Blast and rust forecast

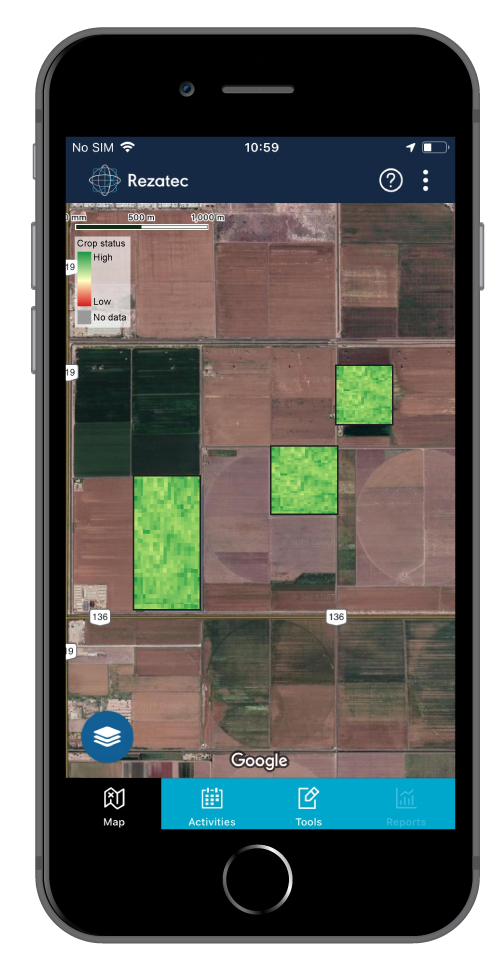

An early warning system set to deliver wheat disease predictions directly to farmers’ phones is being piloted in Bangladesh and Nepal by interdisciplinary researchers.

Experts in crop disease, meteorology and computer science are crunching data from multiple countries to formulate models that anticipate the spread of the wheat rust and blast diseases in order to warn farmers of likely outbreaks, providing time for pre-emptive measures, said Dave Hodson, a principal scientist with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) coordinating the pilot project.

Around 50,000 smallholder farmers are expected to receive improved disease warnings and appropriate management advisories through the one-year proof-of-concept project, as part of the UK Aid-funded Asia Regional Resilience to a Changing Climate (ARRCC) program.

Early action is critical to prevent crop diseases becoming endemic. The speed at which wind-dispersed fungal wheat diseases are spreading through Asia poses a constant threat to sustainable wheat production of the 130 million tons produced in the region each year.

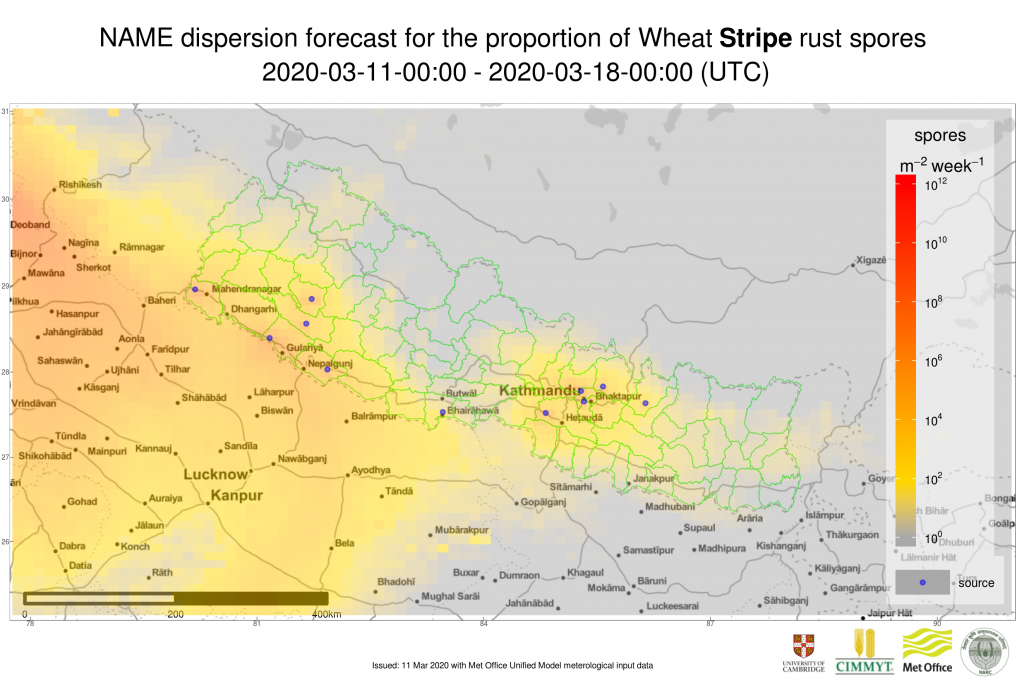

“Wheat rust and blast are caused by fungal pathogens, and like many fungi, they spread from plant to plant — and field to field — in tiny particles called spores,” said Hodson. “Disease strain mutations can overcome resistant varieties, leaving farmers few choices but to rely on expensive and environmentally-damaging fungicides to prevent crop loss.”

“The early warning system combines climate data and epidemiology models to predict how spores will spread through the air and identifies environmental conditions where healthy crops are at risk of infection. This allows for more targeted and optimal use of fungicides.”

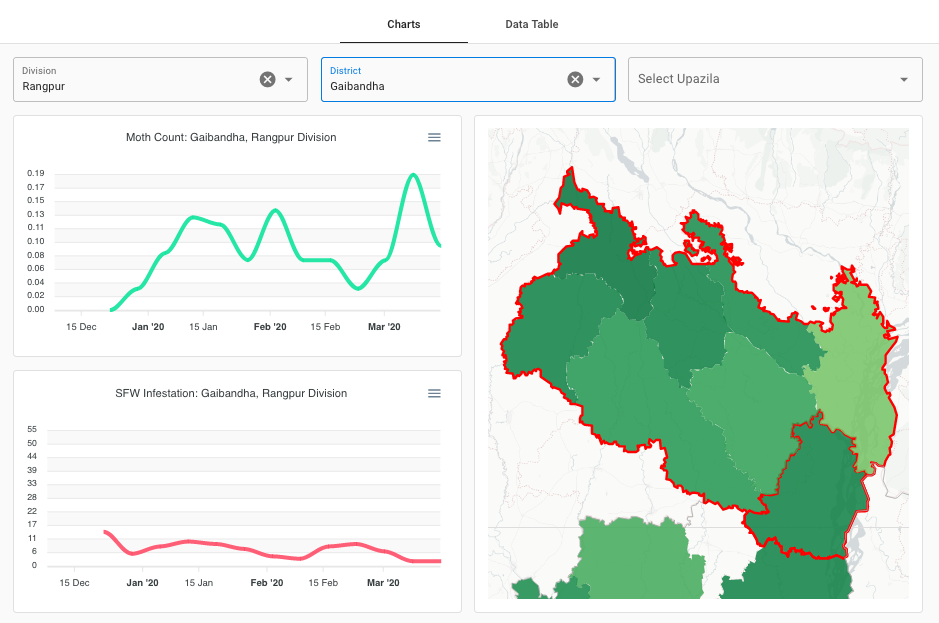

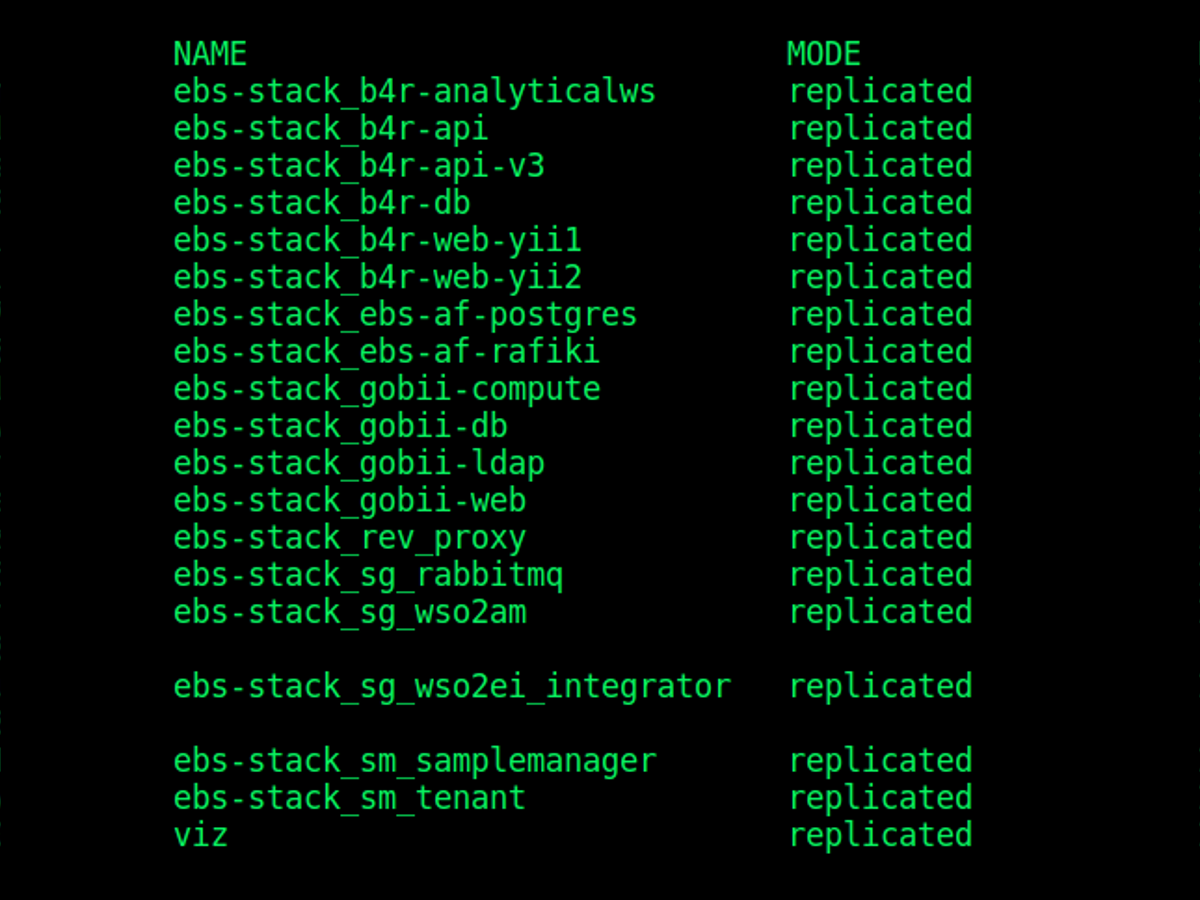

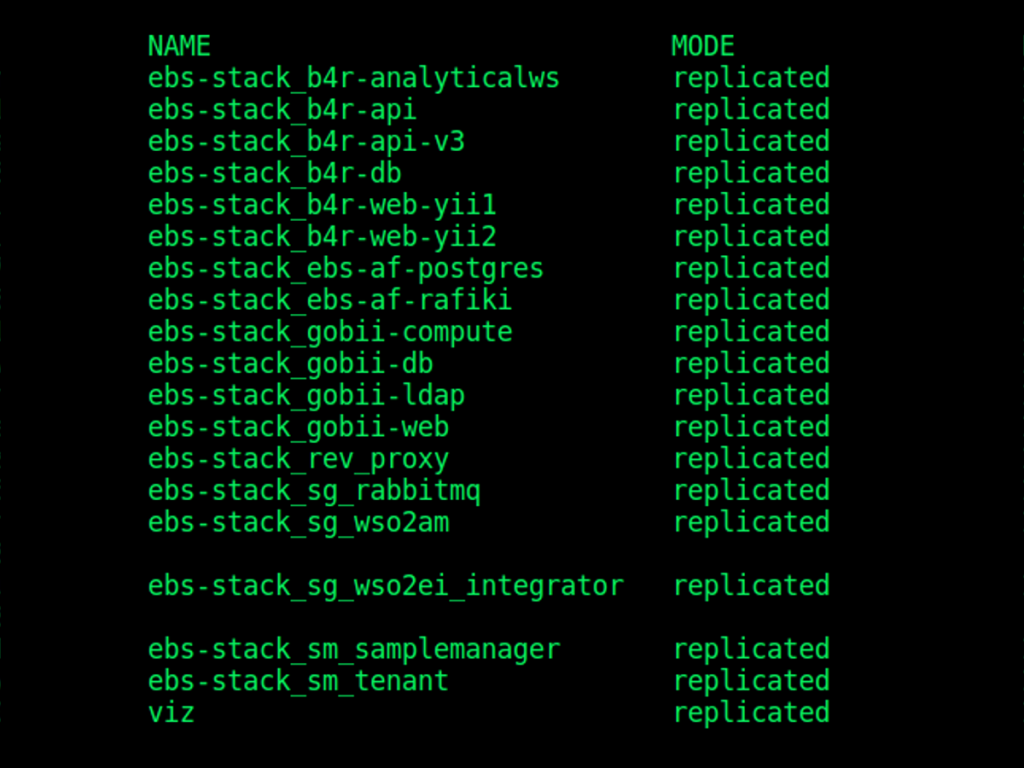

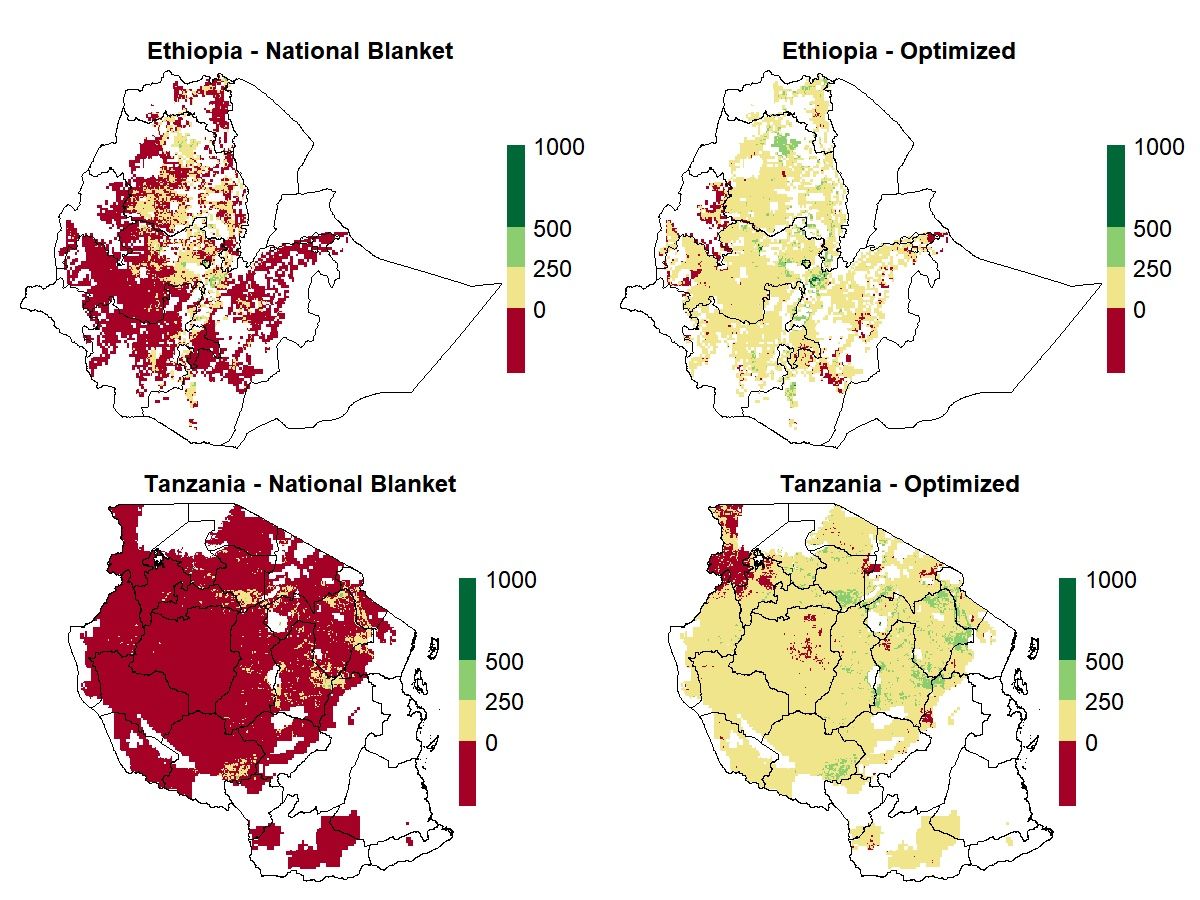

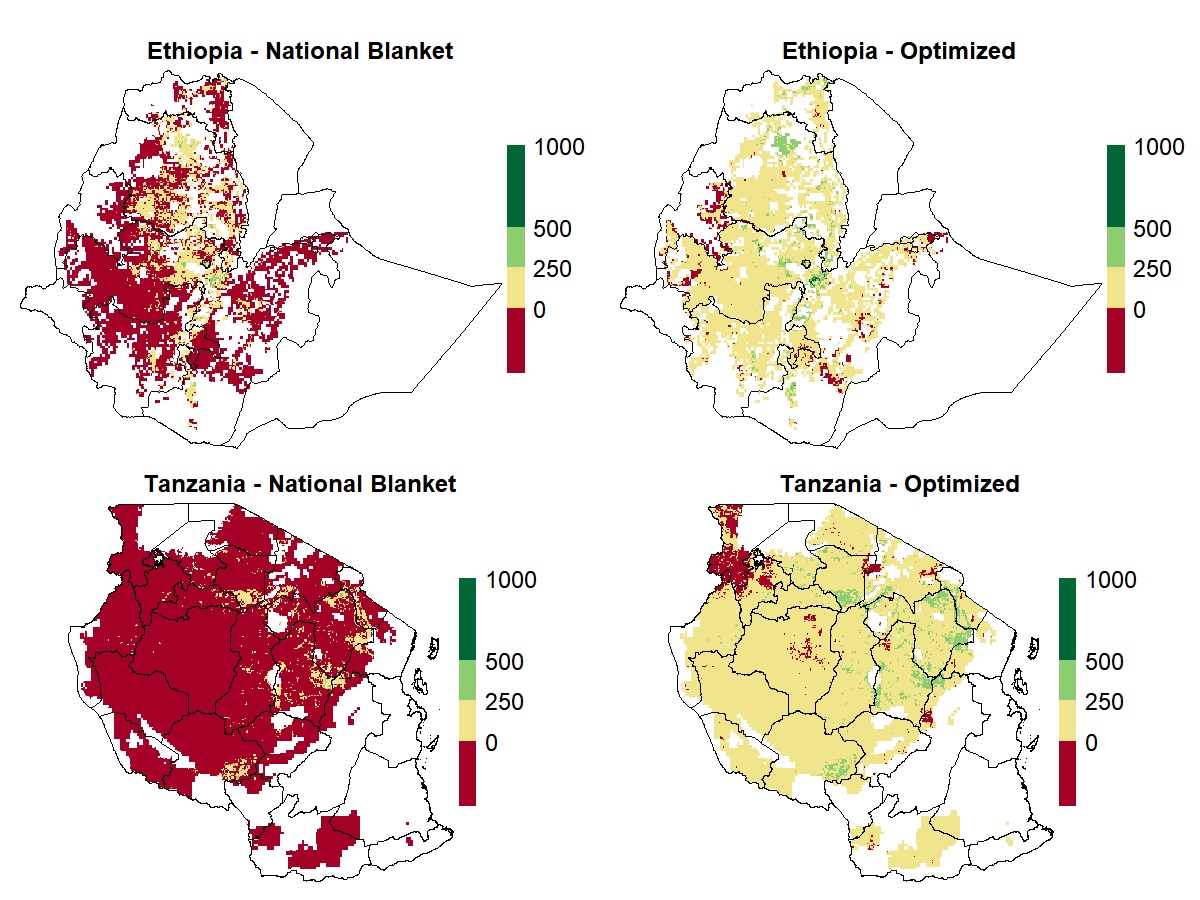

The system was first developed in Ethiopia. It uses weather information from the Met Office, the UK’s national meteorological service, along with field and mobile phone surveillance data and disease spread modeling from the University of Cambridge, to construct and deploy a near real-time early warning system.

Initial efforts focused on adapting the wheat stripe and stem rust model from Ethiopia to Bangladesh and Nepal have been successful, with field surveillance data appearing to align with the weather-driven disease early warnings, but further analysis is ongoing, said Hodson.

“In the current wheat season we are in the process of comparing our disease forecasting models with on-the-ground survey results in both countries,” the wheat expert said.

“Next season, after getting validation from national partners, we will pilot getting our predictions to farmers through text-based messaging systems.”

CIMMYT’s strong partnerships with governmental extension systems and farmer associations across South Asia are being utilized to develop efficient pathways to get disease predictions to farmers, said Tim Krupnik, a CIMMYT Senior Scientist based in Bangladesh.

“Partnerships are essential. Working with our colleagues, we can validate and test the deployment of model-derived advisories in real-world extension settings,” Krupnik said. “The forecasting and early warning systems are designed to reduce unnecessary fungicide use, advising it only in the case where outbreaks are expected.”

Local partners are also key for data collection to support and develop future epidemiological modelling, the development of advisory graphics and the dissemination of information, he explained.

The second stage of the project concerns the adaptation of the framework and protocols for wheat blast disease to improve existing wheat blast early warning systems already pioneered in Bangladesh.

Strong scientific partnership champions diversity to achieve common goals

The meteorological-driven wheat disease warning system is an example of effective international scientific partnership contributing to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, said Sarah Millington, a scientific manager at Atmospheric Dispersion and Air Quality Group with the Met Office.

“Diverse expertise from the Met Office, the University of Cambridge and CIMMYT shows how combined fundamental research in epidemiology and meteorology modelling with field-based disease observation can produce a system that boosts smallholder farmers’ resilience to major agricultural challenges,” she said.

The atmospheric dispersion modeling was originally developed in response to the Chernobyl disaster and since then has evolved to be able to model the dispersion and deposition of a range of particles and gases, including biological particles such as wheat rust spores.

“The framework together with the underpinning technologies are transferable to forecast fungal disease in other regions and can be readily adapted for other wind-dispersed pests and disease of major agricultural crops,” said Christopher Gilligan, head of the Epidemiology and Modelling Group at the University of Cambridge.

Fungal wheat diseases are an increasing threat to farmer livelihoods in Asia

While there has been a history of wheat rust disease epidemics in South Asia, new emerging strains and changes to climate pose an increased threat to farmers’ livelihoods. The pathogens that cause rust diseases are continually evolving and changing over time, making them difficult to control.

Stripe rust threatens farmers in Afghanistan, India, Nepal and Pakistan, typically in two out of five seasons, with an estimated 43 million hectares of wheat vulnerable. When weather conditions are conducive and susceptible cultivars are grown, farmers can experience losses exceeding 70%.

Populations of stem rust are building at alarming rates and previously unseen scales in neighboring regions. Stem rust spores can spread across regions on the wind; this also amplifies the threat of incursion into South Asia and the ARRCC program’s target countries, underscoring the very real risk that the disease could reemerge within the subcontinent.

The devastating wheat blast disease, originating in the Americas, suddenly appeared in Bangladesh in 2016, causing wheat crop losses as high as 30% on a large area, and continues to threaten South Asia’s vast wheat lands.

In both cases, quick international responses through CIMMYT, the CGIAR research program on Wheat (WHEAT) and the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative have been able to monitor and characterize the diseases and, especially, to develop and deploy resistant wheat varieties.

The UK aid-funded ARRCC program is led by the Met Office and the World Bank and aims to strengthen weather forecasting systems across Asia. The program is delivering new technologies and innovative approaches to help vulnerable communities use weather warnings and forecasts to better prepare for climate-related shocks.

The early warning system uses data gathered from the online Rust Tracker tool, with additional fieldwork support from the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), funded by USAID and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, both coordinated by CIMMYT.