Seed production innovations, conservation agriculture and partnerships are key for Africa’s food security

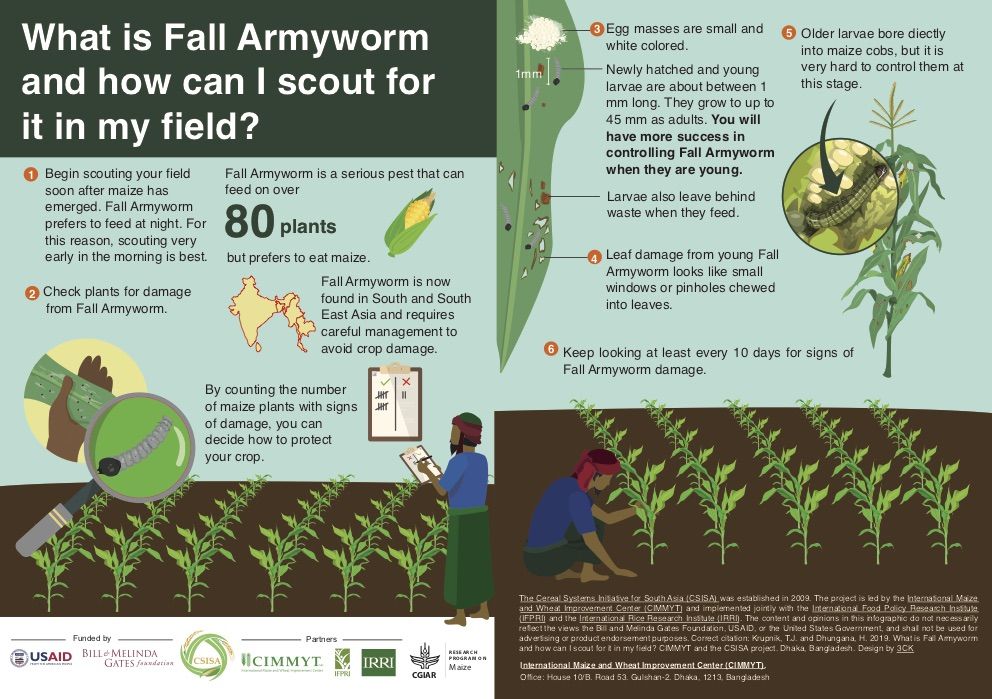

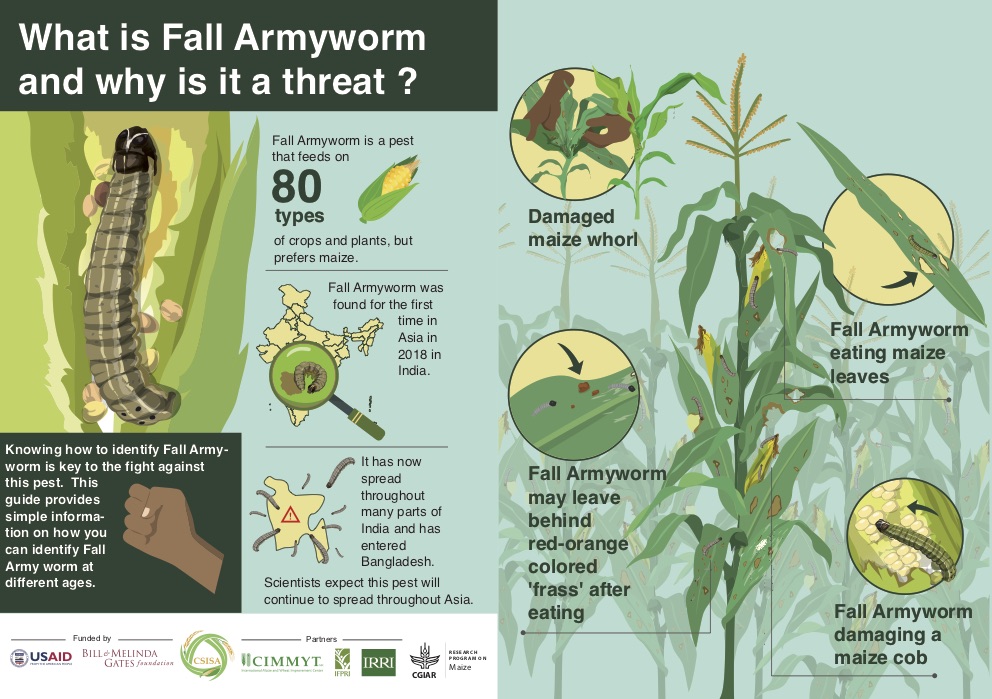

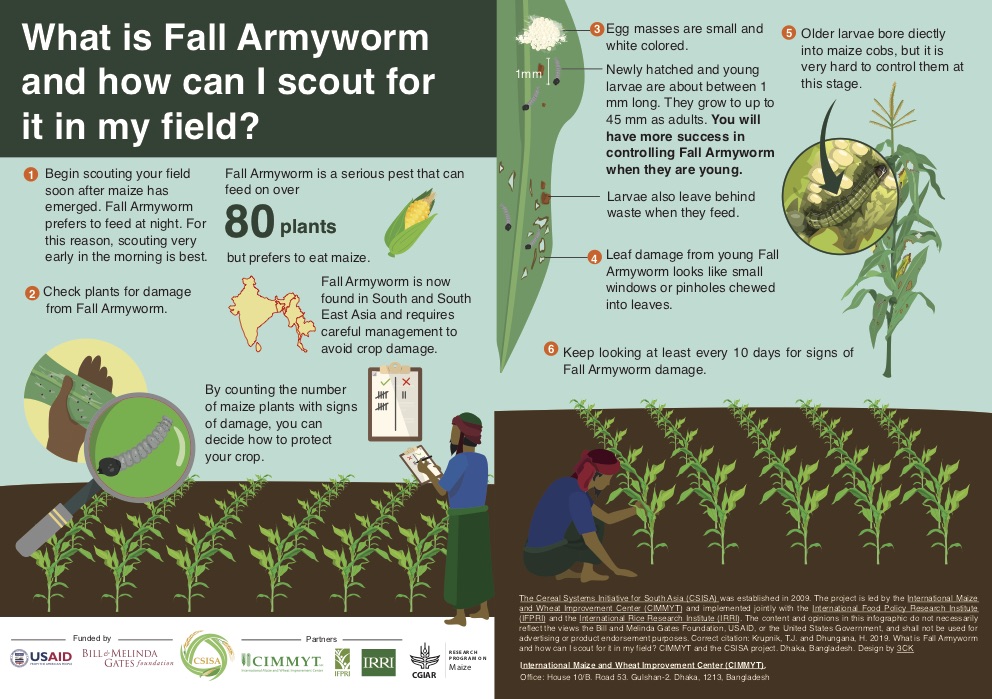

Members of the International Maize Improvement Consortium Africa (IMIC – Africa) and other maize and wheat research partners discovered the latest innovations in seed and agronomy at Embu and Naivasha research stations in Kenya on August 27 and 28, 2019. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Kenya Agriculture & Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) held their annual partner field days to present sustainable solutions for farmers to cope with poor soils, a changing climate and emerging diseases and pests, such as wheat rust, maize lethal necrosis or fall armyworm.

Versatile seeds and conservation agriculture offer farmers yield stability

“Maize is food in Kenya. Wheat is also gaining importance for our countries in eastern Africa,” KALRO Embu Center Director, Patrick Gicheru, remarked. “We have been collaborating for many years with CIMMYT on maize and wheat research to develop and disseminate improved technologies that help our farmers cope against many challenges,” he said.

Farmers in Embu, like in most parts of Kenya, faced a month delay in the onset of rains last planting season. Such climate variability presents a challenge for farmers in choosing the right maize varieties. During the field days, CIMMYT and KALRO maize breeders presented high-yielding maize germplasm adapted to diverse agro-ecological conditions, ranging from early to late maturity and from lowlands to highlands.

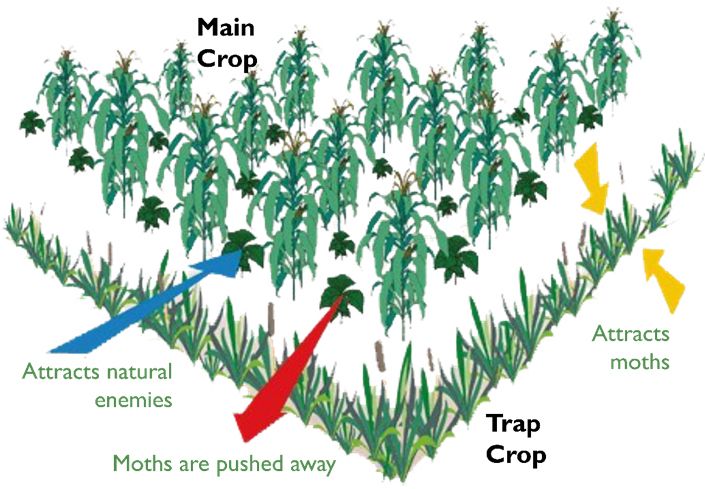

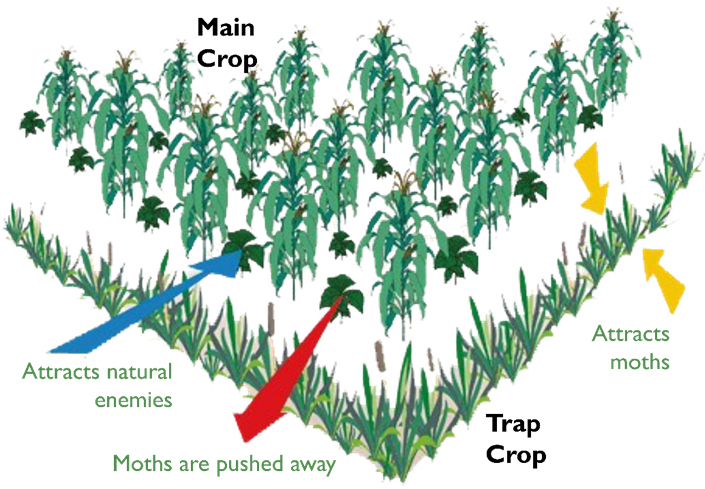

João Saraiva, from the Angolan seed company Jardins d’Ayoba, said having access to the most recent improved maize germplasm is helpful for his young seed company to develop quality seeds adapted to farmers’ needs. He is looking for solutions against fall armyworm, as the invasive species is thriving in the Angolan tropical environment. He was interested to hear about CIMMYT’s progress to identify promising maize lines resistant to the caterpillar. Since fall armyworm was first observed in Africa in 2016, CIMMYT has screened almost 1,200 inbred lines and 2,900 hybrids for tolerance to fall armyworm.

“Hopefully, we will be developing and releasing the first fall armyworm-tolerant hybrids by the first quarter of 2020,” announced B.M. Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Programme and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE).

“Through continuous innovations to build varieties that perform well despite dry spells, heat waves or disease outbreak, maize scientists have been able to deliver significant yield increases each year across various environments,” explained Prasanna. “This genetic gain race is important to respond to growing grain demands despite growing climate risks and declining soil health.”

Berhanu Tadesse, maize breeder at the Ethiopian Institute for Agricultural Research (EIAR), was highly impressed by the disease-free, impeccable green maize plants at Embu station, remembering the spotted and crippled foliage during a visit more than a decade ago. This was “visual proof of constant progress,” he said.

For best results, smallholder farmers should use good agronomic practices to conserve water and soil health. KALRO agronomist Alfred Micheni demonstrated different tillage techniques during the field tour including the furrow ridge, which is adapted to semi-arid environments because it retains soil moisture.

Innovations for a dynamic African seed sector

A vibrant local seed industry is needed for farmers to access improved varieties. Seed growers must be able to produce pure, high-quality seeds at competitive costs so they can flourish in business and reach many smallholder farmers.

Double haploid technology enables breeders to cut selection cycles from six to two, ultimately reducing costs by one third while ensuring a higher level of purity. Sixty percent of CIMMYT maize lines are now developed using double haploid technology, an approach also available to partners such as the Kenyan seed company Western Seeds.

The Seed Production Technology for Africa (SPTA) project, a collaboration between CIMMYT, KALRO, Corteva Agriscience and the Agricultural Research Council, is another innovation for seed companies enabling cheaper and higher quality maize hybrid production. Maize plants have both female and male pollen-producing flowers called tassels. To produce maize hybrids, breeders cross two distinct female and male parents. Seed growers usually break the tassels of female lines manually to avoid self-pollination. SPTA tested a male sterility gene in Kenya and South Africa, so that female parents did not produce pollen, avoiding a detasseling operation that damages the plant. It also saves labor and boosts seed yields. Initial trial data showed a 5 to 15% yield increase, improving the seed purity as well.

World-class research facilities to fight new and rapidly evolving diseases

The KALRO Naivasha research station has hosted the maize lethal necrosis (MLN) quarantine and screening facility since 2013. Implementing rigorous phytosanitary protocols in this confined site enables researchers to study the viral disease first observed in Africa 2011 in Bomet country, Kenya. Working with national research and plant health organizations across the region and the private sector, MLN has since been contained.

A bird’s eye view of the demonstration plots is the best testimony of the impact of MLN research. Green patches of MLN-resistant maize alternate with yellow, shrivelled plots. Commercial varieties are susceptible to the disease that can totally wipe out the crop, while new MLN-resistant hybrids yield five to six tons per hectare. Since the MLN outbreak in 2011, CIMMYT has released 19 MLN-tolerant hybrids with drought-tolerance and high-yielding traits as well.

A major challenge to achieving food security is to accelerate the varietal replacement on the market. CIMMYT scientists and partners have identified the lengthy and costly seed certification process as a major hurdle, especially in Kenya. The Principal Secretary of the State Department for Research in the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries, Hamadi Boga, pledged to take up this issue with the Kenya Plant and Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS).

“Such rapid impact is remarkable, but we cannot rest. We need more seed companies to pick up these new improved seeds, so that our research reaches the maximum number of smallholders,’’ concluded Prasanna.