Fidelis Namatsi Owino

Fidelis Namatsi Owino is a Research Assistant with CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program, based in Kenya.

Fidelis Namatsi Owino is a Research Assistant with CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program, based in Kenya.

Dipak Kafle is a Business Development Analyst with CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program, based in Nepal.

It’s not always easy to produce and sell new maize varieties in Malawi.

Seed companies often serve as the link between breeders and farmers, but numerous challenges — from lack of infrastructure to inconvenient finance systems — mean that the journey from the laboratory to the field is not always a smooth one.

In spite of this, the sector continues to grow, with established and up-and-coming seed companies all vying to carve their own niche in the country’s competitive maize seed market. To help bolster the industry, CIMMYT is working with around 15 seed companies in Malawi, providing them with early generation seed for CIMMYT-derived maize varieties, technical production training and marketing advice.

In a series of interviews, representatives from three of these companies share how they chose their flagship varieties and got them onto the market, and the CIMMYT support that helped them along the way.

The company started primarily because we wanted to help farmers — the issue of profits came later. The founders of Demeter Seeds saw a gap in the market for open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) and thought they could fill it. We’ve now migrated halfway into hybrids, but we still feel that we should serve both communities.

At the beginning we used to multiply and sell OPVs from CIMMYT, and we started doing our own multiplication here a few years ago. What I like about CIMMYT is they have been continuing to give us technical support. The breeding teams are our regular visitors. When they give us materials they come here, work with us, we go to the fields together. We’re so proud of this collaboration. Our whole company is based on CIMMYT germplasm since we don’t have our own breeding program to develop our own varieties.

How do you decide which varieties to work with?

When we were starting out, the decision of which varieties to work with was based on what CIMMYT recommended based on the data from on-farm trials. Most Malawian farmers use local maize varieties so it’s a good step for them to start using improved varieties – not necessarily hybrids.

Apart from the yields, what else do Malawian farmers look for? It has to be white and it has to be poundable or flint varieties with a hard endosperm. Of course, there are other attributes you have to worry about as well such as yield and drought tolerance. The seasons are changing, the rainfall period is becoming shorter so we’re looking for short-maturing materials in particular. If you have a variety that takes 90-100 days to mature, you’re OK, but if you choose one that takes 140-150, the farmer can be at risk of losing out because it doesn’t fit well into the growing season.

Having looked at those particular parameters we can decide on the variety we’re going to go for because this feeds into what our regular farmers want.

Is it easy to get farmers to buy those varieties, given that you know exactly what they’re looking for?

We’re not the only ones dealing with maize hybrids, so if you’re not aggressive enough in marketing you’ll not be able to survive.

You can’t just see that the demand is there and then put the product out. We have a marketing team within the company whose role is to market and advise the farmers. We try to listen to what’s happening on the ground, see how our varieties are performing and share results with the breeders. If you sell your seed you have to get feedback – whether it’s doing well or not.

But it can be difficult with the lack of infrastructure in Malawi. There are some places which are not accessible, so there are farmers who want your seed but you can’t reach them. Those farmers end up planting some local seed, which they might not have planted if they had access to improved varieties.

CIMMYT equals maize, so there’s very little we’d be doing without them. There has been collaboration and partnership since we started the seed business.

We got all the parent materials, expertise and production training from CIMMYT. We now even have our own CIMMYT-trained internal inspectors, who ensure that the seed that we produce meet quality standards that are required. When they were giving us the lines, they also helped us with production of the basic seed to start our maize production. Without CIMMYT, we wouldn’t be here.

You’re one of the few seed companies in Malawi producing vitamin A biofortified maize, which CIMMYT develops in partnership with HarvestPlus. How did you decide to work on that variety?

We selected the orange vitamin A maize firstly because of corporate social responsibility reasons. There is a developmental aspect to what we do, and we’re not just here for money. I think whatever we’re doing should also help the people that are buying from us. We knew that micronutrient deficiency is an issue in Malawi, so we hoped that the vitamin A biofortified maize could address some of the country’s malnutrition problems.

When the Government said it was looking at alternative ways of combating malnutrition, this was one of the proposed solutions and we thought we should be the first to do it. As of now, I think that of the 20-something lead seed businesses in Malawi, we’re one of only three producing this maize.

How challenging has it been to promote that variety?

Very, because the orange maize was not popular to begin with. In the first year, we had about 25 metric tons of seed and we didn’t even sell 10.

Yellow maize was brought in to feed people during a famine in the early 90s, so I think when people see orange maize now they are reminded of that hunger. There are still those negative associations. So we had to do some convincing, visiting farmers with HarvestPlus and telling them about the benefits.

But this is our third year and we don’t have any seed left — it’s all gone. Combined, the three companies involved in orange maize production had about 65 metric tons. But this year the demand has been around 1,050 metric tons. What we produced is not even one tenth of what is required.

Now that the orange maize has been popularized, we see demand increasing in the next five years as well. Apart from farmers, we’ve also had inquiries from people that want to use it for industrial purposes and are looking for very large quantities. Now we know, if people are looking for orange maize, we’ll be among the first to provide it.

I studied agribusiness management for my first degree and went into farming immediately after. Later I completed a Masters in Agronomy, but the moment I started talking to CIMMYT I knew that I was lacking knowledge on the technical side. Over the years I’ve attended a number of courses — maize technician courses and programs to help people in the seed industry learn about hybrids — thanks to CIMMYT. A large part of my knowledge has come from those trainings, visiting the research station in Harare and attending field days.

Global Seeds is known for its flagship product, MH34. Why did you decide to focus on that specific variety?

One of the main driving factors for us to go for MH34 was that it was not being produced by anyone else. This was a new variety that no other company had branded as their own yet, so it was a good opportunity for us to own it.

At the same time, I liked this variety because it had two lines from CIMMYT and one line that’s bred locally. It’s kind of a mix. I really liked that because it meant that it would be a bit of a challenge for anyone outside the country to produce it because they would not get that extra 25% from the Malawian line.

Did that also make it difficult for Global Seeds to produce?

It was not easy for us to get it on the market. It’s one of the stories I’m most proud of — to say we’re one of the few companies producing this variety — especially when I look back at the last three years and the work it took to get it to where we are.

We got the lines we needed from CIMMYT, but when we went to the local program to get that one last ingredient, we got less than 1.4 kilograms. Normally we would need at least 5 kilograms.

We knew we had to produce quickly to commercialize the variety, so we took 900 grams and started trying to increase the line under irrigation. Then the water supply ran out and we had to hire a water bowser. It was quite a journey but in the end we produced a handful of seed, and now the story is that this variety is flying off the shelves.

High-yielding, disease-resistant wheat varieties used by Ethiopian wheat farmers between 2015 and 2018 gave them at least 20% more grain than conventional varieties, profits of nearly $1,000 per hectare when they grew and sold seed, and generally improved food security in participating rural households.

These are the result of a project to rapidly multiply and disperse high-quality seed of new improved varieties, and the work of leading Ethiopian and international research organizations. The outcomes of this project have benefitted nearly 1.6 million people, according to a comprehensive new publication.

“Grown chiefly by smallholders in Ethiopia, wheat supports the livelihoods of 5 million farmers and their families, both as a household food crop and a source of income,” said Bekele Abeyo, wheat scientist of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), leader of the project, and chief author of the new report. “Improving wheat productivity and production can generate significant income for farmers, as well as helping to reduce poverty and improve the country’s food and nutrition security.”

Wheat production in Ethiopia is continually threatened by virulent and rapidly evolving fungal pathogens that cause “wheat rusts,” age-old and devastating diseases of the crop. Periodic, unpredictable outbreaks of stem and stripe rust have overcome the resistance of popular wheat varieties in recent years, rendering the varieties obsolete and in urgent need of replacement, according to Abeyo.

“The eastern African highlands are a hot spot for rusts’ spread and evolution,” Abeyo explained. “A country-wide stripe rust epidemic in 2010 completely ruined some susceptible wheat crops in Oromia and Amhara regions, leaving small-scale, resource-poor farmers without food or income.”

The Wheat Seed Scaling project identified and developed new rust-resistant wheat varieties, championed the speedy multiplication of their seed, and used field demonstrations and strategic marketing to reach thousands of farmers in 54 districts of Ethiopia’s major wheat growing regions, according to Abeyo. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded the project and the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) was a key partner.

Using parental seed produced by 8 research centers, a total of 27 private farms, farmer cooperative unions, model farmers and farmer seed producer associations — including several women farmer associations — grew 1,728 tons of seed of the new varieties for sale or distribution to farmers. As part of the work, 10 national research centers took part in fast-track variety testing, seed multiplication, demonstrations and training. The USDA Cereal Disease Lab at the University of Minnesota conducted seedling tests, molecular studies and rust race analyses.

A critical innovation has been to link farmer seed producers directly to state and federal researchers who supply the parental seed — known as “early-generation seed”— according to Ayele Badebo, a CIMMYT wheat pathologist and co-author of the new publication. “The project has also involved laboratories that monitor seed production and that test harvested seed, certifying it for marketing,” Badebo said, citing those accomplishments as lasting legacies of the project.

Abeyo said the project built on prior USAID-funded efforts, as well as the Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat (DRRW) and Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat (DGGW) initiatives, led by Cornell University and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Department for International Development (DFID).

Protecting crops of wheat, a vital food in eastern Africa, requires the collaboration of farmers, governments and researchers, according to Mandefro Nigussie, Director General of EIAR.

“More than 131,000 rural households directly benefited from this work,” he said. “The project points up the need to identify new resistance genes, develop wheat varieties with durable, polygenic resistance, promote farmers’ use of a genetically diverse mix of varieties, and link farmers to better and profitable markets.”

RELATED RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS:

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

Bekele Abeyo, Senior Scientist, CIMMYT.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT THE MEDIA TEAM:

Simret Yasabu, Communications officer, CIMMYT. s.yasabu@cgiar.org, +251 911662511 (cell).

PHOTOS AVAILABLE:

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.

Walter Chivasa is CIMMYT’s maize seed systems coordinator for Africa. He is responsible for co-developing and executing CIMMYT’s maize seed scaling strategies, managing and developing strategic partnerships, and implementing activities to promote the effectiveness and impacts of CIMMYT products in sub-Saharan Africa. This entails driving and documenting the impact of CIMMYT-derived varieties, contributing to the sustainability, profitability, and growth of seed company partners, and ultimately bringing the benefits of improved and affordable maize seed to smallholder farmers, who face wide-ranging constraints in sub-Saharan Africa.

Chivasa supervises scientists working to improve maize seed systems efficiency through the generation of seed production data, assisting partners in the design and implementation of seed road maps, including inbred line maintenance, production of early generation seed of CIMMYT-derived varieties, and extensive on-farm testing through a network of partners in order to accelerate the deployment of improved varieties.

Nepal’s National Seed Vision 2013-2025 identified the critical skills and knowledge gaps in the seed sector, across the value chain. Seed companies often struggle to find skilled human resources in hybrid product development, improved seed production technology and seed business management. One of the reasons is that graduates from agricultural universities might be missing on recent advancements in seed science and technology, required by the seed industry.

Researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have been collaborating with Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU) to review and update the existing curriculum on seed science and technology, for both undergraduate and postgraduate students. This work is part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Feed the Future initiative.

Realizing the need to increase trained human resources in improved seed technologies, CIMMYT researchers held discussions with representatives from the Department of Agronomy at AFU, to begin revising the curriculum on seed science and technology. Developed four years ago, the current curriculum does not encompass emerging developments in the seed industry. These include, for example, research and product development initiated by local private seed companies engaged in hybrid seed production of various crops, who want to be more competitive in the existing market.

Each year, approximately 200 bachelor’s and 10 master’s students graduate from AFU. In collaboration with CIMMYT, the university identified critical areas that need to be included in the existing curriculum and drafted new courses for endorsement by the academic council. AFU also developed short-term certificate and diploma courses in the subject of seed science and technology.

Shared knowledge

On November 20, 2019, CIMMYT, AFU and Catholic Relief Services (CRS) organized a consultation workshop with seed stakeholders from the public and private sectors, civil society and academia. Participants discussed emerging needs within Nepal’s seed industry and charted out how higher education can support demand, through a dynamic and responsive program.

Sabry G. Elias, professor at Oregon State University (OSU), discussed recent advances in seed science and technology, and how to improve productivity of smallholder farmers in Nepal. He is supporting the curriculum revision by taking relevant lessons from OSU and adapting them to Nepal’s context. Sabry shared the courses that are to be included in the new program and outlined the importance of linking graduate research with the challenges of the industry. He also stressed the importance of building innovation and the continuous evolution of academic programs.

Professors from AFU, Nepal Polytechnic Institute, Tribhuvan University, and several private colleges introduced the current courses in seed science and technology at their institutions. Santosh Marahatta, head of the Department of Agronomy at AFU, discussed the limitations of the current master’s and doctoral degree programs, and proposed a draft curriculum with integrated courses across the seed value chain. J.P. Dutta, dean of the Faculty of Agriculture at AFU, shared plans to create a curriculum that would reflect advanced practices and experiences in seed science and technology.

Scientists and researchers from Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) presented their activities and suggested key areas to address some of the challenges in the country’s seed sector.

“Our aim is to strengthen local capacity to produce, multiply and manage adequate quality seeds that will help improve domestic seed production and seed self-sufficiency,” said Mitraraj Dawadi, a representative from the Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN). “Therefore, we encourage all graduates to get hands-on experience with private companies and become competent future scientists and researchers.”

AbduRahmann Beshir, Seed Systems Lead for the NSAF project at CIMMYT, shared this sentiment. According to him, most current graduates lack practical experience on hybrid seed development, inbred line maintenance and knowledge on the general requirements of a robust seed industry. “It is important that universities can link their students to private seed companies and work together towards a common goal,” he explained. “This human resource development drive is part of CIMMYT’s efforts to help Nepal on its journey to self-reliance.”

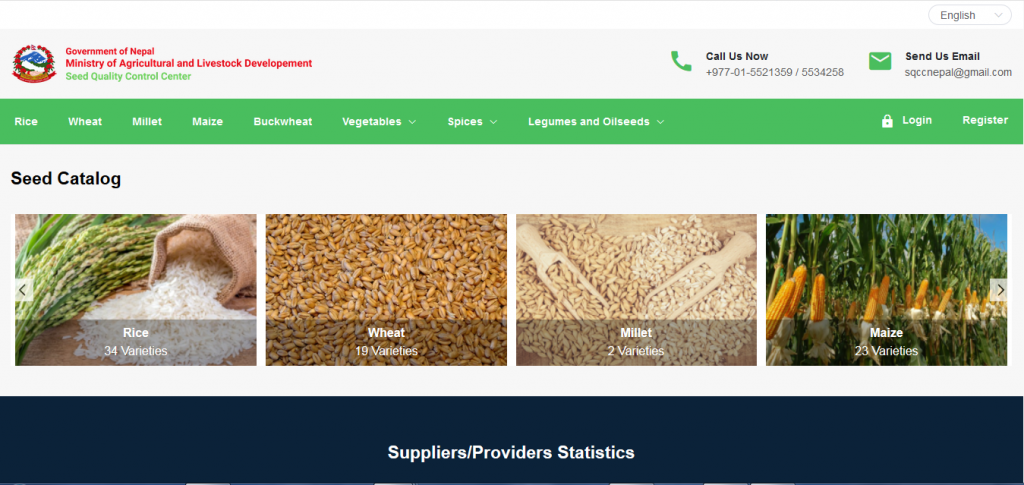

In Nepal, it takes at least a year to collate the demand and supply of a required type and quantity of seed. A new digital seed information system is likely to change that, as it will enable all value chain actors to access information on seed demand and supply in real time. The information system is currently under development, as part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

In this system, a national database allows easy access to an online seed catalogue where characteristics and sources of all registered varieties are available. A balance sheet simultaneously gathers and shares real time information on seed demand and supply by all the stakeholders. The digital platform also helps to plan and monitor seed production and distribution over a period of time.

Challenges to seed access

Over 2,500 seed entrepreneurs engaged in production, processing and marketing of seeds in Nepal rely on public research centers to get early generation seeds of various crops, especially cereals, for subsequent seed multiplication.

“The existing seed information system is cumbersome and the process of collecting information takes a minimum of one year before a seed company knows where to get the required amount and type of seed for multiplication,” said Laxmi Kant Dhakal, Chairperson of the Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN) and owner of a seed company in the far west of the country. Similarly, more than 700 rural municipalities and local units in Nepal require seeds to multiply under farmers cooperatives in their area.

One of the critical challenges farmers encounter around the world is timely access to quality seeds, due to unavailability of improved varieties, lack of information about them, and weak planning and supply management. Asmita Shrestha, a farmer in Surkhet district, has been involved in maize farming for the last 20 years. She is unaware of the availability of different types of maize that can be productive in the mid-hill region and therefore loses the opportunity to sow improved maize seeds and produce better harvests.

In Sindhupalchowk district, seed producer Ambika Thapa works in a cooperative and produces hybrid tomato seeds. Her problem is getting access to the right market that can provide a good profit for her efforts. A kilogram of hybrid tomato seed can fetch up to $2,000 in a retail and upscale market. However, she is not getting a quarter of this price due to lack of market information and linkages with buyers. This is the story of many Nepali female farmers, who account for over 60% of the rural farming community, where lack of improved technologies and access to profitable markets challenge farm productivity.

At present, the Seed Quality Control Center (SQCC), Nepal Agriculture Research Council (NARC), the Centre for Crop Development and Agro Bio-diversity Conservation (CCDABC) and the Vegetable Development Directorate (VDD) are using paper-based data collection systems to record and plan seed production every year. Aggregating seed demand and supply data and generating reports takes at least two to three months. Furthermore, individual provinces need to convene meetings to collect and estimate province-level seed demand that must come from rural municipalities and local bodies.

A digital technology solution

CIMMYT and its partners are leveraging digital technologies to create an integrated Digitally Enabled Seed Information System (DESIS) that is efficient, dynamic and scalable. This initiative was the result of collaboration between U.S. Global Development Lab and USAID under the Digital Development for Feed the Future (D2FTF) initiative, which aimed to demonstrate that digital tools and approaches can accelerate progress towards food security and nutrition goals.

FHI 360 talked to relevant stakeholders in Nepal to assess their needs, as part of the Mobile Solutions Technical Assistance and Research (mSTAR) project, funded by USAID. Based on this work, CIMMYT and its partners identified a local IT expert and launched the development of DESIS.

DESIS will provide an automated version of the seed balance sheet. Using unique logins, agencies will be able to place their requests and seed producers to post their seed supplies. The platform will help to aggregate and manage breeder, foundation and source seed, as well as certified and labelled seed. The system will also include an offline seed catalogue where users can view seed characteristics, compare seeds and select released and registered varieties available in Nepal. Users can also generate seed quality reports on batches of seeds.

“As the main host of this system, the platform is well designed and perfectly applicable to the needs of SQCC,” said Madan Thapa, Chief of SQCC, during the initial user tests held at his office. Thapa also expressed the potential of the platform to adapt to future needs.

The system will also link farmers to seed suppliers and buyers, to build a better internal Nepalese seed market. The larger goal of DESIS is to help farmers grow better yields and improve livelihoods, while contributing to food security nationwide.

DESIS is planned to roll out in Nepal in early 2020. Primary users will be seed companies, agricultural research centers, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, agrovets, cooperatives, farmers, development partners, universities, researchers, policy makers, and international institutions. The system is based on an open source software and will be available on a mobile website and Android app.

“It is highly secure, user friendly and easy to update,” said Warren Dally, an IT consultant who currently oversees the technical details of the software and the implementation process.

As part of the NSAF project, CIMMYT is also working to roll out digital seed inspection and a QR code-based quality certification system. The higher vision of the system is to create a seed data warehouse that integrates the seed information portal and the seed market information system.

Digital solutions are critical to link the agricultural market with vital information so farmers can make decisions for better production and harvest. It will not be long before farmers like Asmita and Ambika can easily access information using their mobile phones on the type of variety suitable to grow in their region and the best market to sell their products.

Access to affordable quality seed is one of the prerequisites to increase agricultural production and improve the livelihoods of Nepali farmers. However, there are significant challenges to boost Nepal’s seed industry and help sustainably feed a growing population.

Six years ago, Nepal launched its National Seed Vision 2013-2025. This strategic plan aims at fostering vibrant, resilient, market-oriented and inclusive seed systems in public-private partnership modalities, to boost crop productivity and enhance food security.

The Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), is supporting the government to enhance national policies and guidelines, and private seed companies to build competitive seed businesses and hybrid seed production.

Quality seed can increase crop yield by 15-20%. However, there are critical challenges hindering the growth of Nepal’s seed industry. Existing seed replacement rate for major cereals is low, around 15%. About 85% of Nepali farmers are unable to access recently developed improved seeds — instead, they are cultivating decades-old varieties with low yield and low profits. Some of the factors limiting the development of seed systems are the high cost of seed production and processing, the limited reach of mechanization, and the low use of conservation agriculture practices.

The demand for hybrid seeds in Nepal is soaring but research in variety development is limited. Most of the country’s supply comes from imports.

In collaboration with the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), the NSAF project team is working with seed companies and cooperatives to scale hybrid seed production of maize, tomato and rice. Through this project, CIMMYT collaborated with the Seed Quality Control Center (SQCC) and national commodity programs of the NARC to draft the first hybrid seed production and certification guidelines for Nepal to help private seed companies produce and maintain standards of hybrid seeds.

Extension and promotion activities are essential to bring improved seed varieties to farmers. Standard labelling and packaging also needs to be strengthened.

A joint effort

CIMMYT and its partners organized a two-day workshop to review the progress of the National Seed Vision. The event attracted 111 participants from government institutions, private companies and development organizations engaged in crop variety development, seed research, seed production and dissemination activities.

In the opening remarks, Yubak Dhoj G.C., Secretary of Nepal’s Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, addressed the seed sector scenario and its challenges. He stressed the importance of collaboration among seed stakeholders to meet the targets of the National Seed Vision in the next six years.

During the technical sessions, Madan Thapa, Chief of the SQCC, analyzed the current status of the National Seed Vision and highlighted the challenges as well as the opportunities to realize it.

Laxmi Kant Dhakal, Chairperson of the Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN) emphasized the importance of private sector engagement and other support areas to strengthen seed production and marketing of open-pollinated varieties and hybrids.

Tara Bahadur Ghimire, Principal Scientist at NARC, gave an overview of the status of NARC varieties, source seed and resource allocation.

Dila Ram Bhandari, former Chief of SQCC, led a discussion around the assumptions and expectations that arose while developing the National Seed Vision.

Technical leads of maize, rice, wheat and vegetables presented a road map on hybrid variety development and seed production in line with the National Seed Vision’s targets for each crop.

“A large quantity of hybrid seeds, worth millions of dollars, is being imported into Nepal each year,” explained AbduRahman Beshir, Seed Systems Lead of CIMMYT’s NSAF project. “However, if stakeholders work together and strengthen the local seed system, there is a huge potential in Nepal not only to become self-sufficient but also to export good quality hybrid seeds in the foreseeable future. Under the NSAF project we are witnessing a few seed companies that have initiated hybrid seed production of maize and tomato.”

In one of the exercises, workshop participants were divided in groups and examined different topics related to the realization of the National Seed Vision. They looked at genetic resources, hybrid and open-pollinated variety development, source seed production and supply, private sector engagement and marketing, seed extension and varietal adoption by farmers, seed quality control services, and roles of research partners and other stakeholders. The groups presented some of the major challenges and opportunities related to these topics, as well as recommendations, which will be documented and shared.

The outcomes of this mid-term review workshop will inform policy and guide the discussions at the upcoming International Seed Conference to be held in early September 2019.

Regulating hybrid seed production

At the workshop, participants thoroughly discussed the draft hybrid seed production and certification guidelines, developed under the NSAF project.

The guidelines are the first of their kind in Nepal and essential to achieve the targets of the National Seed Vision, by engaging the private sector in hybrid seed production.

Hari Kumar Shrestha, CIMMYT’s Seed Systems Officer, and other seed experts from the SQCC presented the main features and regulatory implications of the guidelines.

After the workshop, the guidelines were sent to the National Seed Board for approval.

Finance is a key driver for agricultural development, as it allows farmers and agribusinesses to improve production efficiency and adopt improved technologies. In Nepal, most of the seed in the formal sector is produced by companies and cooperatives which, like any enterprise, need access to finance in order to grow and increase their capacity.

Nepal’s Agricultural Development Strategy 2015-2035 and National Seed Vision 2013-2025 are key policy documents of the government that provide a roadmap for the development of the agricultural and seed sectors in the country.

In 2017, realizing the need to increase investments in the agricultural sector, the central bank of Nepal, Nepal Rastra Bank, adopted the Priority Sector Lending Programme (PSLP). This program mandates banks and financial institutions to allocate 10% of their loan portfolio to the agricultural sector at a subsidized interest rate of 5%.

The Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project is providing an interface between banks and seed enterprises. Commercial banks are improving their knowledge of the seed sector, its needs and growth opportunities, so they can develop loan products and credit modalities that match the requirements of seed producers and agribusinesses.

These enterprises require finances to upgrade their infrastructure, increase production and grow their businesses. The business plans of seed companies which partner with the NSAF project indicate that the average size of loan required is around $50,000 — 60% for infrastructure development and 40% for working capital. About 66% of the working capital is used to procure raw seed from contract seed growers.

Barriers to lending

Given the huge requirement for finance for seed procurement, access to loans through the PSLP can provide respite to seed companies. However, unlike in other commercial agribusiness, bank lending under the PSLP is uncommon in the seed business, as financial institutions lack understanding of the sector. Many seed companies have not been able to benefit from these loans due to perceived high risks or the lack of business plans and compliance mechanisms required by banks.

In 2018, the NSAF project team assessed the current status, challenges and opportunities in seed business financing through the PSLP. The project also facilitated a seed growers’ lending model through a tripartite agreement between Laxmi Bank Pvt. Limited, Panchashakti Seed Company and seed growers to access loans under PSLP.

On June 14, 2019, NSAF organized a meeting in collaboration with Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN) to present findings of their assessments and experiences. The meeting brought together representatives from the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, national financial institutions, private sector banks, seed companies, agricultural cooperatives and development organizations, who took part in the deliberations and also contributed to refining policy recommendations to enhance seed sector financing.

The assessments showed that PSLP awareness among farmers is low and seed growers borrowing from the informal sector were paying high interest rates, ranging from 24-36% per year. Lack of adequate business plans and compliance mechanisms for seed companies, limited eligibility criteria for PSLP, complex loan acquisition process and collateral issues were some of the factors that made funds largely inaccessible to smallholder farmers. Moreover, the terms and conditions for loan repayment stipulated by banks do not synchronize with the agricultural crop calendar and farm cash flows.

Tailor-made financing solutions

Participants in the meeting discussed ways to create a conducive environment to access financial services for agricultural producers and agribusinesses. Seed companies suggested to improve banks and financial institutions’ understanding of the agricultural markets and build their capacity to assess business opportunities. They also requested that banks simplify the documentation process for acquiring loans for farmers.

Participants from the Kisanka Lagi Unnat Biu-Bijan Karyakram (KUBK), a Nepal government project located in Rupandehi district Province 5, highlighted their model where farmers, organized into cooperatives, are linked to the Small Farmer Development Bank, which could be worth exploring in other sites.

Branchless banking promoted by NSAF is a workable strategy to provide financial services to seed growers in remote areas.

The action research also highlighted that innovative modalities, such as group guarantees, can be a feasible approach to mitigate risks to fund seed growers who do not have land registration certificates and whose land rights have not been transferred in their names. In the case of female producers, this is especially helpful, as many women are the lead decision-makers on the land registered under the name of their husbands, who are migrant workers abroad.

Utilizing the learning from this event, NSAF and SEAN will share the evidence-based policy recommendations with the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, the Ministry of Finance, the central bank and the Bankers’ Association of Nepal.

Through the NSAF project’s facilitation, banks have approved loans amounting to $2.5 million for business expansion of seven seed companies in 2018. The project will continue to support its seed partners in developing and strengthening their business plans and will facilitate linkages with commercial banks.

The Nepal Seed and Fertilizer project is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and is a flagship project in Nepal. The objective of NSAF is to build competitive and synergistic seed and fertilizer systems for inclusive and sustainable growth in agricultural productivity, business development and income generation in Nepal.

L.M. Suresh leads CIMMYT’s maize pathology efforts in sub-Saharan Africa. He regularly contributes to Global Maize Program projects that have strategic significance in maize pathology, disease diagnosis, epidemiology and disease resistance.

Suresh also works on maize lethal necrosis (MLN) phenotyping with public and private partnership at CIMMYT and the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization’s (KALRO) joint research station in Naivasha, Kenya. His team has phenotyped around 200,000 maize germplasm from various partners and 19 MLN resistant/tolerant hybrids have been released in east Africa so far. He has supported the training of more than 5000 researchers, students, extension workers, private seed company executives and farmers in rapid disease diagnosis and his contributions have helped to prevent further MLN spread throughout eastern and southern Africa.

Aparna Das is a Technical Program Manager for the Global Maize Program, working with breeding teams to implement new strategies to improve the product delivery pipeline.

Arun Kumar Joshi is engaged in developing climate-resilient, high-yielding, nutritive wheat varieties for South Asia. In addition, he is engaged in various collaborations on climate-resilient agriculture and seed system. He has facilitated the development and release of more than five dozen wheat varieties in South Asia through a significant contribution to climate resilience, disease resistance, conservation agriculture, and Zinc rich biofortification. His research findings are published in 188 refereed journal articles, 212 extension articles and manuals, 10 books or book chapters, and 136 symposia proceedings, and has a patent.

Joshi, a former Professor of Banaras Hindu University, is a fellow of the three most prestigious science academies in India – the Indian National Science Academy (INSA), the National Academy of Science in India (NASI), and the National Academy of Agriculture Sciences (NAAS). In 2014, he was awarded the Jeanie Borlaug Laube WIT Mentor Award from the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative at Cornell University.

Adefris Teklewold is a senior scientist and leads the Nutritious Maize for Ethiopia Project (NuME). He is also involved in breeding quality protein maize varieties and seed system development.

NuME fights malnutrition and food insecurity for resource-poor smallholder farmers in Ethiopia, especially among women and young children, through the widespread adoption, production and utilization of quality protein maize. The project is implemented in drought-prone, moist mid-altitude and highland areas of maize growing agroecologies in focal districts of four major maize producing and consuming regions of Ethiopia. NuME was started in 2012 and will conclude in March 2019.

Led by CIMMYT and funded by Global Affairs Canada, NuME is implemented in collaboration with Ethiopian research institutions, international non-governmental organizations, universities, farmer unions and public and private seed companies operating throughout the country.

B.M. Prasanna is a Distinguished Scientist and Regional Director for Asia at CIMMYT.

Since 2010, Prasanna, as the Global Maize Program Director, has provided technical oversight for a wide range of multi-institutional projects focused on the development and deployment of elite, stress-resilient, and nutritionally enriched maize varieties across the tropics of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He has also spearheaded the application of innovative tools and technologies aimed at enhancing genetic gains and improving breeding efficiency.

Prasanna led the CGIAR Research Program MAIZE from 2015 till 2021, an alliance of over 300 research and development institutions globally. He has been at the forefront in tackling the challenges of maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease in eastern Africa (since 2011), and the Fall Armyworm in Africa and Asia (since 2016 and 2018, respectively).

Together with an array of partners globally, Prasanna and the wider CGIAR team have formulated the OneCGIAR Plant Health Initiative in 2021. Prasanna is currently also serving as the Leader of the Plant Health Initiative, involving 10 CGIAR centers and over 80 national and international partners.

Recipient of several awards and recognitions, Prasanna has published over 200 research articles in various international journals of repute, and has a Scopus h-index of 46, and a Google Scholar h-index of 61.