The cereals imperative of future food systems

Pioneering research on our three most important cereal grains — maize, rice, and wheat — has contributed enormously to global food security over the last half century, chiefly by boosting the yields of these crops and by making them more resilient in the face of drought, flood, pests and diseases. But with more than 800 million people still living in chronic hunger and many more suffering from inadequate diets, much remains to be done. The challenges are complicated by climate change, rampant degradation of the ecosystems that sustain food production, rapid population growth and unequal access to resources that are vital for improved livelihoods.

In recent years, a consensus has emerged among agricultural researchers and development experts around the need to transform global food systems, so they can provide healthy diets while drastically reducing negative environmental impacts. Certainly, this is a central aim of CGIAR — the world’s largest global agricultural research network — which views enhanced nutrition and sustainability as essential for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. CGIAR scientists and their many partners contribute by developing technological and social innovations for the world’s key crop production systems, with a sharp focus on reducing hunger and poverty in low- and middle-income countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The importance of transforming food systems is also the message of the influential EAT-Lancet Commission report, launched in early 2019. Based on the views of 37 leading experts from diverse research disciplines, the report defines specific actions to achieve a “planetary health diet,” which enhances human nutrition and keeps the resource use of food systems within planetary boundaries. While including all food groups — grains, roots and tubers, pulses, vegetables, fruits, tree nuts, meat, fish, and dairy products — this diet reflects important shifts in their consumption. The major cereals, for example, would supply about one-third of the required calories but with increased emphasis on whole grains to curb the negative health effects of cheap and abundant supplies of refined cereals.

This proportion of calories corresponds roughly to the proportion of its funding that CGIAR currently invests in the major cereals. These crops are already vital in diets, cultures, and economies across the developing world, and the way they are produced, processed and consumed must be a central focus of global efforts to transform food systems. There are four main reasons for this imperative.

1. Scale and economic importance

The sheer extent of major cereal production and its enormous value, especially for the poor, account in large part for the critical importance of these crops in global food systems. According to 2017 figures, maize is grown on 197 million hectares and rice on more than 167 million hectares, mainly in Asia and Africa. Wheat covers 218 million hectares, an area larger than France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK combined. The total annual harvest of these crops amounts to about 2.5 billion tons of grain.

Worldwide production had an estimated annual value averaging more than $500 billion in 2014-2016. The prices of the major cereals are especially important for poor consumers. In recent years, the rising cost of bread in North Africa and tortillas in Mexico, as well as the rice price crisis in Southeast Asia, imposed great hardship on urban populations in particular, triggering major demonstrations and social unrest. To avoid such troubles by reducing dependence on cereal imports, many countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have made staple crop self-sufficiency a central element of national agriculture policy.

2. Critical role in human diets

Cereals have a significant role to play in food system transformation because of their vital importance in human diets. In developing countries, maize, rice, and wheat together provide 48% of the total calories and 42% of the total protein. In every developing region except Latin America, cereals provide people with more protein than meat, fish, milk and eggs combined, making them an important protein source for over half the world’s population.

Yellow maize, a key source of livestock feed, also contributes indirectly to more protein-rich diets, as does animal fodder derived from cereal crop residues. As consumption of meat, fish and dairy products continues to expand in the developing world, demand for cereals for food and feed must rise, increasing the pressure to optimize cereal production.

In addition to supplying starch and protein, the cereals serve as a rich source of dietary fiber and nutrients. CGIAR research has documented the important contribution of wheat to healthy diets, linking the crop to reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colorectal cancer. The nutritional value of brown rice compared to white rice is also well known. Moreover, the recent discovery of certain genetic traits in milled rice has created the opportunity to breed varieties that show a low glycemic index without compromising grain quality.

3. Encouraging progress toward better nutritional quality

The major cereals have undergone further improvement in nutritional quality during recent years through a crop breeding approach called “biofortification,” which boosts the content of essential vitamins or micronutrients. Dietary deficiencies of this kind harm children’s physical and cognitive development, and leave them more vulnerable to disease. Sometimes called “hidden hunger,” this condition is believed to cause about one-third of the 3.1 million annual child deaths attributed to malnutrition. Diverse diets are the preferred remedy, but the world’s poorest consumers often cannot afford more nutritious foods. The problem is especially acute for women and adolescent girls, who have unequal access to food, healthcare and resources.

It will take many years of focused effort before diverse diets become a reality in the lives of the people who need them most. Diversified farming systems such as rice-fish rotations that improve nutritional value, livelihoods and resilience are a step in that direction. In the meantime, “biofortified” cereal and other crop varieties developed by CGIAR help address hidden hunger by providing higher levels of zinc, iron and provitamin A carotenoids as well as better protein quality. Farmers in many developing countries are already growing these varieties.

A 2018 study in India found that young children who ate zinc-biofortified wheat in flatbread or porridge became ill less frequently. Other studies have shown that consumption of provitamin A maize improves the body’s total stores of this vitamin as effectively as vitamin supplementation. Biofortified crop varieties are not a substitute for food fortification (adding micronutrients and vitamins during industrial food processing). But these varieties can offer an immediate solution to hidden hunger for the many subsistence farmers and other rural consumers who depend on locally produced foods and lack access to fortified products.

4. Wide scope for more sustainable production

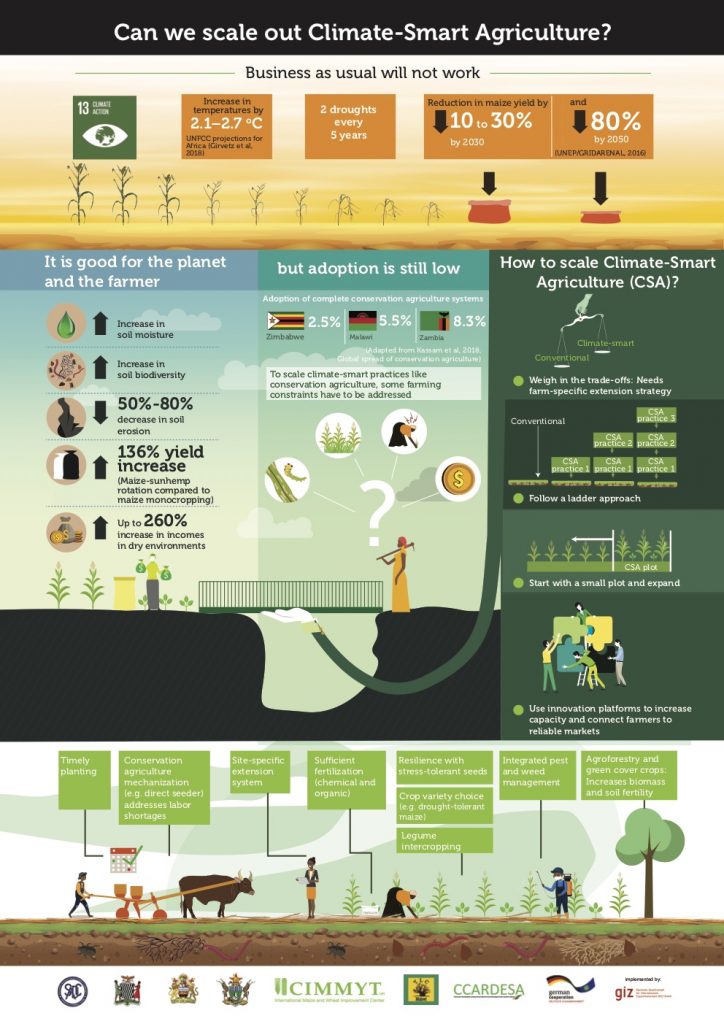

Cereal crops show much potential not only for enhancing human heath but that of the environment as well. Compared to other crops, the production of cereals has relatively low environmental impact, as noted in the EAT-Lancet report. Still, it is both necessary and feasible to further enhance the sustainability of cereal cropping systems. Many new practices have a proven ability to conserve water as well as soil and land, and to use purchased inputs (pesticides and fertilizers) far more efficiently. With innovations already available, the amount of water used in current rice cultivation techniques, for example, can be significantly reduced from its present high level.

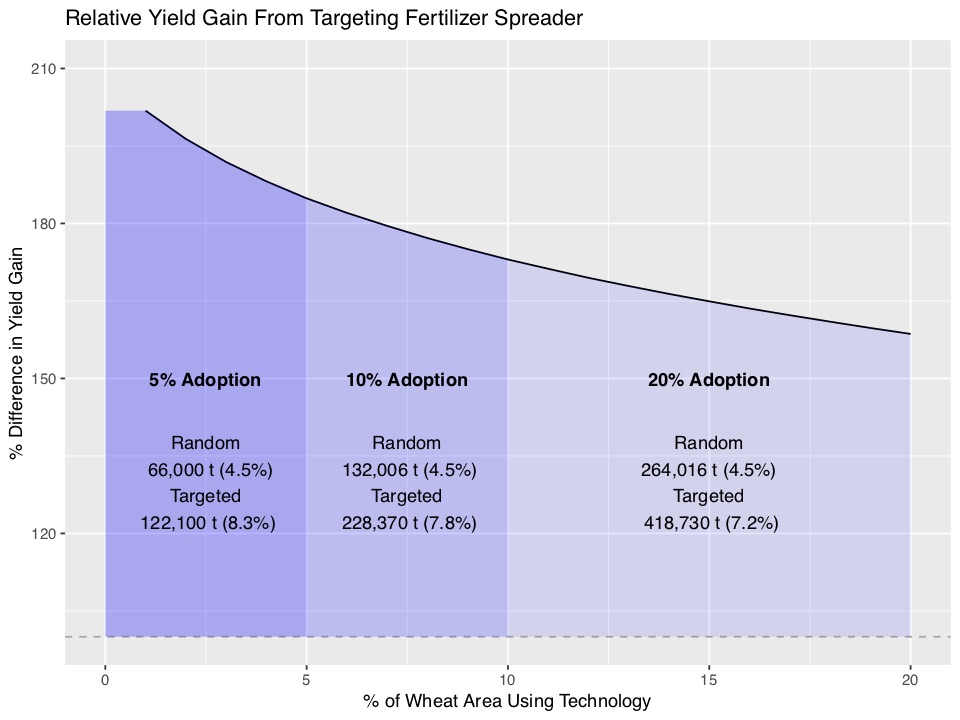

Irrigation scheduling, laser land leveling, drip irrigation, conservation tillage, precision nitrogen fertilization, and cereal varieties tolerant to drought, flooding and heat are among the most promising options. In northwest India, scientists recently determined that optimal practices can reduce water use by 40%, while maintaining yields in rice-wheat rotations. There and in many other places, the adoption of new practices to improve cereal production in the wet season not only leads to more efficient resource use but also creates opportunities to diversify crop production in the dry season. Improvements to increase cereal crop yields also reduces their environmental footprint; using less land, enhancing carbon sequestration and biodiversity and, for rice, reducing methane emissions per kilo of rice produced. Given the enormous extent of cereals cultivation, any improvement in resource use efficiency will have major impact, while also freeing up vast amounts of land for other crops or natural vegetation.

A major challenge now is to improve access to the knowledge and inputs that will enable millions of farmers to adopt new techniques, making it possible both to diversify production and grow more with less. Another key requirement consists of clear signals from policymakers, especially where land and water are limited, about the priority use of these resources — for example, irrigating low-value cereals to bolster food security versus applying the water to higher value crops and importing staple cereals.

Toward a sustainable dietary revolution

Future-proofing the global food system requires bold steps. Policy and research need to support a double transformation, centered on nutrition and sustainability.

CGIAR works toward nutritional transformation of our food system through numerous global partnerships. We give high priority to improving cereal crop systems and food products, because of their crucial importance for a growing world population. Recognizing that this alone will not suffice for healthy diets, we also strongly promote greater dietary diversity through our research on various staple crops and production systems and by raising public awareness of more balanced and nutritious diets.

To help achieve a sustainability transformation, CGIAR researchers and partners have developed a wide array of techniques that use resources more efficiently, enhance the resilience of food production in the face of climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while achieving sustainable increases in crop yields. At the same time, we are generating new evidence on which techniques work best under what conditions to target the implementation of these solutions more effectively.

The ultimate impact of our work depends crucially on the growing resolve of developing countries to promote better diets and more sustainable food production through strong policies and programs. CGIAR is well prepared to help strengthen these measures through research for development, and we are confident that our work on cereals, with continued donor support, will have high relevance, generating a wealth of innovations that help drive the transformation of global food systems.

Martin Kropff is the Director General of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Matthew Morell is the Director General of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

On the transformations that need to happen

On the transformations that need to happen