How Crops to End Hunger is transforming CGIAR crop breeding from the ground up

When crop breeding succeeds, the impact is dramatic: improved varieties reach farmers, productivity increases, and resilience to climate change and disease improves. But breeding success doesn’t happen by chance. It relies on modern facilities, cutting-edge tools, and the ability to test and select for complex, evolving traits. That’s where Crops to End Hunger (CtEH) comes in. At CGIAR Science Week, the project team and beneficiaries demonstrated how.

A project designed for exponential impact

Launched in 2019, CtEH aimed to support the modernization of CGIAR’s crop breeding infrastructure, with support from GIZ, the Gates Foundation, the US government, DFID, and ACIAR. As it nears the end of the most recent two-year GIZ funding cycle, the project has made targeted investments in upgrading breeding station infrastructure, equipping them with advanced tools, building capacity across CGIAR and national breeding teams, and developing the foundational systems needed to accelerate the entire breeding process.

Supporting CGIAR Centers’ core functions

At CGIAR Science Week, Bram Govaerts, CIMMYT Director General, explained: “CtEH is crucial for implementing CIMMYT 2030 strategy. Support has increased our breeding capacity for maize, wheat, and newly added dryland crops that complement maize and wheat cropping systems.”

One example is the Groundnut Biotic Stress Screening Network, established with CtEH support. The network has strengthened the capacity of partners in Uganda and Malawi to screen for groundnut rosette disease; a devastating disease spread by aphids can result in 100% crop loss, with annual losses of over $150 million. The screening network will enable development of resistant varieties.

In Kenya, a $2.5 million worth infrastructure upgrade at the KALRO–CIMMYT Crop Research Facility in Kiboko, has accelerated breeding cycles. This investment is enabling the development of new varieties tailored to the needs of East African farmers. Drought-tolerant maize varieties developed through work in Kenya and Zimbabwe have expanded dramatically, from just 0.5 million hectares in 2010 to 8.5 million hectares across sub-Saharan Africa today.

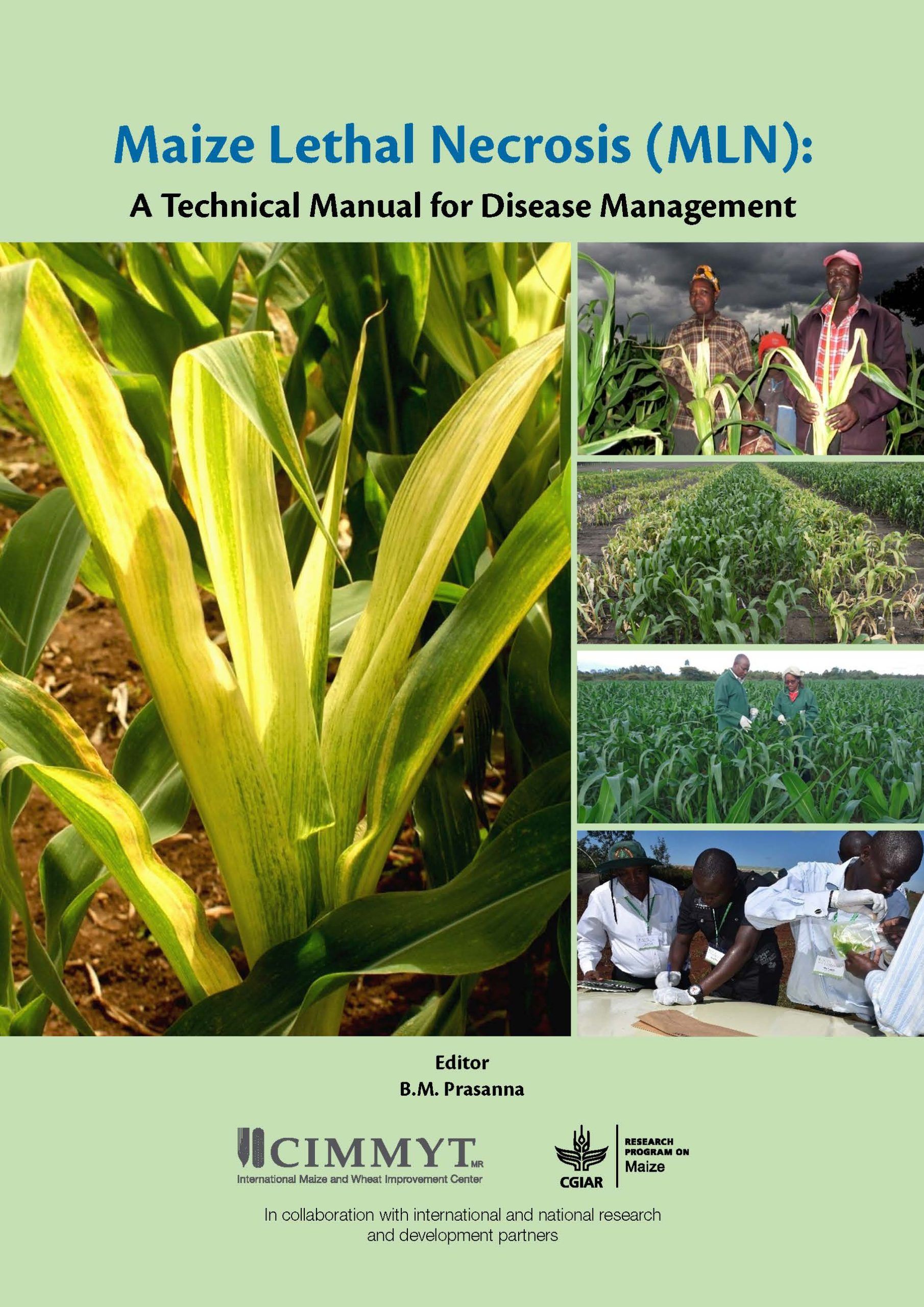

The Kiboko station is also a regional leader in pest and disease resistance. Its advanced screening capabilities for fall armyworm have led to the release of three tolerant maize hybrids, benefiting farmers in Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Sudan, and Ghana. The development of maize varieties resistant to maize lethal necrosis further demonstrates the station’s critical role in enhancing food security across the region.

Operational improvements: more than bricks and mortar

CtEH isn’t just about infrastructure; it’s also about operational transformation which profoundly change the breeding work. For instance, as Gustavo Teixeira explains, “The installation of reliable irrigation systems, one of CtEH’s key priorities, improves breeding efficiency in several ways. It enables off-season trials, allowing breeders to conduct multiple generations per year. It promotes plot control, ensuring uniformity across trial plots and data quality. Finally, it improves the ability to breed for drought tolerance.”

In Ghana, Maxwell Asante of CSIR-CRI described how CtEH brought crop-neutral upgrades that have encouraged teams to strategically plan and align resources, enabled cost attribution to specific breeding programs, improving accountability, and fostered cross-location collaboration by making centralized services possible.

These operational improvements are helping CGIAR and national systems move toward truly modern breeding programs that can operate with greater precision, speed, and coordination.

Building for regional collaboration and innovation

Bram Govaerts also emphasized that collaboration is central to the future of breeding, and that CtEH is helping to make that possible.

“Strategic collaborations enhance our impact by leveraging diverse resources and expertise, especially through public-private partnerships that scale research and technology transfer for agricultural transformation.”

Facilities and systems funded by CtEH are helping CGIAR foster cross-disciplinary innovation and strengthen ties with governments, donors, and technology companies. This makes it easier to bridge the gap between research and real-world application – exactly what’s needed to accelerate impact.

Empowering women in breeding

Infrastructure improvements under CtEH have considered inclusivity and gender equity.

Aparna Das, CIMMYT Technical Lead, explained that modernized stations have been upgraded to better support women in breeding roles – such as providing restrooms and expression rooms in remote research stations, often located far from urban centers, which help attract talent.

Why does this matter? Women breeders bring valuable perspectives, particularly in identifying gender-relevant traits, like cooking time, seed size, and ease of harvesting. Diverse, balanced breeding teams also tend to be more dynamic and innovative, leading to better science and more relevant products for farmers.

Targeting the right traits

Breeding for traits farmers need starts with the ability to test and measure those traits under real-world conditions. This can require specialized equipment.

Maxwell Asante emphasized that this is where CtEH makes a difference:

“Testing for traits is fundamental. And now, we’re not just selecting for yield – we’re breeding for disease resistance, climate resilience, cooking quality, and more. The only way to do this efficiently is through modern breeding infrastructure and processes.”

Modern breeding enables scientists to combine multiple traits in a single variety and identify the best candidates with greater accuracy and confidence. This is made possible through CtEH investments in equipment and data analytics, such as Bioflow, the CtEH-funded breeding analytics pipeline developed for CGIAR and its partners.

Long-term impact through smart design

What makes CtEH unique is its sustainability-by-design approach. The project was structured to build long-lasting capacity and to leverage investments from across CGIAR Initiatives, amplifying both the quality of upgrades and their outcomes.

Whether it’s enabling year-round trials, supporting new partnerships, or empowering a more diverse generation of breeders, CtEH is not just upgrading infrastructure, it’s also reshaping CGIAR and partners’ breeding.

As CGIAR continues to respond to climate, nutrition, and food security challenges, projects like CtEH are making sure we have the tools, systems, and people in place to breed for tomorrow – starting today.

To learn more about Crops to End Hunger, check out other stories here.