Inspiring millennials to focus on food security: The power of mentorship

As part of their education, students worldwide learn about the formidable challenges their generation faces, including food shortages, climate change, and degrading soil health. Mentors and educators can either overwhelm them with reality or motivate them by real stories and showing them that they have a role to play. Every year the World Food Prize lives out the latter by introducing high school students to global food issues at the annual Borlaug Dialogue, giving them an opportunity to interact with “change agents” who address food security issues. The World Food Prize offers some students an opportunity to intern at an international research center through the Borlaug-Ruan International Internship program.

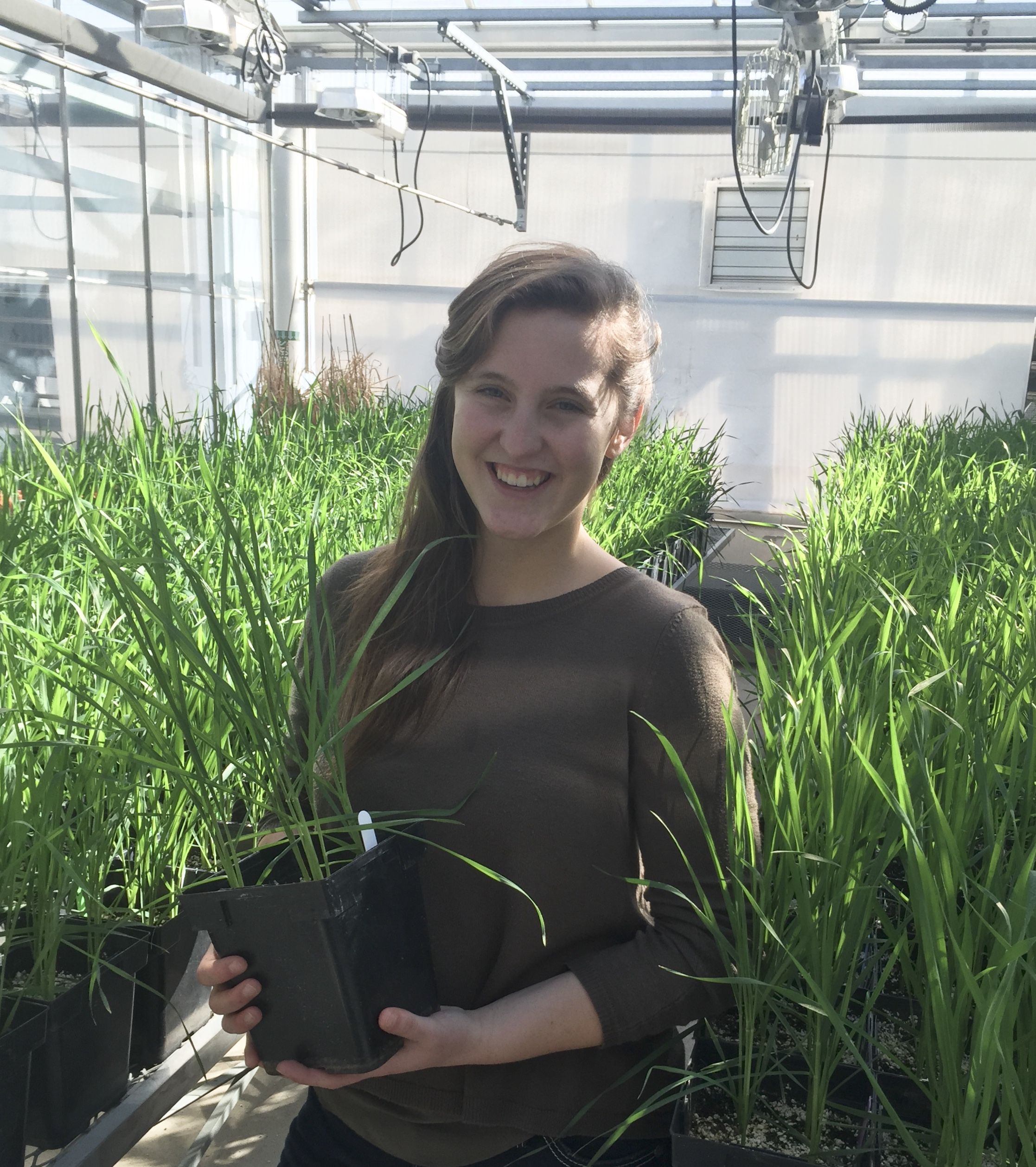

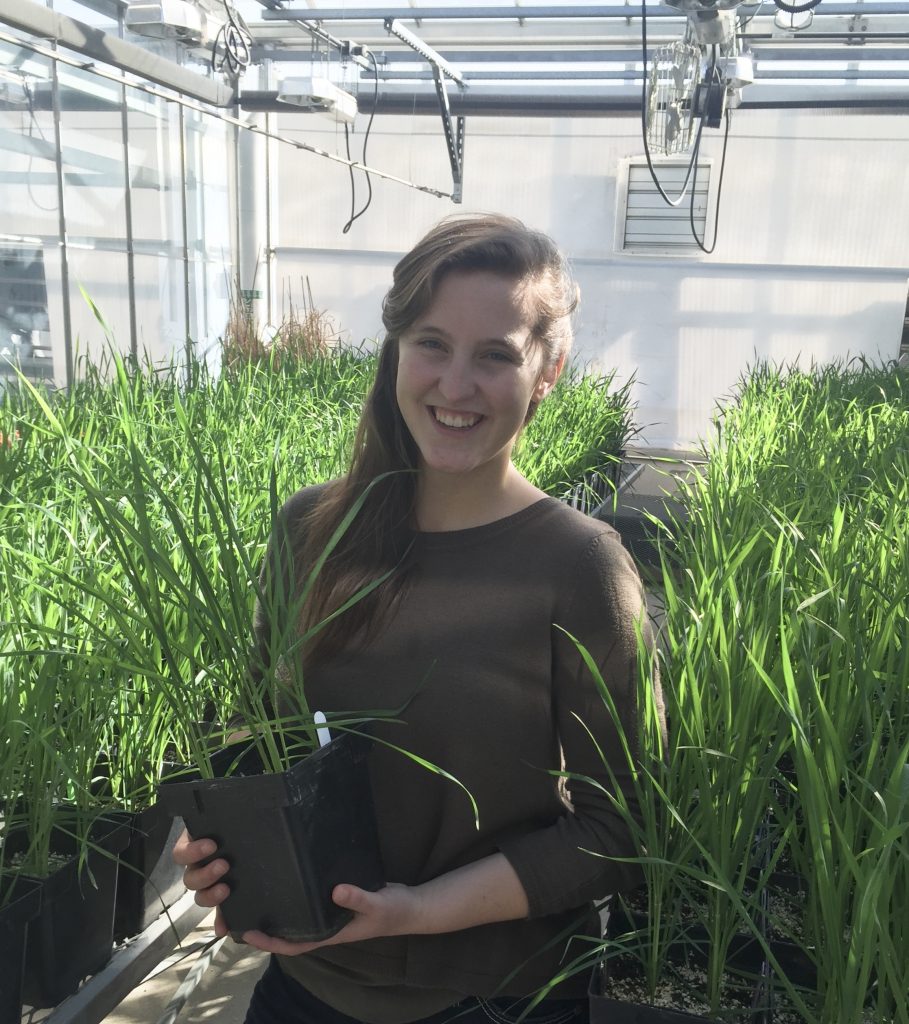

Tessa Mahmoudi

Plant Microbiologist Tessa Mahmoudi, a 2012 World Food Prize’s Borlaug-Ruan summer intern, says her experience working with CIMMYT researchers in Turkey when she was 16 years old profoundly changed her career and her life.

“For a summer I was welcomed to Turkey not as a child, but as a scientist,” says Mahmoudi, who grew up on a farm in southeast Minnesota, USA. “My hosts, Dr. Abdelfattah A. Dababat and Dr. Gül Erginbas-Orakci, who study soil-borne pathogens and the impact those organisms have on food supplies, showed me their challenges and, most importantly, their dedication.”

Mahmoudi explains she still finds the statistics regarding the global food insecurity to be daunting but saw CIMMYT researchers making real progress. “This helped me realize that I had a role to play and an opportunity to make positive impact.”

Among other things, Mahmoudi learned what it meant to be a plant pathologist and the value of that work. “I began to ask scientific questions that mattered,” she says. “And I went back home motivated to study — not just to get good grades, but to solve real problems.”

She says her outlook on the world dramatically broadened. “I realized we all live in unique realities, sheltered by climatic conditions that strongly influence our world views.”

According to Mahmoudi, her internship at CIMMYT empowered her to get out of her comfort zone and get involved in food security issues. She joined the “hunger fighters” at the University of Minnesota while pursuing a bachelor’s in Plant Science. “I was the president of the Project Food Security Club which focuses on bring awareness of global hunger issues and encouraging involvement in solutions.” She also did research on stem rust under Matthew Rouse, winner of the World Food Prize 2018 Norman Borlaug Award for Field Research and Application.

Pursuing a master’s in plant pathology at Texas A&M University under the supervision of Betsy Pierson, she studied the effects of plant-microbe interactions on drought tolerance and, specifically, how plant-microbe symbiosis influences root architecture and wheat’s ability to recover after suffering water stress.

Currently, Mahmoudi is involved in international development and teaching. As a horticulture lecturer at Blinn College in Texas, she engages students in the innovative use of plants to improve food security and global health.

Mahmoudi incorporates interactive learning activities in her class (see her website, https://reachingroots.org/). Her vision is to increase access to plant science education and encourage innovation in agriculture.

“As a teacher and mentor, I am committed to helping students broaden their exposure to real problems because I know how much that influenced me,” Mahmoudi says. “Our world has many challenges, but great teams and projects are making progress, such as the work by CIMMYT teams around the world. We all have a role to play and an idea that we can make a reality to improve global health.”

As an example, Mahmoudi is working with the non-profit Clean Challenge on a project to improve the waste system in Haiti. The initiative links with local teams in Haiti to develop a holistic system for handling trash, including composting organic waste to empower small holder farmers to improve their soil health and food security.

“Without my mentors, I would not have had the opportunity to be involved in these high impact initiatives. Wherever you are in your career make sure you are being mentored and also mentoring. I highly encourage students to find mentors and get involved in today’s greatest challenge, increasing food security.”

In addition to thanking the CIMMYT scientists who inspired her, Mahmoudi is deeply grateful for those who made her summer internship possible. “This would include the World Food Prize Foundation and especially Lisa Fleming, Ambassador Kenneth M. Quinn, the Ruan Family,” she says. “Your commitment to this high-impact, experiential learning opportunity has had lasting impact on my life.”