Whole grains

The most recent dietary guidelines provided by the World Health Organization and other international food and nutrition authorities recommend that half our daily intake of grains should come from whole grains. But what are whole grains, what are their health benefits, and where can they be found?

What are whole grains?

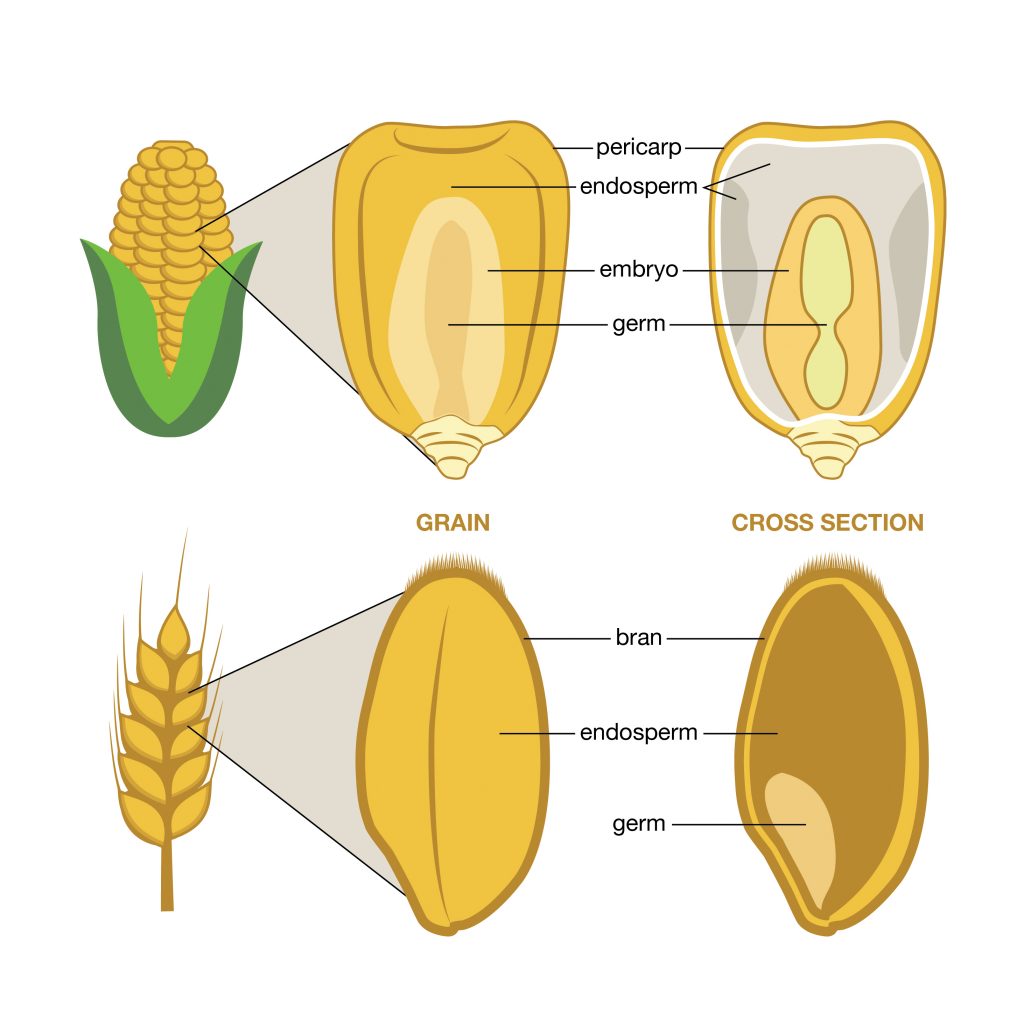

The grain or kernel of any cereal is made up of three edible parts: the bran, the germ and the endosperm.

Each part of the grain contains different types of nutrients.

- The bran is the multi-layered outer skin of the edible kernel. It is fiber-rich and also supplies antioxidants, B vitamins, minerals like zinc, iron, magnesium, and phytochemicals — natural chemical compounds found in plants that have been linked to disease prevention.

- The germ is the core of the seed where growth occurs. It is rich in lipids and contains vitamin E, as well as B vitamins, phytochemicals and antioxidants.

- The largest portion of the kernel is the endosperm, an interior layer that holds carbohydrates, protein and smaller amounts of vitamins and minerals.

A whole grain is not necessarily an entire grain.

The concept is mainly associated with food products — which are not often made using intact grains — but there is no single, accepted definition of what constitutes a whole grain once parts of it have been removed.

Generally speaking, however, a processed grain is considered “whole” when each of the three original parts — the bran, germ and endosperm — are still present in the same proportions as when the original one. This definition applies to all cereals in the Poaceae family such as maize, wheat, barley and rice, and some pseudocereals including amaranth, buckwheat and quinoa.

Wholegrain vs. refined and enriched grain products

Refined grain products differ from whole grains in that some or all of the outer bran layers are removed by milling, pearling, polishing, or degerming processes and are missing one or more of their three key parts.

For example, white wheat flour is prepared with refined grains that have had their bran and germ removed, leaving only the endosperm. Similarly, if a maize kernel is degermed or decorticated — where both the bran and germ are removed — it becomes a refined grain.

The main purpose of removing the bran and germ is technological, to ensure finer textures in final food products and to improve their shelf life. The refining process removes the variety of nutrients that are found in the bran and germ, so many refined flours end up being enriched — or fortified — with additional, mostly synthetic, nutrients. However, some components such as phytochemicals cannot be replaced.

Are wholegrain products healthier than refined ones?

There is a growing body of research indicating that whole grains offer a number of health benefits which refined grains do not.

Bran and fiber slow the breakdown of starch into glucose, allowing the body to maintain a steady blood sugar level instead of causing sharp spikes. Fibers positively affect bowel movement and also help to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular diseases, the incidence of type 2 diabetes, the risk of stroke, and to maintain an overall better colorectal and digestive health. There is also some evidence to suggest that phytochemicals and essential minerals — such as copper and magnesium — found in the bran and germ may also help protect against some cancers.

Despite the purported benefits, consumption of some wholegrain foods may be limited by consumer perception of tastes and textures. The bran in particular contains intensely flavored compounds that reduce the softness of the final product and may be perceived to negatively affect overall taste and texture. However, these preferences vary greatly between regions. For example, while wheat noodles in China are made from refined flour, in South Asia most wheat is consumed wholegrain in the form of chapatis.

Popcorn is another example of a highly popular wholegrain food. It is a high-quality carbohydrate source that, consumed naturally, is not only low in calories and cholesterol, but also a good source of fiber and essential vitamins including folate, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, pantothenic acid and vitamins B6, A, E and K. One serving of popcorn contains about 8% of the daily iron requirement, with lesser amounts of calcium, copper, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium and zinc.

Boiled and roasted maize commonly consumed in Africa, Asia and Latin America are other sources of wholegrain maize, as is maize which has been soaked in lime solution, or “nixtamalized.” Depending on the steeping time and method of washing the nixtamalized kernels, a portion of the grains used for milling could still be classed as whole.

Identifying wholegrain products

Whole grains are relatively easy to identify when dealing with unprocessed foods such as brown rice or oats. It becomes more complicated, however, when a product is made up of both whole and refined or enriched grains, especially as color is not an indicator. Whole wheat bread made using whole grains can appear white in color, for example, while multi-grain brown bread can be made primarily using refined flour.

In a bid to address this issue, US-based nonprofit consumer advocacy group the Whole Grains Council created a stamp designed to help consumers identify and select wholegrain products more easily. As of 2019, this stamp is used on over 13,000 products in 61 different countries.

However, whether a product is considered wholegrain or not varies widely between countries and individual agencies, with a lack of industry standardization meaning that products are labelled inconsistently. Words such as “fiber,” “multigrain” and even “wholegrain” are often used on packaging for products which are not 100% wholegrain. The easiest way to check a product’s wholegrain content is to look at the list of ingredients and see if the flours used are explicitly designated as wholegrain. These are ordered by weight, so the first items listed are those contained more heavily in the product.

As a next step, an ad-hoc committee led by the Whole Grain Initiative is due to propose specific whole grain quantity thresholds to help establish a set of common criteria for food labelling. These are likely to be applied worldwide in the event that national definitions and regulations are not standardized.

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.