Agriculture is always impacted by war. However, Russia’s war in Ukraine, fought between two major agricultural producers in an era of globalized markets, poses unprecedented implications for global agriculture and food security. Russia and Ukraine are significant exporters of maize, wheat, fertilizers, edible oils and crude oil. These exports have been compromised by the war, with the greatest impact being on poor and low-income countries that rely most on food imports. Partly because of the Ukraine-Russia conflict and partly due to the decline in agricultural production caused by the climate emergency, food prices have increased between 9.5 and 10.5 percent over the past ten years.

Nepal, where one in four families is impoverished, is an example of a low-income country impacted by the war’s disruption of trade in agricultural goods and inputs. Although wheat, maize and rice are staples, vegetables are also important for nutrition and income, and Nepal imports fuel and fertilizer for their domestic production. Uncertainty in global supply chains, combined with the Nepali rupee’s significant depreciation against the US dollar, has resulted in a 500% increase in the cost of diesel since 2012.

Irrigation to boost homegrown production

Land irrigation is crucial to crop growth and to the capacity of famers to withstand the effects of the climate emergency and economic shock. However, the majority of Nepal’s groundwater resources are underutilized, leaving ample room for increasing climate-resilient agricultural production capable of withstanding an increasing number of drought events. With the right kind of management of its groundwater, Nepal can increase its domestic output, and bolster smallholder resilience and food security in times of economic and climate crisis.

As part of the first prong of this approach, the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) advises farmers (particularly women), governments and donors on the targeted support available to enable them to access existing low-cost and fuel-efficient engineering solutions. These solutions can contribute to the immediate goals of increasing agricultural productivity, intensifying groundwater irrigation and improving rural livelihoods. CSISA informs small producers about ways to access irrigation and develop water entrepreneurship. It also and empowers farmers, especially women, to improve service provision and gain access to services and irrigation pumps, including through access to finance.

Policymakers, businesses, researchers and farmers (especially women, youth and marginalized groups) will collaborate to co-create business models for sustainable and inclusive irrigation with development partners and Nepali public and private sector actors. While there are more than one million wells and pumps in Nepal, many of these are not used efficiently, and social barriers often preclude farmers from accessing services such as pump rentals when they need them. To address these constraints and support private investment in irrigation and water entrepreneurship models, CSISA will work with existing infrastructure investment programs and local stakeholders to build a dynamic and more inclusive irrigation sector over the course of the next year, positively impacting a projected 20,000 small farming households.

At the macro-level, these water entrepreneurship models will respond to prioritized irrigation scaling opportunities, while at the farm level they will respond to irrigation application scheduling advisories. CSISA will also create policy brief documents, in the form of an improved farm management advisory, to be distributed widely among partners and disseminated among farmers to support increases in production and resilience. CSISA’s sustainable and inclusive irrigation framework guides its crisis response.

Scaling digital groundwater monitoring to support adaptive water management

In growing resilience-building irrigation investments, there is always a risk of groundwater depletion, which means that accurate and efficient groundwater data collection is vital. However, Nepal doesn’t currently have a data or governance system for monitoring the impact of irrigation on groundwater resources.

To tackle the need for low-cost, context-specific data systems which improve groundwater data collection, as well as mechanisms for the translation of data into actionable information, and in response to farmer, cooperative and government agency stakeholder demands, the Government of Nepal Groundwater Resources Development Board (GWRDB) and CSISA have co-developed and piloted a digital groundwater monitoring system for Nepal.

In a recent ministerial level workshop, GWRDB executive director Bishnu Belbase said, “CSISA support for groundwater monitoring as well as the ongoing support for boosting sustainable and inclusive investments in groundwater irrigation are cornerstone to the country’s development efforts.”

A pilot study conducted jointly by the two organizations in 2021 identified several options for upgrading groundwater monitoring systems. Three approaches were piloted, and a phone-based monitoring system with a dashboard was evaluated and endorsed as the best fit for Nepal. To ensure the sustainability of the national response to the production crisis, the project will extend government monitoring to cover at least five Tarai districts within the Feed the Future Zone of Influence, collecting data on a total of 100 wells and conducting an assessment of potential network expansion in Nepal’s broad, inner-Tarai valleys and Mid-Hills regions. The goal is to utilize this data to strengthen the Feed the Future Zone of Influence in Nepal by increasing GWRDB’s capability to monitor groundwater in five districts.

Ensuring food security

These activities will be continued for next two years. During that time CSISA will increase GWRDB’s capacity to monitor groundwater and apply this to five districts in Nepal’s Feed the Future Zone of Influence, using an enhanced monitoring system which will assist planners and decision-makers in developing groundwater management plans. As a result, CSISA expects to support at least 20,000 farming households in gaining better irrigation access to achieve high yields and climate-resilient production, with 40 percent of them being women, youth and/or marginalized groups. This access will be made possible through the involvement of the private sector, as CSISA will develop at least two promising business models for sustainable and inclusive irrigation. Finally, through this activity government and private sector stakeholders in Western Nepal will have increased their capacity for inclusive irrigation and agricultural value chain development.

CSISA’s Ukraine Response Activities towards boosting sustainable and inclusive irrigation not only respond to crucial issues and challenges in Nepal, but will also contribute to the regional knowledge base for irrigation investments. Many regions in South Asia face similar challenges and the experience gained from this investment in Nepal will be applicable across the region. Given the importance of of groundwater resources for new farming systems and food system transformation, the project is mapped to Transforming Agrifood Systems in South Asia (TAFSSA), the One CGIAR regional integrated initiative for South Asia, that will act as a scaling platform for sharing lessons learned and coordinating with stakeholder regionally towards more sustainable groundwater management and irrigation investments.

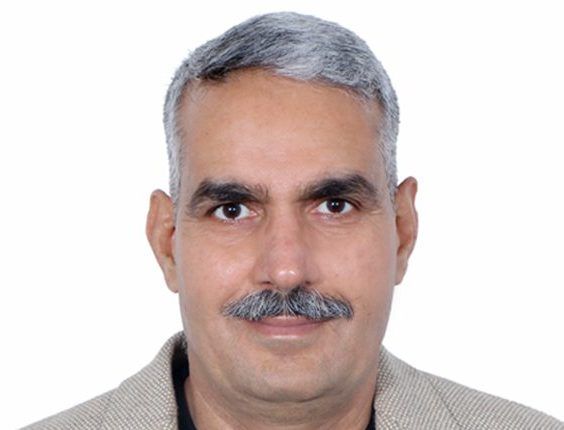

Cover photo: Ram Bahadur Thapa managing water in his paddy field in Dailekh district of Nepal. (Photo: Nabin Baral)