Balanced fertilizer application boosts smallholder incomes

Agriculture is largely feminized in Nepal, where over 80% of women are employed in the sector. As a result of the skills gap caused by male out-migration, many women farmers are now making conscious efforts to learn techniques that can help improve yields and generate greater income — such as balanced fertilizer application — with support from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Studies have shown that many farmers lack knowledge of fertilizer management, but balanced fertilizer application using the right ratio of nutrients is key to helping crops thrive Through the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, CIMMYT researchers are working towards promoting precision nutrient management through multiple trials and demonstrations in farmers’ fields.

Through this initiative, Dharma Devi Chaudhary, a smallholder farmer from Kailali district, has been able to increase her annual earnings by adopting balanced fertilizer application in cauliflower cultivation — a key cash crop for the winter season in Nepal’s Terai region.

Her inspiration to use micronutrients such as boron came from the results she witnessed during a CIMMYT-supported demonstration conducted on her land in 2018. During the demonstration, Chaudhary learned the principles of the four ‘Rs’ of nutrient stewardship: the right rate, the right time, the right source and the right placement of fertilizers. She became familiar with different types of fertilizer and the amount to be used, as well as the appropriate time and place to apply urea top-dressing, diammonium phosphate (DAP) and muriate of potash (MoP) for optimal utilization by the plant.

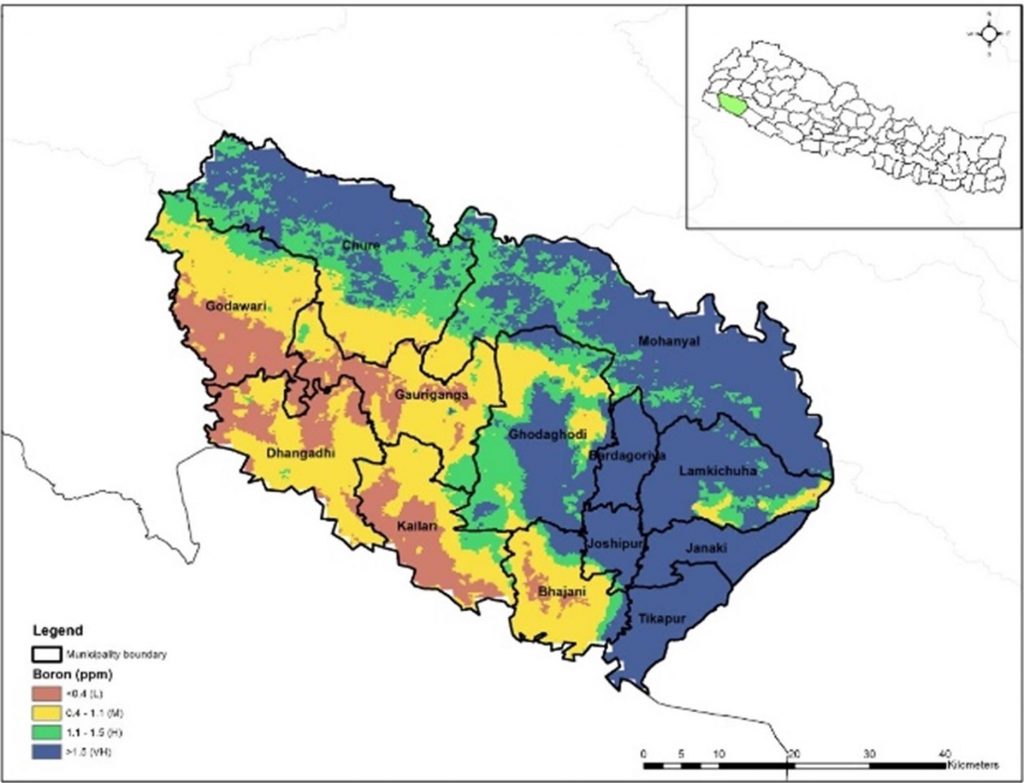

Chaudhary also learned how boron application can increase crop yields while helping prevent plant diseases, especially in cauliflower, where boron deficiency can lead to a disorder known as ‘dead heart’ and cause significant yield loss. This is particularly useful knowledge for farmers in Nepal, where the boron content in soil is generally low.

Benefitting from best practices

Cauliflower is cultivated on 615 hectares of land across Kailali and produces a yield of 15 tons per hectare — far less than the potential yield of 35-40 tons. As a standard practice, farmers in the area have been applying nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (NPK) at a ratio of 27: 27.6: 9 kilograms per hectare and three tons of farmyard manure per hectare. During a CIMMYT-led demonstration on a small parcel of land, Chaudhary observed that balanced fertilizer application yielded about 64% more than when using her traditional practices, fetching her an income of $180 that season compared to her usual $109.

Following this demonstration, Chaudhary decided to independently cultivate cauliflower on a plot of 500 square meters, where she applied farmyard manure two weeks before transplantation and then used DAP, MOP, boron and zinc as a basal application during transplanting. She also applied urea in split doses, first at 25 days and then 50 days after transplantation. Using this technique, Chaudhary was able to yield 46 tons of cauliflower per hectare, nearly twice as much as was yielded by farmers using traditional practices. As a result, she was able to generate an income increase of $800 for her household, compared to the previous season’s earnings.

“I was able to buy education resources, clothing and more food supplies for my children with the additional income I earned from selling cauliflower last year,” said Chaudhary. “Learning about the benefits of using micronutrients is essential for smallholder farmers like me who are looking for ways to improve their farming business.”

Smallholder farmers tend to be risk averse, which can make technology adoption difficult. However, on-farm demonstrations help reduce the risks farmers perceive and facilitate new technology adoption easily by exhibiting encouraging results.

Chaudhary now serves as a lead farmer at Janasewa Krishak Multi-purpose Cooperative and supports the organization by disseminating knowledge on balanced fertilizer management practices to hundreds of farmers in her community. After seeing the impact of adopting the recommended techniques, the use of balanced fertilizer is reaping benefits for other farmers in her district, helping them achieve better income from higher crop yields and maintain soil fertility in their area.