Harnessing econometric and statistical tools to support climate-resilient agriculture

Globally, climate extremes are adversely affecting agricultural productivity and farmer welfare. Farmers’ lack of knowledge about adaptation options may further exacerbate the situation. In the context of South Asia, which is home to rural farm-based economies with smallholder populations, tailored adaptation options are crucial to safeguarding the region’s agriculture in response to current and future climate challenges. These resilience strategies encompass a range of risk reducing practices such as changing the planting date, Conservation Agriculture, irrigation, stress-tolerant varieties, crop diversification, and risk transfer mechanisms, e.g., crop insurance. Practices such as enterprise diversification and community water conservation are also potential sector-specific interventions.

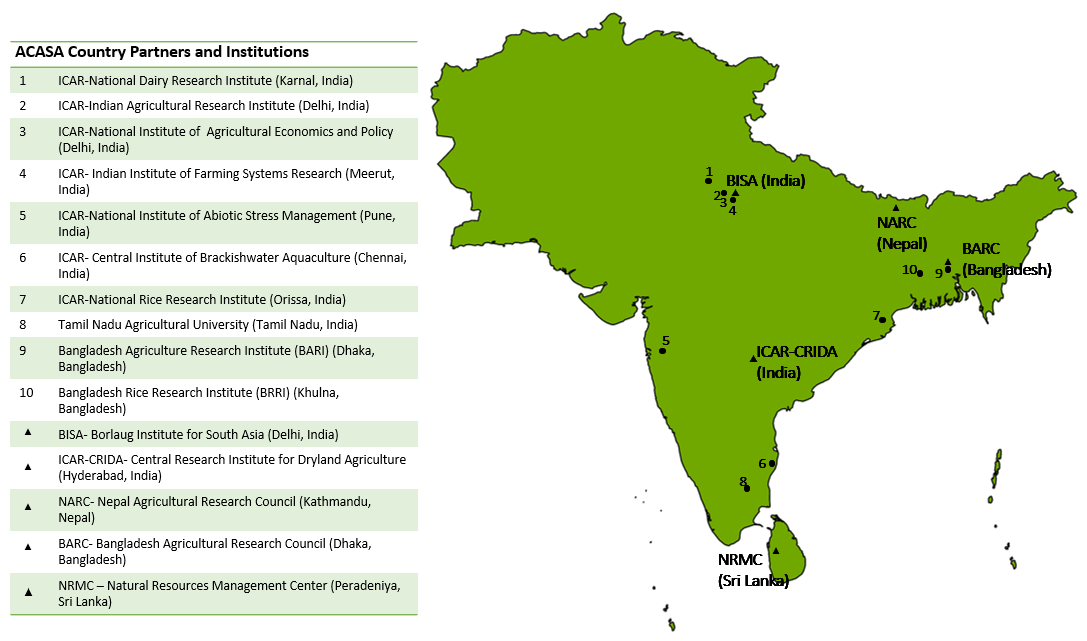

Atlas of Climate Adaptation in South Asian Agriculture (ACASA) aims to identify hazard-linked adaptation options and prioritize them at a granular geographical scale. While doing so, it is paramount to consider the suitability of adaptation options from a socioeconomic lens which varies across spatial and temporal dimensions. Further, calculation of scalability parameters such as economic, environmental benefit, and gender inclusivity for prioritized adaptation are important to aid climatic risk management and developmental planning in the subcontinent. Given the credibility of econometric and statistical methods, the key tenets of the approach that are being applied in ACASA are worth highlighting.

Evaluating the profitability of adaptation options

Profitability is among the foremost indicators for the feasible adoption of any technology. The popular metric of profitability evaluation is benefit-to-cost ratio. This is a simple measure based on additional costs and benefits because of adopting new technology. A benefit-to-cost ratio of more than one is considered essential for financial viability. Large-scale surveys such as cost of cultivation and other household surveys can provide cost estimates for limited adaptation options. Given the geographical and commodity spread, ACASA must resort to the meta-analysis of published literature or field trials for adaptation options. For example, a recent paper by International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) based on meta-analysis shows that not all interventions result in a win-win situation with improvements in both tradable and non-tradable outcomes. While no-till wheat, legumes, and integrated nutrient management result in an advantageous outcome, there are trade-offs between the tradable and non-tradable ecosystem services in the cases of directed seed rice, organic manure, and agroforestry2.

Quantification of adaptation options to mitigate hazards

Past studies demonstrate the usefulness of econometric methods when analyzing the effectiveness of adaptation options such as irrigation, shift in planting time, and crop diversification against drought and heat stress in South Asia. Compared to a simple cost-benefit approach, the adaptation benefits of a particular technology under climatic stress conditions can be ascertained by comparing it with normal weather conditions. The popular methods in climate economics literature are panel data regression and treatment-based models. Subject to data availability, modern methods of causal estimation, and machine learning can be used to ascertain the robust benefits of adaptation options. Such studies, though available in literature, have compared limited adaptation options. A study by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-National Institute of Agricultural Economics and Policy Research (ICAR-NIAP), based on ‘Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households’ of National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), concluded that though crop insurance and irrigation effectively improve farm income and reduce farmers’ exposure to downside risk, irrigation is more effective than crop insurance1.

Statistical models for spatial interpolation of econometric estimates

Since ACASA focuses on gridded analysis, an active area of statistical application is the spatial interpolation or downscaling of results to a more granular scale. Many indicators used for risk characterization are available at coarser geographical units or points from surveys. Kriging is a spatial interpolation method where there is no observed data. Apart from spatial interpolation of observed indicators, advanced Kriging methods can be potentially used to interpolate or predict the estimates of the econometric model.

ACASA’s approach involves prioritizing adaptation options based on suitability, scalability, and gender inclusivity. Econometric and statistical methods play a crucial role in evaluating the profitability and effectiveness of various adaptation strategies from real world datasets. Despite challenges such as limited observational data and integration of econometric and statistical methods, ACASA can facilitate informed decision-making in climate risk management and safeguard agricultural productivity in the face of climatic hazards.

1 Birthal PS, Hazrana J, Negi DS and Mishra A. 2022. Assessing benefits of crop insurance vis-a-vis irrigation in Indian agriculture. Food Policy 112:102348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102348

2 Kiran Kumara T M, Birthal PS, Chand D and Kumar A. 2024. Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services of Selected Interventions in Agriculture in India. IFPRI Discussion Paper 02250, IFPRI-South Asia Regional Office, New Delhi.

Blog written by Prem Chand, ICAR-NIAP, India and Kaushik Bora, BISA-CIMMYT, India