Conservation agriculture key in meeting UN Sustainable Development Goals

An international team of scientists has provided a sweeping new analysis of the benefits of conservation agriculture for crop performance, water use efficiency, farmers’ incomes and climate action across a variety of cropping systems and environments in South Asia.

The analysis, published today in Nature Sustainability, is the first of its kind to synthesize existing studies on conservation agriculture in South Asia and allows policy makers to prioritize where and which cropping systems to deploy conservation agriculture techniques. The study uses data from over 9,500 site-year comparisons across South Asia.

According to M.L. Jat, a principal scientist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and first author of the study, conservation agriculture also offers positive contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals of no poverty, zero hunger, good health and wellbeing, climate action and clean water.

“Conservation agriculture is going to be key to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals,” echoed JK Ladha, adjunct professor at the University of California, Davis, and co-author of the study.

Scientists from CIMMYT, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the University of California, Davis, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and Cornell University looked at a variety of agricultural, economic and environmental performance indicators — including crop yields, water use efficiency, economic return, greenhouse gas emissions and global warming potential — and compared how they correlated with conservation agriculture conditions in smallholder farms and field stations across South Asia.

Results and impact on policy

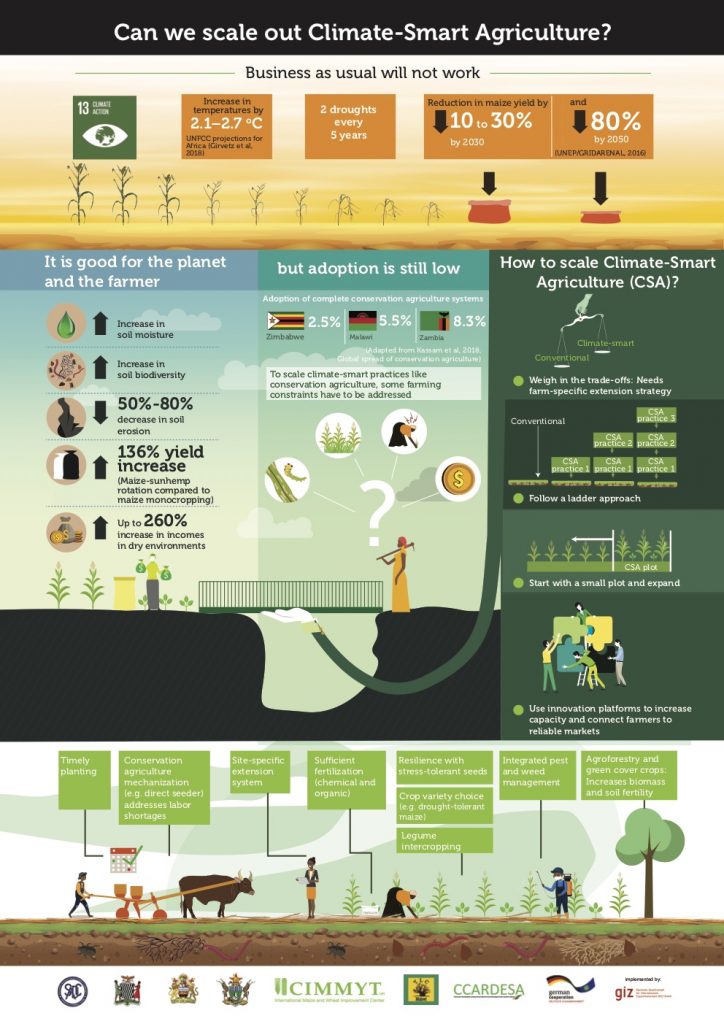

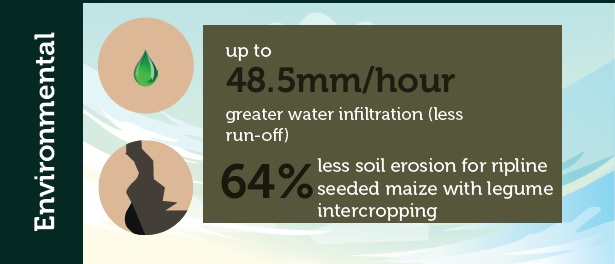

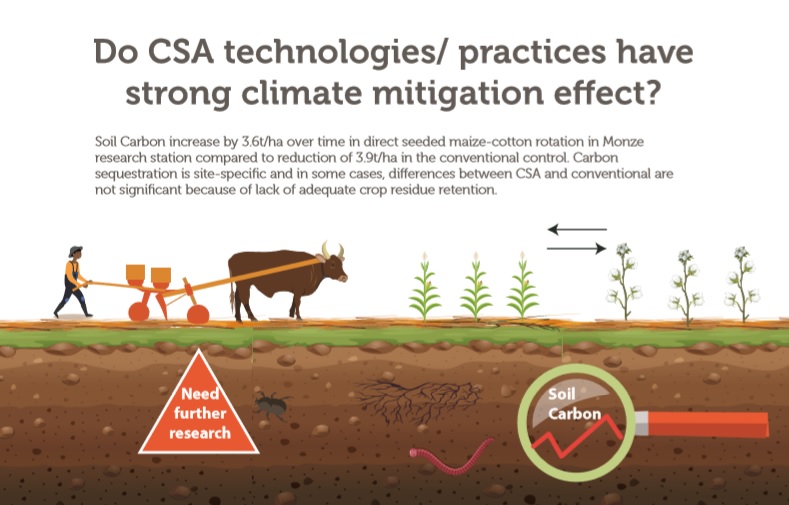

Researchers found that many conservation agriculture practices had significant benefits for agricultural, economic and environmental performance indicators, whether implemented separately or together. Zero tillage with residue retention, for example, had a mean yield advantage of around 6%, provided farmers almost 25% more income, and increased water use efficiency by about 13% compared to conventional agricultural practices. This combination of practices also was shown to cut global warming potential by up to 33%.

This comes as good news for national governments in South Asia, which have been actively promoting conservation agriculture to increase crop productivity while conserving natural resources. South Asian agriculture is known as a global “hotspot” for climate vulnerability.

“Smallholder farmers in South Asia will be impacted most by climate change and natural resource degradation,” said Trilochan Mohapatra, Director General of ICAR and Secretary of India’s Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE). “Protecting our natural resources for future generations while producing enough quality food to feed everyone is our top priority.”

“ICAR, in collaboration with CIMMYT and other stakeholders, has been working intensively over the past decades to develop and deploy conservation agriculture in India. The country has been very successful in addressing residue burning and air pollution issues using conservation agriculture principles,” he added.

With the region’s population expected to rise to 2.4 billion, demand for cereals is expected to grow by about 43% between 2010 and 2050. This presents a major challenge for food producers who need to produce more while minimizing greenhouse gas emissions and damage to the environment and other natural resources.

“The collaborative effort behind this study epitomizes how researchers, policy-makers, and development practitioners can and should work together to find solutions to the many challenges facing agricultural development, not only in South Asia but worldwide,” said Jon Hellin, leader of the Sustainable Impact Platform at IRRI.

Related publications:

Conservation agriculture for sustainable intensification in South Asia.

Interview opportunities:

M.L. Jat, Principal Scientist and Cropping Systems Agronomist, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)

For more information, or to arrange interviews, contact:

Rodrigo Ordóñez, Communications Manager, CIMMYT. r.ordonez@cgiar.org

Acknowledgements:

Funders of this work include the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the Government of India and the CGIAR Research Programs on Wheat Agri-Food Systems (CRP WHEAT) and Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

About CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.

Climate mitigation or resilience?

Climate mitigation or resilience?  “Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.

“Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.