“Historic” release of six improved wheat varieties in Nepal

On December 11, 2020, the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) announced the release of six new wheat varieties for multiplication and distribution to the country’s wheat farmers, offering increased production for Nepal’s nearly one million wheat farmers and boosted nutrition for its 28 million wheat consumers.

The varieties, which are derived from materials developed by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), include five bred for elevated levels of the crucial micronutrient zinc, and Borlaug 100, a variety well known for being high yielding, drought- and heat-resilient, and resistant to wheat blast, as well as high in zinc.

“Releasing six varieties in one attempt is historic news for Nepal,” said CIMMYT Asia Regional Representative and Principal Scientist Arun Joshi.

“It is an especially impressive achievement by the NARC breeders and technicians during a time of COVID-related challenges and restrictions,” said NARC Executive Director Deepak Bhandari.

“This was a joint effort by many scientists in our team who played a critical role in generating proper data, and making a strong case for these varieties to the release committee, ” said Roshan Basnet, head of the National Wheat Research Program based in Bhairahawa, Nepal, who was instrumental in releasing three of the varieties, including Borlaug 2020.

“We are very glad that our hard work has paid off for our country’s farmers,” said Dhruba Thapa, chief and wheat breeder at NARC’s National Plant Breeding and Genetics Research Centre.

Nepal produces 1.96 million tons of wheat on more than 750,000 hectares, but its wheat farmers are mainly smallholders with less than 1-hectare holdings and limited access to inputs or mechanization. In addition, most of the popular wheat varieties grown in the country have become susceptible to new strains of wheat rust diseases.

The new varieties — Zinc Gahun 1, Zinc Gahun 2, Bheri-Ganga, Himganga, Khumal-Shakti and Borlaug 2020 — were bred and tested using a “fast-track” approach, with CIMMYT and NARC scientists moving material from trials in CIMMYT’s research station in Mexico to multiple locations in Nepal and other Target Population of Environments (TPEs) for testing.

“Thanks to a big effort from Arun Joshi and our NARC partners we were able to collect important data in first year, reducing the time it takes to release new varieties,” said CIMMYT Head of Wheat Improvement Ravi Singh.

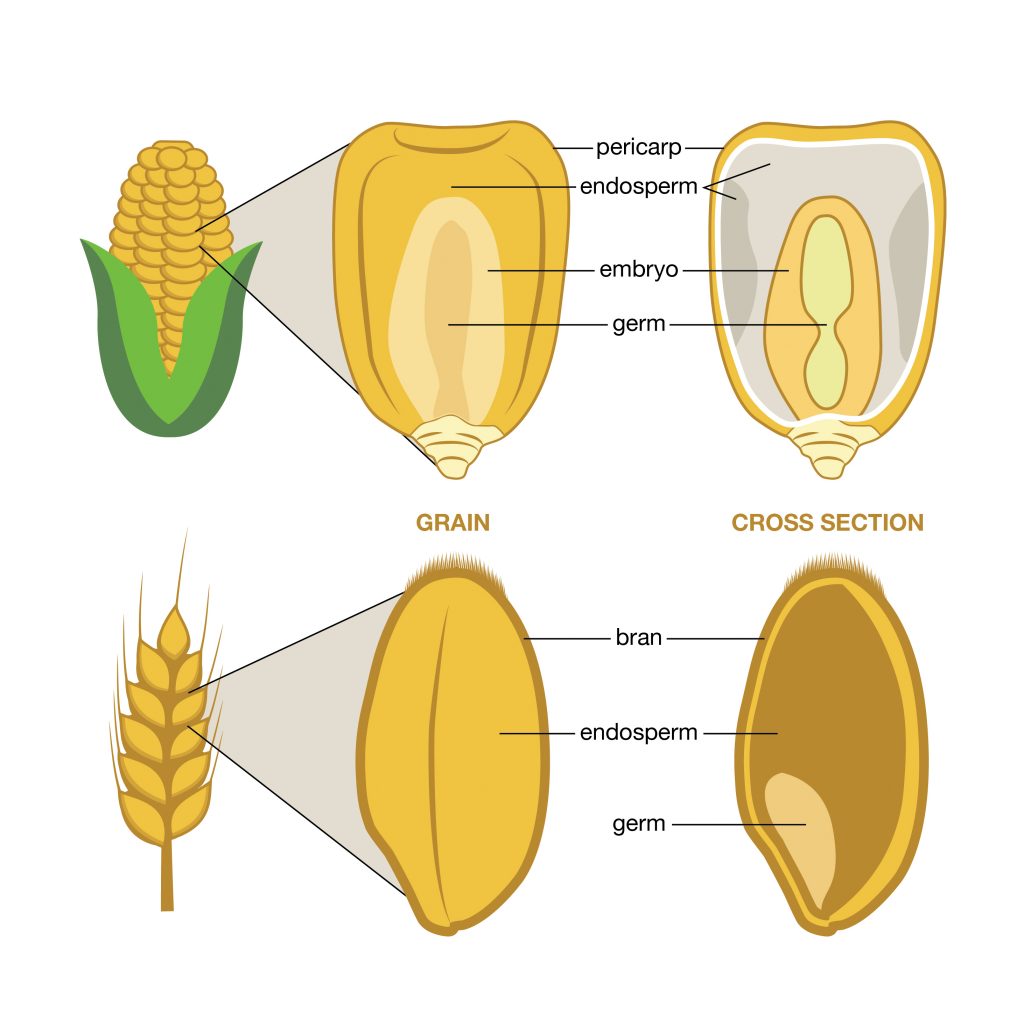

The varieties are tailored for conditions in a range of wheat growing regions in the country — from the hotter lowland, or Terai, regions to the irrigated as well as dryer mid- and high-elevation areas — and for stresses including wheat rust diseases and wheat blast. The five high-zinc, biofortified varieties were developed through conventional crop breeding by crossing modern high yielding wheats with high zinc progenitors such as landraces, spelt wheat and emmer wheat.

“Zinc deficiency is a serious problem in Nepal, with 21% of children found to be zinc deficient in 2016,” explained said CIMMYT Senior Scientist and wheat breeder Velu Govindan, who specializes in breeding biofortified varieties. “Biofortification of staple crops such as wheat is a proven method to help reverse and prevent this deficiency, especially for those without access to a more diverse diet.”

Borlaug 2020 is equivalent to Borlaug 100, a highly prized variety released in 2014 in adbMexico to commemorate the centennial year of Nobel Peace laureate Norman E. Borlaug. Coincidently, its release in Nepal coincides with the 50th anniversary of Borlaug’s Nobel Peace Prize.

NARC staff have already begun the process of seed multiplication and conducting participatory varietal selection trials with farmers, so very soon farmers throughout the country will benefit from these seeds.

“The number of new varieties and record release time is amazing,” said Joshi. “We now have varieties that will help Nepal’s farmers well into the future.”

CIMMYT breeding of biofortified varieties was funded by HarvestPlus. Variety release and seed multiplication activities in Nepal were supported by NARC and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) through collaboration with ADB Natural Resources Principal & Agriculture Specialist Michiko Katagami. This NARC-ADB-CIMMYT collaboration was prompted by World Food Prize winner and former HarvestPlus CEO Howarth Bouis, and provided crucial support that enabled the release in a record time.

RELATED RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS:

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

Arun Joshi, Asia Regional Representative and Principal Scientist, CIMMYT

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT:

Marcia MacNeil, Communications Officer, CIMMYT m.macneil@cgiar.org.

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.

ABOUT NARC:

Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) was established in 1991 as an autonomous organization under Nepal Agricultural Research Council Act – 1991 to conduct agricultural research in the country to uplift the economic level of Nepalese people.

ABOUT ADB:

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty. It assists its members and partners by providing loans, technical assistance, grants, and equity investments to promote social and economic development.