Ravi Singh earns Lifetime Achievement award from BGRI

World-renowned plant breeder Ravi Singh, whose elite wheat varieties reduced the risk of a global pandemic and now feed hundreds of millions of people around the world, has been announced as the 2021 Borlaug Global Rust Initiative (BGRI) Lifetime Achievement Award recipient.

Singh, distinguished scientist and head of Global Wheat Improvement at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), endowed hundreds of modern wheat varieties with durable resistance to fungal pathogens that cause leaf rust, stem rust, stripe rust and other diseases during his career. His scientific efforts protect wheat from new races of some of agriculture’s oldest and most devastating diseases, safeguard the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in the most vulnerable areas in the world, and enhance food security for the billions of people whose daily nutrition depends on wheat consumption.

“Ravi’s innovations as a scientific leader not only made the Cornell University-led Borlaug Global Rust Initiative possible, but his breeding innovations are chiefly responsible for the BGRI’s great success,” said Ronnie Coffman, vice chair of the BGRI and international professor of global development at Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “Perhaps more than any other individual, Ravi has furthered Norman Borlaug’s and the BGRI’s goal that we maintain the global wheat scientific community and continue the crucial task of working together across international borders for wheat security.”

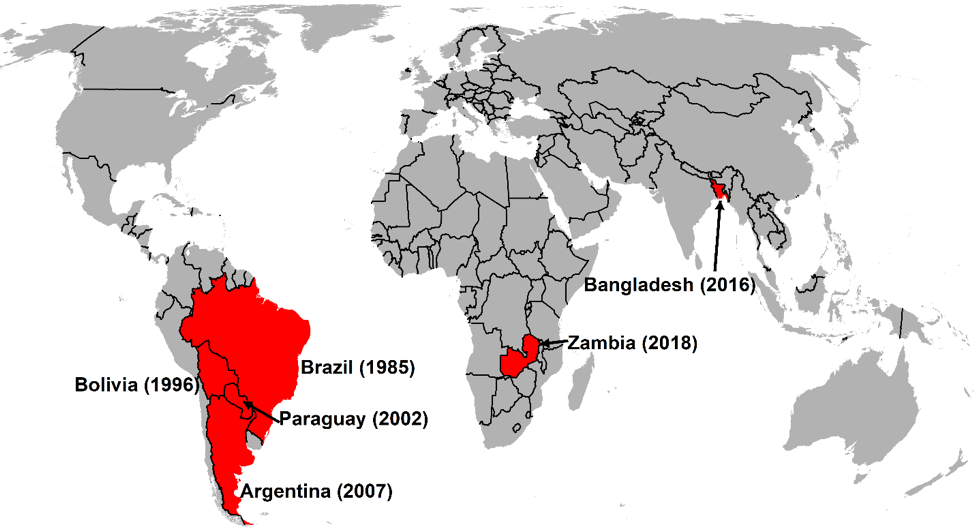

In the early 2000s, when a highly virulent rust race discovered in East Africa threatened most of the world’s wheat, Singh took a key leadership role in the formation of a global scientific coalition to combat the threat. Along with Borlaug, Coffman and other scientists, he served as a panel member on the pivotal report alerting the international community to the Ug99 outbreak and its potential impacts to global food security. That sounding of the alarm spurred the creation of the BGRI and the collaborative international effort to stop Ug99 before it could take hold on a global scale.

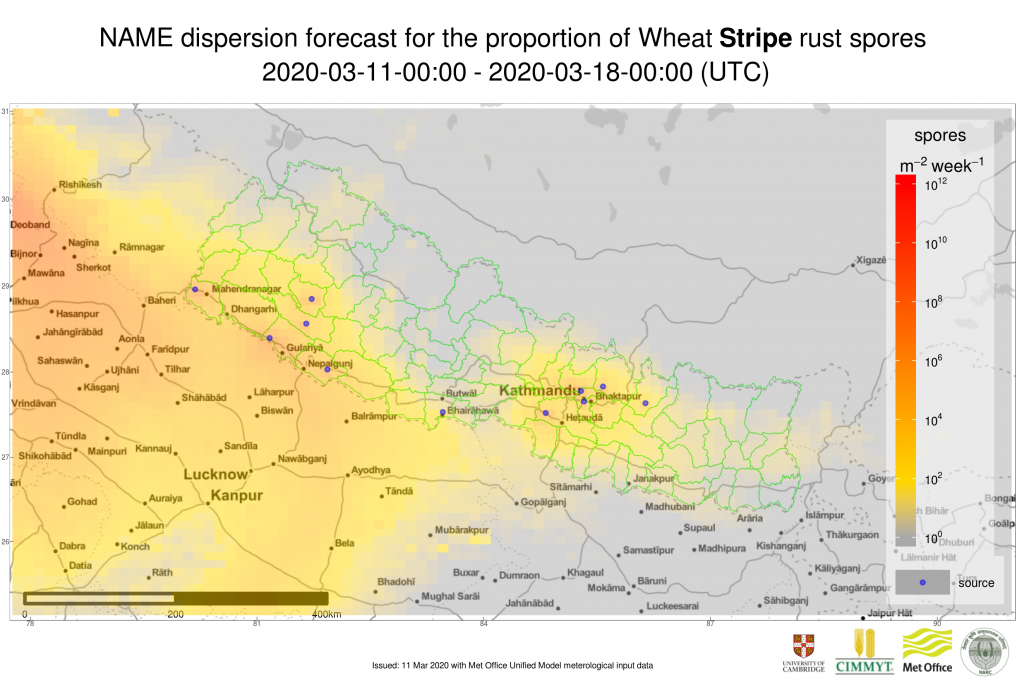

As a scientific objective leader for the BGRI’s Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat and Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat projects, Singh led efforts to generate and share a series of elite wheat lines featuring durable resistance to all three rusts. The results since 2008 include resistance to the 12 races of the Ug99 lineage and new, high-temperature-tolerant races of stripe rust fungus that had been evolving and spreading worldwide since the beginning of the 21st century.

“Thanks to Ravi Singh’s vision and applied science, the dire global threat of Ug99 and other rusts has been averted, fulfilling Dr. Borlaug’s fervent wishes to sustain wheat productivity growth, and contributing to the economic and environmental benefits from reduced fungicide use,” Coffman said. “Ravi’s innovative research team at CIMMYT offered crucial global resources to stop the spread of Ug99 and the avert the human catastrophe that would have resulted.”

An innovative wheat breeder known for his inexhaustible knowledge and attention to genetic detail, Singh helped establish the practice of “pyramiding” multiple rust-resistance genes into a single variety to confer immunity. This practice of adding complex resistance in a way that makes it difficult for evolving pathogens to overcome new varieties of wheat now forms the backbone of rust resistance breeding at CIMMYT and other national programs.

The global champion for durable resistance

Ravi joined CIMMYT in 1983 and was tasked by his supervisor, mentor and friend, the late World Food Prize Winner Sanjaya Rajaram, to develop wheat lines with durable resistance, said Hans Braun, former director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program.

“Ravi did this painstaking work — to combine recessive resistance genes — for two decades as a rust geneticist and, as leader of CIMMYT’s Global Spring Wheat Program, he transferred them at large scale into elite lines that are now grown worldwide,” Braun said. “Thanks to Ravi and his colleagues, there has been no major rust epidemic in the Global South for years, a cornerstone for global wheat security.”

Alison Bentley, Director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program, said that “Building on Ravi’s exceptional work throughout his career, deployment of durable rust resistance in widely adapted wheat germplasm continues to be a foundation of CIMMYT’s wheat breeding strategy.”

Revered for his determination and work ethic throughout his career, Singh has contributed to the development of 649 wheat varieties released in 48 countries, working closely with scientists at national wheat programs in the Global South. Those varieties today are sown on approximately 30 million hectares annually in nearly all wheat growing countries of southern and West Asia, Africa and Latin America. Of these varieties, 224 were developed directly under his leadership and are grown on an estimated 10 million hectares each year.

In his career Singh has authored 328 refereed journal articles and reviews, 32 book chapters and extension publications, and more than 80 symposia presentations. He is regularly ranked in the top 1% of cited researchers. The CIMMYT team that Singh leads identified and designated 22 genes in wheat for resistance or tolerance to stem rust, leaf rust, stripe rust, powdery mildew, barley yellow dwarf virus, spot blotch, and wheat blast, as well as characterizing various other important wheat genome locations contributing to durable resistance in wheat.

Singh’s impact as a plant breeder and steward of genetic resources over the past four decades has been extraordinary, according to Braun: “Ravi Singh can definitely be called the global champion for durable resistance.”

This piece by Matt Hayes was originally posted on the BGRI website.