A sustainable solution to micronutrient deficiency

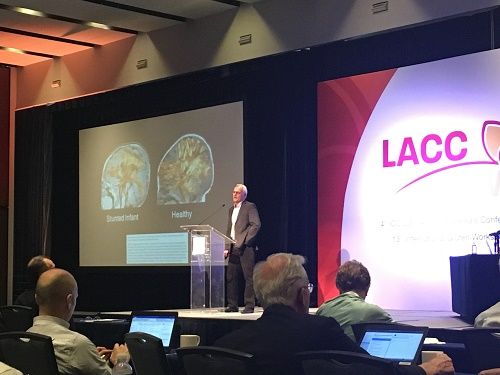

Zinc deficiency affects one third of the global population; vitamin A deficiency is a prevalent public health issue in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This includes countries like Nepal, where alarming rates of micronutrient deficiency contribute to a host of health problems across different age groups, such as stunting, weakened immune systems, and increased maternal and child mortality.

In the absence of affordable options for dietary diversification, food fortification, or nutrient supplementation, crop biofortification remains one of the most sustainable solutions to reducing micronutrient deficiency in the developing world.

After a 2016 national micronutrient status survey highlighted the prevalence of zinc and vitamin A deficiency among rural communities in Nepal’s mountainous western provinces, a team of researchers from the Nepal Agricultural Research Council and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) proposed a study to assess the yield performance of zinc and provitamin A enriched maize varieties.

Focusing on the river basin area of Karnali Province — where maize is the staple food crop for most people – they conducted two different field trials using an alpha lattice design to identify zinc and provitamin A biofortified maize genotypes consistent and competitive in performance over the contrasting seasons of February to July and August to February.

The study, recently published in Plants, compared the performance of newly introduced maize genotypes with local varieties, focusing on overall agro-morphology, yield, and micronutrient content. In addition to recording higher levels of kernel zinc and total carotenoid, it found that several of the provitamin A and zinc biofortified genotypes exhibited greater yield consistency across different environments compared to the widely grown normal maize varieties.

The results suggest that these genotypes could be effective tools in combatting micronutrient deficiency in the area, thus reducing hidden hunger, as well as enhancing feed nutrient value for the poultry sector, where micronutrient rich maize is highly desired.

“One in three children under the age of five in Nepal and half of the children in the study area are undernourished. Introduction and dissemination of biofortified maize seeds and varieties will help to mitigate the intricate web of food and nutritional insecurity, especially among women and children,” said AbduRahman Beshir, CIMMYT’s seed systems specialist for Asia and the co-author of the publication. Strengthening such products development initiatives and enhancing quality seed delivery pathways will foster sustainable production and value chains of biofortified crops, added Beshir.

Read the study: Zinc and Provitamin A Biofortified Maize Genotypes Exhibited Potent to Reduce Hidden-Hunger in Nepal

Cover photo: Farm worker Bharat Saud gathers maize as it comes out of a shelling machine powered by 4WT in Rambasti, Kanchanpur, Nepal. (Photo: Peter Lowe/CIMMYT)