CIMMYT calls for direct agricultural investment to address Sudan’s food crisis

Nairobi, Kenya — 26 June 2024 — CIMMYT calls upon the global community to take immediate and decisive action to address the worsening food crisis in Sudan. As the country teeters on the brink of a famine that could surpass the devastating Ethiopian famine of the 1980s, CIMMYT emphasizes the critical need for both emergency food aid and long-term investment in Sudanese agriculture.

Nairobi, Kenya — 26 June 2024 — CIMMYT calls upon the global community to take immediate and decisive action to address the worsening food crisis in Sudan. As the country teeters on the brink of a famine that could surpass the devastating Ethiopian famine of the 1980s, CIMMYT emphasizes the critical need for both emergency food aid and long-term investment in Sudanese agriculture.

Urgent humanitarian needs and long-term solutions

Recent reports indicate that the ongoing civil war in Sudan has created the world’s most severe humanitarian crisis, with millions of people facing acute food shortages due to the impact of climate change, blocked aid deliveries, failing agricultural systems and infrastructure, and continued conflict. In response, CIMMYT highlights the necessity of balancing emergency aid with sustainable agricultural development to prevent recurring food crises.

“The escalating food crisis in Sudan demands not only immediate emergency assistance but also strategic investment in the country’s agricultural sector to ensure food security and stability,” said Director General of CIMMYT, Bram Govaerts. “We must break away from the aid-dependency model and support Sudanese farmers directly, empowering them to rebuild their livelihoods and contribute to the nation’s recovery as well as todays food availability.”

CIMMYT’s commitment to Sudanese agriculture

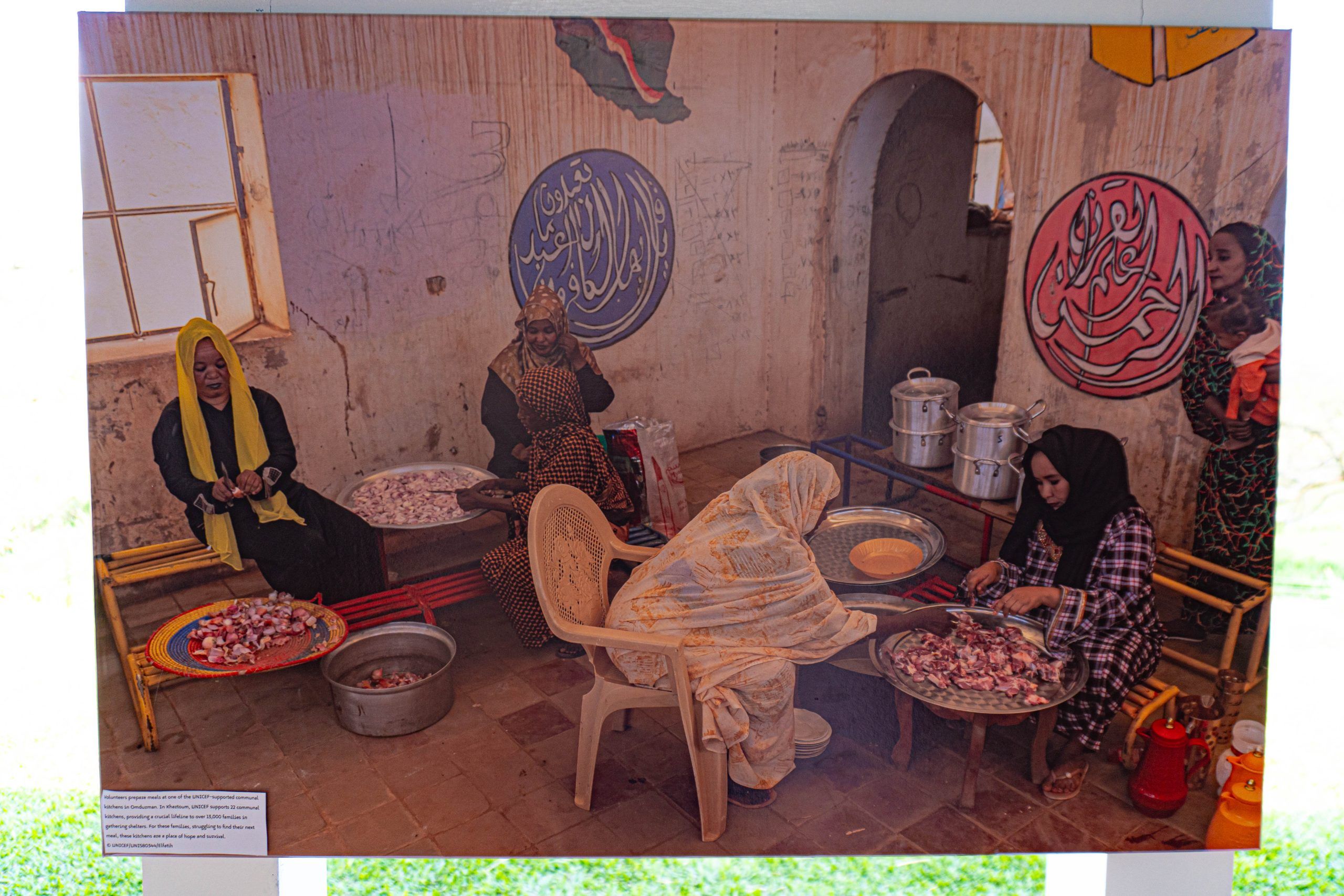

CIMMYT, alongside other international organizations and NGOs, has been actively working in Sudan to support farmers and improve agricultural productivity as part of the Sustainable Agrifoods Systems Approach to Sudan (SASAS) project in collaboration with USAID. With the outbreak of the civil war, SASAS has pivoted to be acutely focused on interventions that support and underpin food security in Sudan, with 13 partners operating across 7 States as the largest operating consortium on-the-ground in the country. Activities range from the provision of improved seeds and agricultural technologies to vaccination campaigns and community resource (water, land) management.

Investing in agricultural resilience

CIMMYT’s initiatives have shown significant impact, even amidst conflict. For example, the Al Etihad women-led farmer cooperative in South Kordofan has empowered its members to improve their production and incomes through collective resource management, training on best practice farming techniques, provision of agricultural inputs, and structured business planning. This cooperative model is essential for building resilience and ensuring food security in Sudanese communities.

“Sudan’s need for food assistance is growing exponentially, but donors have provided only 3.5 percent of requested aid. This gets the story backwards. Food insecurity is at the root of many conflicts. Peace remains elusive without well-functioning agricultural systems, and it is unreasonable to expect viable agricultural production without peace,” Govaerts stated.

Call for global action

CIMMYT urges the international community to –

- Increase funding: Support the UN humanitarian appeal for Sudan, which has received only 16% of the necessary funds.

- Facilitate aid deliveries: Press all parties in the conflict to allow unobstructed humanitarian access, particularly through critical routes such as the Adré crossing from Chad.

- Invest in agriculture: Commit to immediate agricultural development by supporting Sudanese farmers with training, resources, and infrastructure improvements so they can produce locally the needed food.

- Do not forget: It is easy to overlook the war in Sudan with more publicized conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. Leaders must continue to highlight the challenges Sudan faces and the global reverberation of their precarious food security situation.

A path forward

The confluence of conflict, climate change, and economic instability has overwhelmed Sudan. However, by investing directly in the country’s agricultural sector, the international community can help break the cycle of crisis, fostering economic activity and political stability. Let us not forget, no food without peace and you cannot build peace on empty stomachs, so no peace without food.

About CIMMYT

CIMMYT is a cutting-edge, non-profit, international organization dedicated to solving tomorrow’s problems today. It is entrusted with fostering improved quantity, quality, and dependability of production systems and basic cereals such as maize, wheat, triticale, sorghum, millets, and associated crops through applied agricultural science, particularly in the Global South, through building strong partnerships. This combination enhances the livelihood trajectories and resilience of millions of resource-poor farmers while working towards a more productive, inclusive, and resilient agrifood system within planetary boundaries.

Media Contact: Jelle Boone

Head of Communications, CIMMYT

Email: j.boone@cgiar.org

Mobile: +52 595 124 7241

For more information about CIMMYT’s work in Sudan and other initiatives, please visit staging.cimmyt.org.