Building trust, bridging divides: How Zambia’s digital champions are paving the way for inclusive farming

In Zambia’s Southern Province, CIMMYT’s Atubandike[1] initiative is reshaping agricultural extension – moving beyond traditional top-down, one-size-fits-all models that have historically favored the well-resourced farmers. Instead, Atubandike promotes a more inclusive, demand-driven model that centers the voices of all farmers, regardless of gender, age, literacy level, or economic status. This shift is driven by a ‘phygital’ platform that blends the strengths of in-person support with the efficiency of mobile technology.

At the heart of Atubandike’s phygital platform are 84 local digital champions (DCs), half of whom are women, and 42% are under the age of 35. Selected by their communities, these champions embody the demographic shift that represents the future of agriculture. They are not external experts; but trusted peers and neighbors who serve as vital links between digital agricultural platforms and the people who need them most: the farmers. Their credibility, rooted in shared experience and local knowledge, is what enables them to build trust and drive meaningful change.

While mobile technology holds immense potential to sustainably boost agricultural productivity[2], many farmers remain digitally excluded. Barriers such as low literacy, limited phone access and entrenched social norms continue to hinder widespread engagement with digital advisory services [3]. That’s where the DCs step in – not only to introduce new tools, but to help dismantle these barriers; ensuring that no one is left behind.

A foundation of trust

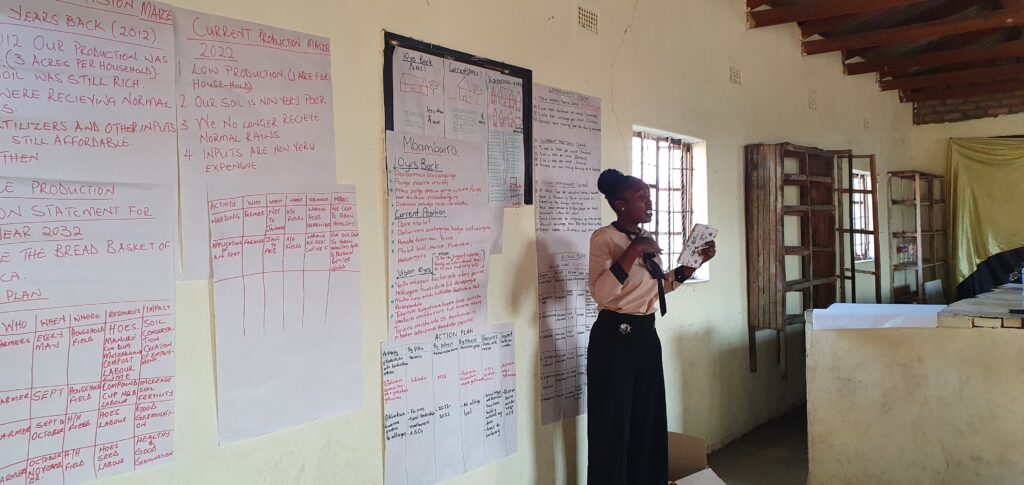

In October and November 2024, Digital Champions from 14 Zambian communities gathered for a two-day, in-person workshop. This training, which complemented previous digital skills sessions, focused on co-developing two pivotal strategies: (1) building trust with farmers through effective communication and (2) addressing the complex gender, diversity, and inclusion (GDI) challenges affecting the DCs as well as the farmers they support.

Why begin with trust? Because trust is foundational to meaningful engagement. For farmers to adopt new climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices and digital platforms like Atubandike, they must have confidence-both in the messengers and the technology itself. This insight shaped the training design, which was grounded [4] in empirical studies and further contextualized through in-depth interviews with 36 farmers in November 2023. The resulting curriculum emphasized care, communication, and competence – not only to help DCs build trust as messengers, but also to support farmers in using their phones with confidence. By strengthening both interpersonal and digital trust, DCs play a critical role in closing the gap between farmers and the tools that can transform their livelihoods.

The training was designed and delivered through a dialogical approach encouraging open conversation and engagement by the participants throughout the learning process. Through role plays, group discussions, and real-life scenario analysis, DCs engaged deeply with the material, facilitated peer-to-peer learning, and developed a strong sense of ownership and confidence in applying their new skills.

The session explored what it means to connect meaningfully with farmers and as one female participant shared, “the interactive nature of the training, with role plays and real-life scenarios, have given me the confidence and desire to go on and apply what I have learned in the field.”

Trust-building exercises, such as active listening and respectful communication, fostered empathy. These practices not only enhanced the DC’s ability to effectively engage with farmers – they reinforced the values that form the bedrock of inclusive community engagement.

Challenging norms and building inclusion

Trust, however, is only part of the story. True inclusion requires confronting the systemic biases that have long shaped rural agricultural systems. In Zambia, deeply rooted cultural norms often determine who gets to speak, who leads and whose voice is heard. Women, youth and the elderly frequently face significant barriers to leadership roles and are often excluded from participating in community dialogues. and their opinions often pushed aside.

To address this, the Gender, Diversity, and Inclusion (GDI) curriculum tackled exclusion head-on. Rooted in insights from 13 community engagement meetings held in mid-2024, the course content reflected the lived realities of local communities. These were not abstract concepts-they were honest, community-led conversations about barriers people face and the solutions they envision.

One male Digital Champion reflected: “In our communities, farming tasks like milking, planting, and weeding are often tied to gender. But moving forward, we will encourage our fellow farmers to see these as shared responsibilities.”

Female DCs also shared their personal experiences of exclusion and resilience. “Being a woman, I have faced challenges in earning recognition as a leader,’ one participant shared. “But this training has given me confidence to lead in my community.” Another young mother brought her newborn to the training – an act that symbolized the very inclusion the program espouses. “You didn’t just teach about inclusion,” she said expressing her gratitude to CIMMYT. “You demonstrated it, making sure I had support for my child so that I could focus and learn.”

As the training came to a close, the DCs moved beyond theory. Together, they co-created practical strategies to address cultural resistance, promote inclusive participation, and support marginalized farmers in accessing essential agricultural resources. Empowered by new skills and a strong sense of ownership, they left not only informed but ready to act.

From insight to impact

Some of the most meaningful learning moments came from lived experience. In one session, a DC recounted how a shift in approach – simply listening – changed her relationship with a skeptical farmer. “He told me that no one had really listened to him before. That act marked the moment we started working together.”

Breakthroughs emerged during the sessions on gender dynamics. Initially met with hesitation, the role-play exercises and open dialogue gradually opened space for reflection and growth. Male DCs began to recognize the value of women’s perspectives, while female participants found renewed confidence to speak up and voice their opinions. These seemingly small shifts in mindset marked important steps toward broader social change, grounded in empathy, understanding and mutual respect.

The training also brought logistical challenges, such as the high cost of reaching remote farmers, limited phone access, and the digital divine within some households. In response, the Atubandike program introduced practical solutions, including airtime and data allowances for DCs, encouraging people to share their phones or advising farmers to borrow handsets from trusted neighbors.

To sustain this momentum, CIMMYT launched regular one-on-one check-in calls with each DC. These touchpoints offer mentorship, reflection and tailored support as DCs continue to embed trust-building and inclusive practices into their everyday work.

Looking ahead: a story of empowerment

As the sessions concluded, a new energy and sense of purpose took hold. DCs left not only with new skills, but with a clear commitment to act. They pledged to attend and host regular community meetings, conduct home visits for farmers unable to attend meetings and use WhatsApp groups to foster ongoing peer learning and collaboration.

This is just the beginning. The next chapter is about turning plans into practice ensuring that the digital revolution in agriculture is truly inclusive and leaves no farmer behind.

The story of digital champions in Zambia is one of empowerment. It is not only about their growth as leaders, but also about the transformation they are catalyzing in their communities. As they challenge social norms, build trust, and amplify unheard voices, they are shaping a more inclusive and resilient agricultural future.

[1]Atubandike, meaning “let’s chat” in Tonga, a local language spoken in Zambia’s Southern Province.

[2] Fabregas, Raissa, Michael Kremer, and Frank Schilbach. 2019. “Realizing the Potential of Digital Development: The Case of Agricultural Advice.” Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay3038.

[3] Sterling, R. (2021, January 14). “Why Women Aren’t Using Your Ag App.” Agrilinks. https://agrilinks.org/post/why-women-arent-using-your-ag-app

[4] Examples include: Buck, Steven, and Jeffrey Alwang. 2011. “Agricultural Extension, Trust, and Learning: Results from Economic Experiments in Ecuador.” Agricultural Economics 42 (6): 685–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00547.x. Greene, Jessica, and Christal Ramos. 2021. “A Mixed Methods Examination of Health Care Provider Behaviors That Build Patients’ Trust.” Patient Education and Counseling 104 (5): 1222–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.003.