Exploring the potential for blended wheat flours in Kenya

Over the years, wheat-based foods have increasingly been incorporated as part of Kenyan meals. One example is packaged bread, which has become a common feature on Kenyan breakfast tables with millions of loaves from industrial bakeries delivered to retail shops daily, countrywide. Another example is chapati — a round unleavened flat bread. Once reserved for special occasions, chapati can now be purchased from roadside venders throughout the capital Nairobi.

Millers and processors in Kenya are highly dependent on imported wheat to meet the strong demand for wheat-based food products. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine, two of the most important sources of imported wheat for Kenya, presents a major threat to millers and industrial bakeries. Prices for bread and chapati are increasing and may continue to increase. Governments and wheat-related industries are looking at short- and long-term options to reduce utilization of imported wheat. One short-term option is the blending of wheat flour with flour derived from locally available crops, such as cassava, millet or sorghum.

Record-high price of wheat

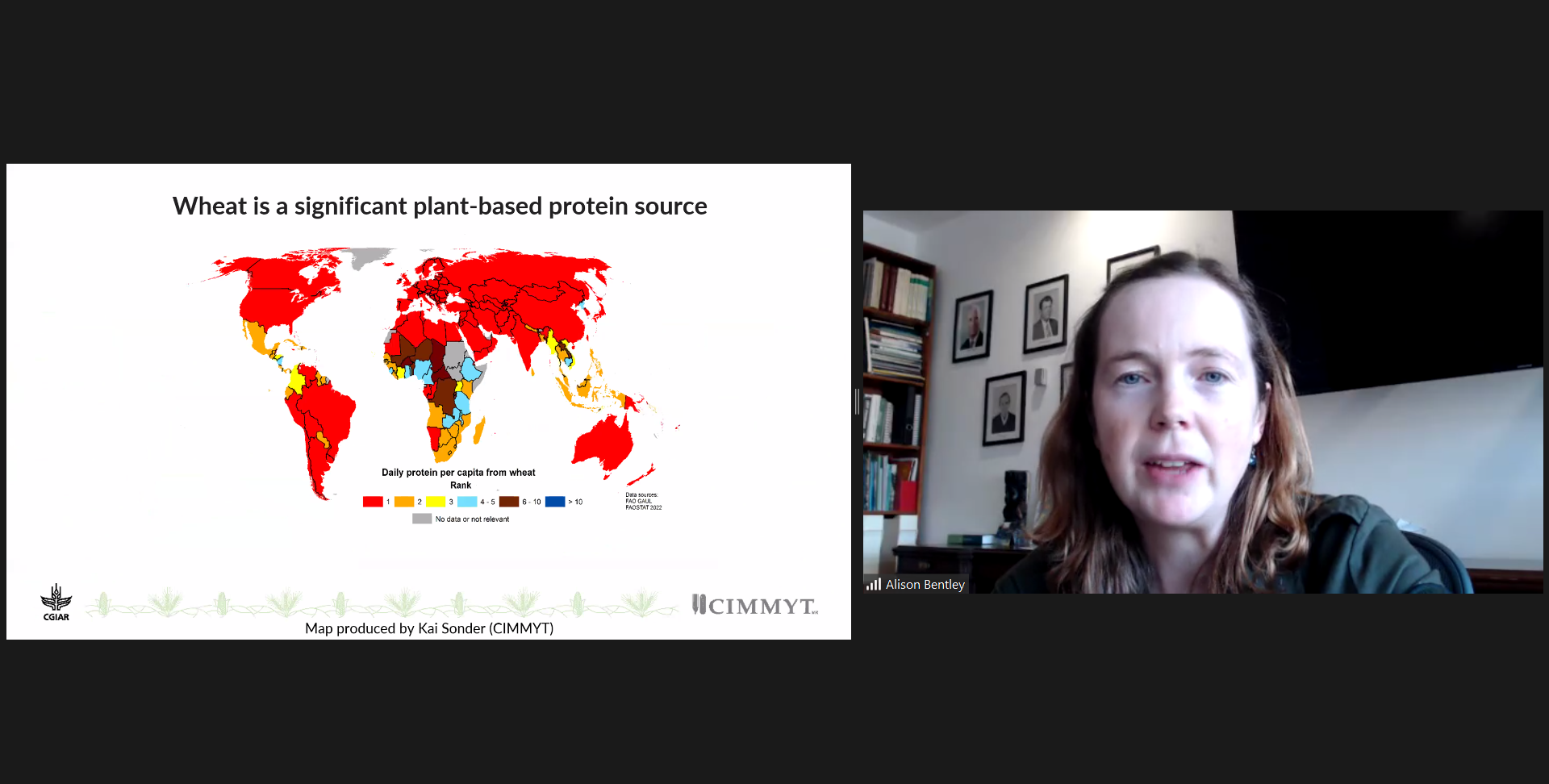

A visit to local industrial bakeries and wheat flour millers on the outskirts of Nairobi by International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) researchers confirmed the effects of record-high global prices of wheat. Global Wheat Program director Alison Bentley and senior economist Jason Donovan had conversations with leaders of industrial bakeries and millers, who gave insights into their grain demands, production processes and sales volumes.

One of the leaders of an established industrial bakery divulged that they use approximately 15,000 tons of wheat flour monthly to make baked products, with only 10% of the wheat obtained locally.

“In the last ten years, local wheat production has comprised about ten to fifteen percent of our cereal mixture for bread, and we were already paying higher prices to farmers compared to import prices. The farmers were already being paid about 30 to 40 dollars more per ton,” a manager of a large baking industry in Kenya explained to the CIMMYT team.

According to government regulations, millers and bakeries must purchase locally produced wheat at agreed prices before they can buy imported wheat. He agreed that though the quality of local wheat is good, the local production cannot compete with the higher volume of imported wheat or its lower price.

Growing wheat in East Africa

It has been more than four months since the Russia-Ukraine conflict unfolded, and since then prices of wheat-based products have been increasing significantly. The current crisis has sparked the debate on low levels of self-sufficiency in food production for many countries. And this is especially the case for wheat in Kenya, and more widely in Africa.

Bentley points out that the biophysical conditions to produce wheat in East Africa are present and favorable. However, more work is needed to strengthen local wheat production, starting with efficient seed systems. Farmers who are interested in growing wheat need access to high performing and stress-tolerant wheat varieties.

Practical response to the crisis

With no certainty as to how long the conflict will continue and climate change resulting in significant crop loss in key production zones, wheat shortages on international markets could become a reality. Blending of wheat flour with locally available crops could be an option as an immediate response to the current scarcity of wheat in East Africa. “Blending [flour] is when for instance five percent of wheat flour is replaced with flour from a different crop such as sorghum or cassava,” Bentley explained.

Donovan added that, though it might seem like a small number, it becomes significant in consideration to the volume of wheat that industries use to make different products, translating into thousands of metric tons. He noted that blending flour therefore has the potential to create a win-win situtation, because it can boost the demand for local crops and address uncertainty and price volatility on international wheat markets.

Consumer acceptance of new products

During a full week of engagements with universities, partners, and industry experts in Kenya, the CIMMYT team explored the current interest of the sector in blending wheat flour. Several partners agreed that this could be a potential way forward for the grain industry but all highlighted one key element: the importance of consumer acceptance. If the functionality of the flour or taste would be negatively influenced by blending wheat flour, it would represent a no-go from the industry, even if blends would have higher nutritional benefits or lower prices. “This reinforces the need to understand consumer preferences and evaluate both the functionality of the flour to produce essential food products such as chapati or bread as well as the taste of those products,” Pieter Rutsaert explained.

CIMMYT researchers Sarah Kariuki and Pieter Rutsaert, both Markets and Value Chain Specialists, and Maria Itria Ibba, Head of the Wheat Quality Lab, are therefore engaging with local millers and universities in Kenya to design bread and chapati products derived from different wheat blends, to include blends comprised of 5%, 15% and 20% of cassava or sorghum. Lab testing and preliminary consumer testing will be used to identify the most promising products. These products will be taken to the streets in urban and peri-urban Nairobi to assess consumer tastes and preferences, through sensory analysis and at-home testing.

The market intelligence gained will offer foundational support for CGIAR’s Seed Equal Initiative to accelerate the growth of a demand-driven seed system. By gathering and analyzing consumer preferences on selected crops for blending, such as from farmers and milling industries, Donovan pointed out that CGIAR breeding will continue to make informed choices and prioritize breeding for specific crops, that seek to address specific challenges, therefore having greater impact.

Donovan noted that data and information from the studies will provide much needed evidence and fill information gaps that will support governments, millers, processors and farmers to make decisions in response to the evolving wheat crisis.