New systems analysis tools help boost the sustainable intensification of agriculture in Bangladesh

DHAKA, Bangladesh (CIMMYT) – In South Asia, the population is growing and land area for agricultural expansion is extremely limited. Increasing the productivity of already farmed land is the best way to attain food security.

In the northwestern Indo-Gangetic Plains, farmers use groundwater to irrigate their fields. This allows them to grow two or three crops on the same piece of land each year, generating a reliable source of food and income for farming families. But in the food-insecure lower Eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains in Bangladesh, farmers have lower investment capacities and are highly risk averse. Combined with environmental difficulties including ground water scarcity and soil and water salinity, cropping is often much less productive.

Could the use of available surface water for irrigation provide part of the solution to these problems? The government of Bangladesh has recently promoted the use of surface water irrigation for crop intensification. The concept is simple: by utilizing the country’s network of largely underutilized natural canals, farmers can theoretically establish at least two well-irrigated and higher-yielding crops per year. The potential for this approach to intensifying agriculture however has various limitations. High soil and water salinity, poor drainage and waterlogging threaten crop productivity. In addition, weakly developed markets, rural to urban out-migration, low tenancy issues and overall production risk limit farmers’ productivity. The systematic nature of these problems calls for new approaches to study how development investments can best be leveraged to overcome these complex challenges to increase cropping intensity.

Policy makers, development practitioners and agricultural scientists recently gathered to respond to these challenges at a workshop in Dhaka. They reviewed research results and discussed potential solutions to common limitations. Representatives from more than ten national research, extension, development and policy institutes participated. The CSISA-supported workshop however differed from conventional approaches to research for development in agriculture, in that it explicitly focused on interdisciplinary and systems analysis approaches to addressing these complex problems.

Systems analysis is the process of studying the individual parts and their integration into complex systems to identify ways in which more effective and efficient outcomes can be attained. This workshop focused on these approaches and highlighted new advances in mathematical modeling, geospatial systems analysis, and the use of systems approaches to farmer behavioral science.

Timothy J. Krupnik, Systems Agronomist at CIMMYT and CSISA Bangladesh country coordinator, gave an overview of a geospatial assessment of landscape-scale irrigated production potential in coastal Bangladesh to start the talks.

For the first time in Bangladesh, research using cognitive mapping, a technique developed in cognitive and behavioral science that can be used to model farmers’ perceptions of their farming systems, and opportunities for development interventions to overcome constraints to intensified cropping, was described. This work was conducted by Jacqueline Halbrendt and presented by Lenora Ditzler, both with the Wageningen University.

“This research and policy dialogue workshop brought new ideas of farming systems and research, and has shown new and valuable tools to analyze complex problems and give insights into how to prioritize development options,” said Executive Director of the Krishi Gobeshona Foundation, Wais Kabir.

Workshop participants also discussed how to prioritize future development interventions, including how to apply a new online tool that can be used to target irrigation scheme planning, which arose from the work presented by Krupnik. Based on the results of these integrated agronomic and socioeconomic systems analyses, participants also learned how canal dredging, drainage, micro-finance, extension and market development must be integrated to achieve increases in cropping intensity in southern Bangladesh.

Mohammad Saidur Rahman, Assistant Professor, Seed Science and Technology department at Bangladesh Agriculture University, also said he appreciated the meeting’s focus on new methods. He indicated that systems analysis can be applied not only to questions on cropping intensification in Bangladesh, but to other crucial problems in agricultural development across South Asia.

The workshop was organized by the Enhancing the Effectiveness of Systems Analysis Tools to Support Learning and Innovation in Multi-stakeholder Platforms (ESAP) project, an initiative funded by the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE) through the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and supported in Bangladesh through the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA). ESAP is implemented by Wageningen University’s Farming Systems Ecology group and the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT).

CSISA is a CIMMYT-led initiative implemented jointly with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). CSISA works to increase the adoption of various resource-conserving and climate-resilient technologies by operating in rural “innovation hubs” in Bangladesh, India and Nepal, and seeks to improve farmers’ access to market information and enterprise development.

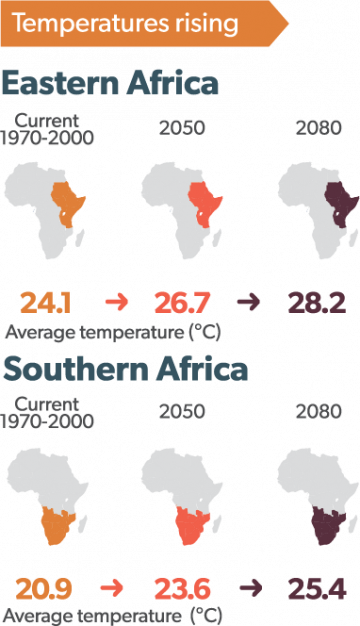

Food security is at the heart of Africa’s development agenda. However, climate change is threatening

Food security is at the heart of Africa’s development agenda. However, climate change is threatening

One of the 10 stories in the book shows how the

One of the 10 stories in the book shows how the

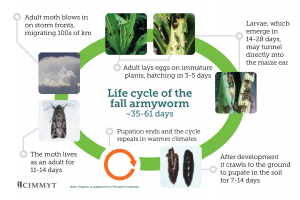

DES MOINES, Iowa (CIMMYT) – Without proper control methods, the Fall Armyworm (FAW) menace could lead to maize yield losses estimated at $2.5 to $6.2 billion a year in just 12 of the 28 African countries where the pest has been confirmed, scientists from the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, (CABI)

DES MOINES, Iowa (CIMMYT) – Without proper control methods, the Fall Armyworm (FAW) menace could lead to maize yield losses estimated at $2.5 to $6.2 billion a year in just 12 of the 28 African countries where the pest has been confirmed, scientists from the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, (CABI)  Prasanna will be participating in the 2017 Borlaug Dialogue in Des Moines, Iowa, and will part of a panel discussion, on October 19, titled “

Prasanna will be participating in the 2017 Borlaug Dialogue in Des Moines, Iowa, and will part of a panel discussion, on October 19, titled “