Saving water and time

“I wonder why I never considered using drip irrigation for all these years,” says Michael Duri, a 35-year-old farmer from Ward 30, Nyanga, Zimbabwe, as he walks through his 0.5-hectare plot of onions and potatoes. “This is by far the best method to water my crops.”

Duri is one of 30 beneficiaries of garden drip-kits installed by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), an implementing partner under the Program for Growth and Resilience (PROGRESS) consortium, managed by the Zimbabwe Resilience Building Fund (ZRBF).

“In June 2020, I installed the drip kit across 0.07 hectares and quickly realized how much water I was saving through this technology and the reduced amount of physical effort I had to put in,” explains Duri. By September, he had invested in two water tanks and more drip lines to expand the area under drip irrigation to 0.5 hectares.

Water woes

Zimbabwe’s eastern highland districts like Nyanga are renowned for their diverse and abundant fresh produce. Farming families grow a variety of crops — potatoes, sugar beans, onions, tomatoes, leafy vegetables and garlic — all year round for income generation and food security.

Long poly-pipes lining the district — some stretching for more than 10 kilometers — use gravity to transport water from the mountains down to the villages and gardens. However, in the last five-to-ten years, increasing climate-induced water shortages, prolonged dry spells and high temperatures have depleted water reserves.

To manage the limited resources, farmers access water based on a rationing schedule to ensure availability across all areas. Often during the lean season, water volumes are insufficient for effectively irrigating the vegetable plots in good time, which leads to moisture stress, inconsistent irrigation and poor crop performance. Reports of cutting off or diverting water supply among farmers are high despite the local council’s efforts to schedule water distribution and access across all areas. “When water availability is low, it’s not uncommon to find internal conflicts in the village as households battle to access water resources,” explains Grace Mhande, an avid potato producer in Ward 22.

Climate-proofing gardens

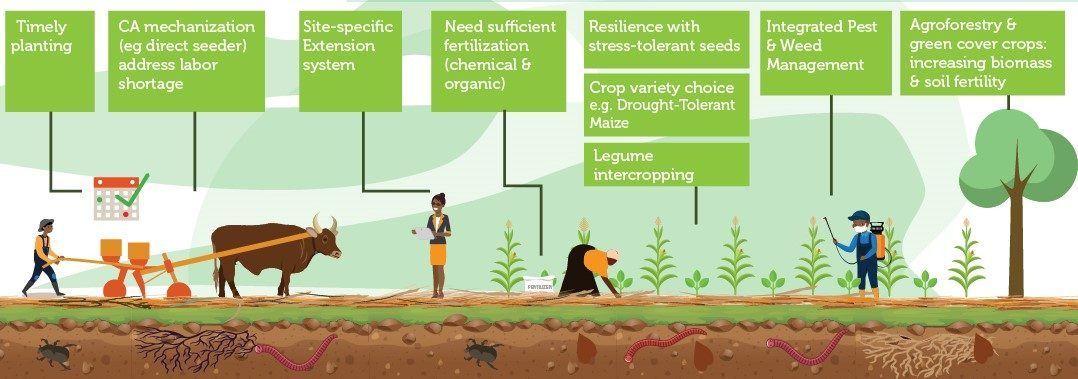

Traditionally, flood, drag hose, bucket and sprinkler systems have been used as the main irrigation methods. However, according to Raymond Nazare, an engineer from the University of Zimbabwe, these traditional irrigation designs “waste water, are laborious, require the services of young able-bodied workers and use up a lot of time on the part of the farmers.”

Prudence Nyanguru, who grows tomatoes, potatoes, cabbages and sugar beans in Ward 30, says the limited number of sprinklers available for her garden meant she previously had to irrigate every other day, alternating the sprinkler and hose pipe while spending more than five hours to complete an average 0.05-hectare plot.

“Whereas before I would spend six hours shifting the sprinklers or moving the hose, I now just switch on the drip and return in about two or three hours to turn off the lines,” says Nyanguru.

The drip technology is also helping farmers in Nyanga adapt to climate change by providing efficient water use, accurate control over water application, minimizing water wastage and making every drop count.

“With the sprinkler and flood systems, we noticed how easily the much-needed fertile top soil washed away along with any fertilizer applied,” laments Vaida Matenhei, another farmer from Ward 30. Matenhei now enjoys the simple operation and steady precision irrigation from her drip-kit installation as she monitors her second crop of sugar beans.

Frédéric Baudron, a systems agronomist at CIMMYT, observes that Zimbabwe has a long history of irrigation, but this has mostly tended to be large-scale. “This means either expensive pivots owned by large-scale commercial farmers — a minority of the farming population in Zimbabwe as in much of sub-Saharan Africa — or capital-intensive irrigation schemes shared by a multitude of small-scale farmers, often poorly managed because of conflicts amongst users,” he says. A similar pattern can be seen with mechanization interventions, where Zimbabwe continues to rely on large tractors when smaller, and more affordable, machines would be more adapted to most farmers in the country.

“Very little is done to promote small-scale irrigation,” explains Baudron. “However, an installation with drip kits and a small petrol pump costs just over $1 per square meter.”

A disability-inclusive technology

The design of the drip-kit intervention also focused on addressing the needs of people with disabilities. At least five beneficiaries have experienced the limitations to full participation in farming activities as a result of physical barriers, access challenges and strenuous irrigation methods in the past.

For 37-year-old Simon Makanza from Ward 22, for example, his physical handicap made accessing and carrying water for his home garden extremely difficult. The installation of the drip-kit at Makanza’s homestead garden has created a barrier-free environment where he no longer grapples with uneven pathways to fetch water, or wells and pumps that are heavy to operate.

“I used to walk to that well about 500 meters away to fetch water using a bucket,” he explains. “This was painstaking given my condition and by the time I finished, I would be exhausted and unable to do any other work.”

The fixed drip installation in his plot has transformed how he works, and it is now easier for Makanza to operate the pump and switches for the drip lines with minimal effort.

Families living with people with disabilities are also realizing the advantages of time-saving and ease of operation of the drip systems. “I don’t spend all day in the field like I used to,” says George Nyamakanga, whose brother Barnabas who has a psychosocial disability. “Now, I have enough time to assist and care for my brother while producing enough to feed our eight-member household.”

By extension, the ease of operation and efficiency of the drip-kits also enables elderly farmers and the sick to engage in garden activities, with direct benefits for the nutrition and incomes of these vulnerable groups.

Scaling for sustained productivity

Since the introduction of the drip-kits in Nyanga, more farmers like Duri are migrating from flood and sprinkler irrigation and investing in drip irrigation technology. From the 30 farmers who had drip-kits installed, three have now scaled up after witnessing the cost-effective, labor-saving and water conservation advantages of drip irrigation.

Dorcas Matangi, an assistant research associate at CIMMYT, explains that use of drip irrigation ensures precise irrigation, reduces disease incidence, and maximal utilization of pesticides compared to sprinklers thereby increasing profitability of the farmer. “Although we are still to evaluate quantitatively, profit margin indicators on the ground are already promising,” she says.

Thomas Chikwiramadara and Christopher Chinhimbiti are producing cabbages on their shared plot, pumping water out of a nearby river. One of the advantages for them is the labor-saving component, particularly with weed management. Because water is applied efficiently near the crop, less water is available for the weeds in-between crop plants and plots with drip irrigation are thus far less infested with weeds than plots irrigated with buckets or with flood irrigation.

“This drip system works well especially with weed management,” explains Chinhimbiti. “Now we don’t have to employ any casual labor to help on our plot because the weeds can be managed easily.”

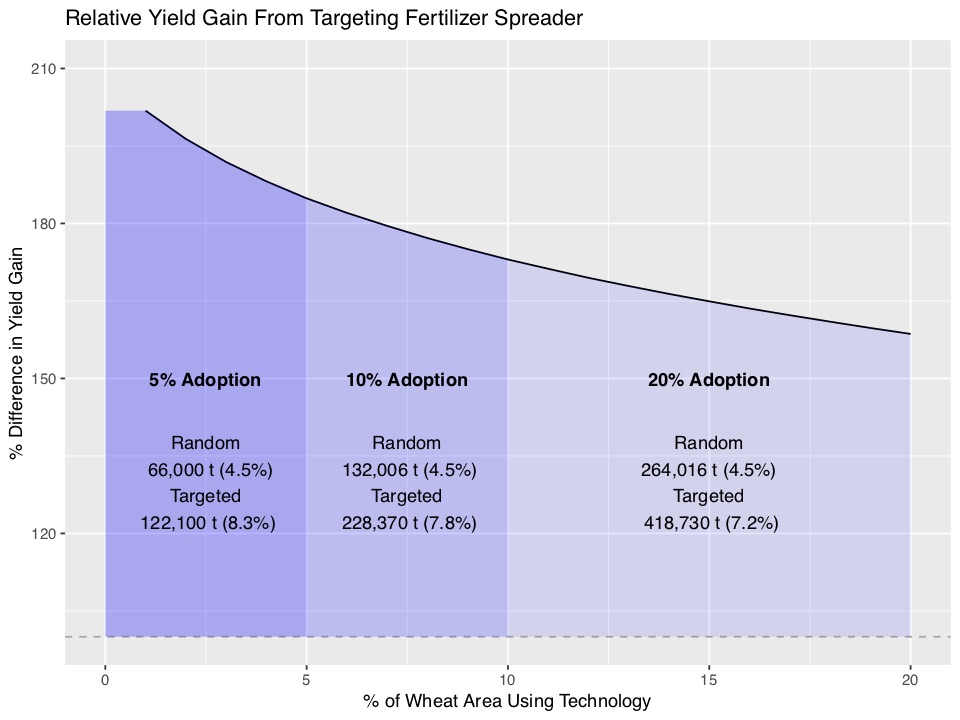

Climate mitigation or resilience?

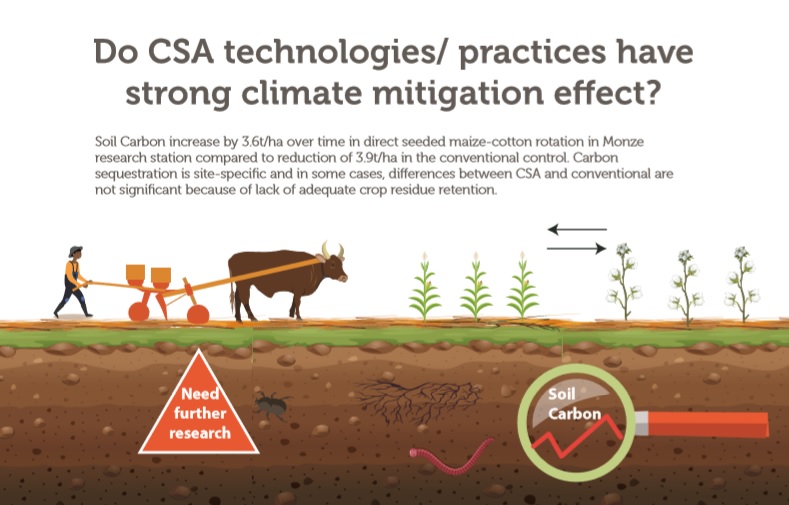

Climate mitigation or resilience?  “Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.

“Science is important to build up solid evidence of the benefits of a healthy soil and push forward much-needed policy interventions to incentivize soil conservation,” Thierfelder states.