Unveiling the Nexus between Agrifood Systems and Climate Change: Harvesting insights from latest IPCC report

August 2 is Earth Overshoot Day 2023, which marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year.

“Climate change is already affecting agrifood systems,” said the director general of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Bram Govaerts. “Efforts to protect food and crop systems from things like rising temperatures and drought are part of the overall solution to reverse ecological overshoot; however, we must work hard to ensure these efforts are collaborative, inclusive and sustainable. We want to reach climate goals without compromising food security.”

To harmonize climate change mitigation efforts, CIMMYT and the CGIAR Climate Impact Platform jointly hosted a webinar on July 11, 2023, for relevant stakeholders to discuss the latest findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The IPCC is an organization of governments that are members of the United Nations and provides regular assessments of the risks of climate change and options for mitigation.

“Climate change in agrifood systems presents special challenges. There are adaptation challenges, but even more importantly, reducing emissions while also protecting the lives and livelihoods of smallholder farmers is a huge challenge that requires scientists and practitioners working together,” said Aditi Mukherji, director of the CGIAR Climate Impact Platform. “Action based on science is needed and IPCC and CGIAR came together in this webinar to present those challenges and solutions.”

The webinar summarized key findings from the IPCC on how climate change effects agrifood systems, including potential adaptation measures and strategies for mitigating the effects of climate change on agri-food systems, how food system management can be part of the solutions to mitigate climate change without compromising food security. Participants also identified potential collaborations and partnerships to implement IPCC recommendations.

“On this acknowledgement of Earth Overshoot Day, the IPCC report is an important milestone as we enact sustainable solutions to protect against climate change and work toward pulling back overshoot,” said Claudia Sadoff, the executive managing director of CGIAR. “All strategies must be under-pinned with reliable data to let us know what is happening now and also in the future.”

The webinar kicked off with presentations from Alex Ruane, co-Director of the GISS Climate Impacts Group, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and IPCC author, Mukherji, and Jim Skea, IPCC Co-Chair.

Challenges Ahead

Ruane examined the current impacts of climate change on agrifood systems and presented findings regarding future effects; knowledge that can help guide priority-setting among relevant stakeholders.

He detailed the perilous state of agrifood systems, as they need to sustainably increase production to provide healthy food for growing populations, adapt to climate change and ongoing climate extremes, mitigate emissions from agricultural lands and maintain financial incentives for agriculture.

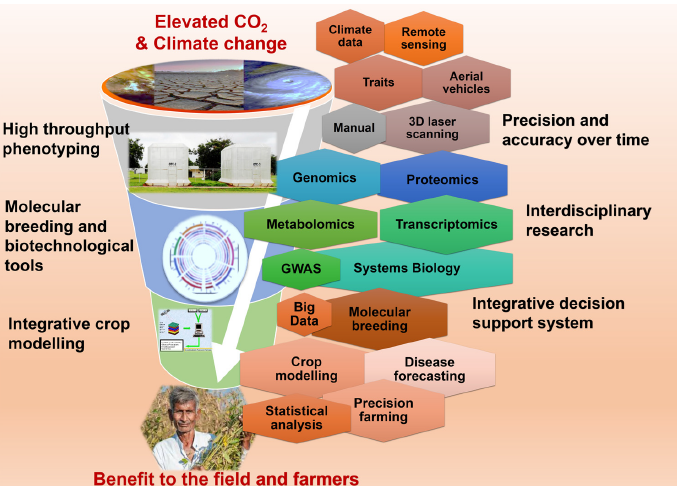

Answering those challenges requires the development of models that can track all potential climate drivers. A co-development process with robust data-sharing is vital to provide context for risk management and planning for climate adaptation and mitigation.

Adaptation

Mukherji examined current adaptation efforts within agrifood systems. The IPCC data showed that the people and regions seeing the most adverse effects of climate change have also emitted the fewest amount of greenhouse gases.

There are multiple opportunities for scaling up climate action. CGIAR is working on such responses in the areas of efficient livestock systems, improved cropland management, water use, agroforestry, sustainable aquaculture and more.

Maladaptation can be avoided by flexible, inclusive, long-term planning and implementation of adaptation actions, with benefits shared by many sectors and systems.

Mitigation

Skea investigated the demand and supply side synthesis: land use change and rapid land use intensification have supported increased food production and food demand has increased as well.

He also summarized the IPCC findings regarding land use mitigation efforts, like reforestation (restoring trees in an area where their population has been reduced), afforestation (establishing trees in an area where there has not been recent tree cover) and improved overall forest management, quantifying each action on agrifood systems.

Panel discussion

Moderated by Tek Sapkota, CIMMYT/ CGIAR and IPCC scientist, with panelists Kaveh Zahedi, director of the Office of Climate Change, Biodiversity and Environment, FAO; Jyotsna Puri, associate vice-president, International Fund for Agricultural Development; Jacobo Arango, thematic leader, Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT/CGIAR and IPCC author; Louis Verchot, principal scientist, Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT/CGIAR and IPCC author, and Jim Skea, the panel discussed the IPCC findings and examined crucial areas for targeted development.

Earth Overshoot Day is hosted and calculated by the Global Footprint Network, an international research organization that provides decision-makers with a menu of tools to help the human economy operate within Earth’s ecological limits.