not be very sticky, it should also not have dark spots in it. “When I like the taste, smell, texture and appearance of a particular variety when cooked, I would definitely purchase it if I found it on the market,” he said.

While the task of incorporating all the desired or multiple traits in the breeding pipeline could prove complex and costly, giving consumers what they like is one of the essential steps in enhancing a variety’s commercial success in the market, argues Ludovicus Okitoi, Director of Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Organization’s (KALRO) Kakamega Center.

“Despite continuously breeding and releasing varieties every year, some farmers still buy some older varieties, possibly because they have a preference for a particular taste in some of the varieties they keep buying,” Okitoi said. “It is a good thing that socioeconomists and breeders are talking more and more with the farmers.”

Advancements in breeding techniques may help accelerate the integration of multiple traits, which could eventually contribute to quicker varietal turnover.

“Previously, we did not conduct this type of varietal evaluations at the consumer level. A breeder would, for instance, just breed on-station and conduct national performance trials at specific sites. The relevant authorities would then grant their approval and a variety would be released. Things are different now, as you have to go back to the farmer as an essential part of incorporating end-user feedback in a variety’s breeding process,” explained Hugo de Groote, Agricultural Economist at CIMMYT.