African leaders rely on science and technology to improve food security

Rural areas in Africa are facing unprecedented challenges. From high levels of rural-urban migration to the need to maintain crop production and food security under the added stress of climate change, rural areas need investment and support. The recent Africa Food Security Leadership Dialogue brought together key regional actors to discuss the current situation as well as ways to catalyze actions and financing to help address Africa’s worsening food security crisis under climate change.

Heads of state, ministers of agriculture and finance, heads of international institutions and regional economic commissions, Nobel laureates, and eminent scientists took part in the dialogue in Kigali, Rwanda, on August 5 and 6, 2019.

This high-level meeting was convened by core partners including the African Union Commission (AUC), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the World Bank.

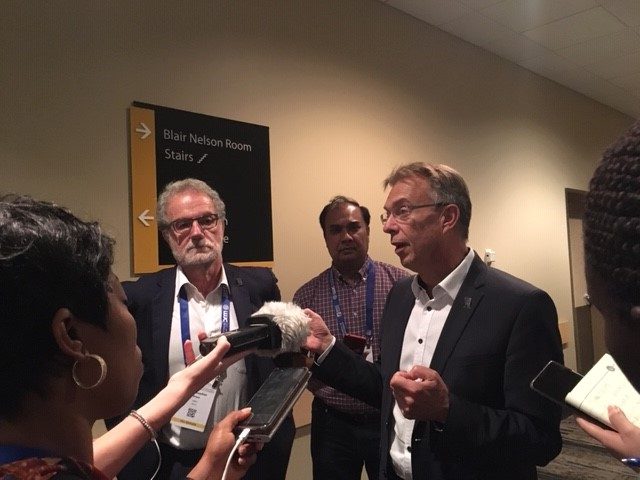

The Director General of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Martin Kropff, participated in a session entitled “Leveraging science to end hunger by 2025”, where he discussed the challenges to adapt Africa’s wheat sector to climate change, and what CIMMYT is doing to help. Demand for wheat is growing faster than any other commodity, and sub-Saharan Africa has tremendous potential to increase wheat production. People in Africa consume nearly 47 million tons of wheat a year. However, more than 80% of that — 39 million tons— is imported and used for human consumption, costing the countries billions of dollars. Kropff discussed the great strides CIMMYT has made in supporting wheat production on the continent despite biological challenges such as Ug99, a dangerous strain of wheat rust native to east Africa.

“The potential for wheat production in Africa is tremendous; existing varieties already realize very high yields but poor agronomic practices often result in low yields,” Kropff said. “The challenges we have to tackle together are as much in reshaping policies in favor of wheat and develop the wheat market and surrounding infrastructure. Africa’s environment is friendly for wheat production, but it needs the right supporting policies to develop a sustainable wheat market.”

Kropff highlighted Ethiopia’s case. “Ethiopia has decided to become self-sufficient in wheat by 2025. CIMMYT is already talking to the government and working with the national system to assure the best varieties and technologies will be used. We are ready to do this with every single African nation that is interested in producing quality wheat.”

Climate change is also posing dire threats to maize, a key staple crop in sub-Saharan Africa.

We talked to Cosmos Magorokosho, CIMMYT researcher and project leader of the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) project, who attended the dialogue, on what CIMMYT can do to better support farmers in Africa’s rural communities.

How can projects such as Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa contribute to protecting food security in Africa in the face of climate change?

Stress-tolerant maize varieties can contribute by cushioning farmers against total crop failures in case of drought and heat stress, among other stresses during the growing season. In addition, stress-tolerant varieties can also yield well under good growing conditions, therefore benefiting farmers both during difficult growing seasons as well as those seasons when conditions are favorable for maize growth.

What can be done to support rural areas and smallholder farmers in Africa to improve food security?

Rural areas and smallholder farmers need support with climate resilient crop varieties, supporting agronomic practices, environment conserving farming practices, labor and drudgery- reducing farm operations, access to affordable finance, and rewarding markets for their produce.

What role can international research organizations such as CIMMYT play in this?

International agricultural research can unlock the potential of small holder farmers through the generation of new appropriate technologies, testing and helping farmers adopt those technologies, refining and fine tuning of new technologies, as well as scaling up and out of farmer-demanded technologies. International agriculture research can influence policy across and within borders, political divide, religion, ecologies, and diversity of farmers.

What would it take for CIMMYT to effectively move science from the lab and package it into solutions that can be disseminated and adopted by majority of small family farms in Africa?

CIMMYT should keep and broaden its engagement with farmers, policy makers, and continue with capacity enhancement of partners to reach scale and bring new cutting-edge smallholder-farmer appropriate technologies to farmers’ fields in the shortest possible timeframe.