Seed systems in Nepal are going digital

In Nepal, it takes at least a year to collate the demand and supply of a required type and quantity of seed. A new digital seed information system is likely to change that, as it will enable all value chain actors to access information on seed demand and supply in real time. The information system is currently under development, as part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

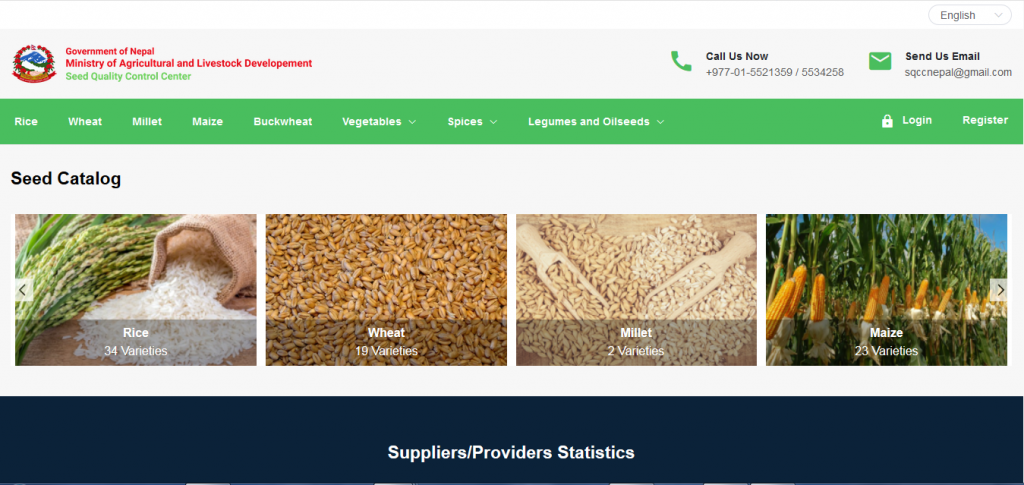

In this system, a national database allows easy access to an online seed catalogue where characteristics and sources of all registered varieties are available. A balance sheet simultaneously gathers and shares real time information on seed demand and supply by all the stakeholders. The digital platform also helps to plan and monitor seed production and distribution over a period of time.

Challenges to seed access

Over 2,500 seed entrepreneurs engaged in production, processing and marketing of seeds in Nepal rely on public research centers to get early generation seeds of various crops, especially cereals, for subsequent seed multiplication.

“The existing seed information system is cumbersome and the process of collecting information takes a minimum of one year before a seed company knows where to get the required amount and type of seed for multiplication,” said Laxmi Kant Dhakal, Chairperson of the Seed Entrepreneurs Association of Nepal (SEAN) and owner of a seed company in the far west of the country. Similarly, more than 700 rural municipalities and local units in Nepal require seeds to multiply under farmers cooperatives in their area.

One of the critical challenges farmers encounter around the world is timely access to quality seeds, due to unavailability of improved varieties, lack of information about them, and weak planning and supply management. Asmita Shrestha, a farmer in Surkhet district, has been involved in maize farming for the last 20 years. She is unaware of the availability of different types of maize that can be productive in the mid-hill region and therefore loses the opportunity to sow improved maize seeds and produce better harvests.

In Sindhupalchowk district, seed producer Ambika Thapa works in a cooperative and produces hybrid tomato seeds. Her problem is getting access to the right market that can provide a good profit for her efforts. A kilogram of hybrid tomato seed can fetch up to $2,000 in a retail and upscale market. However, she is not getting a quarter of this price due to lack of market information and linkages with buyers. This is the story of many Nepali female farmers, who account for over 60% of the rural farming community, where lack of improved technologies and access to profitable markets challenge farm productivity.

At present, the Seed Quality Control Center (SQCC), Nepal Agriculture Research Council (NARC), the Centre for Crop Development and Agro Bio-diversity Conservation (CCDABC) and the Vegetable Development Directorate (VDD) are using paper-based data collection systems to record and plan seed production every year. Aggregating seed demand and supply data and generating reports takes at least two to three months. Furthermore, individual provinces need to convene meetings to collect and estimate province-level seed demand that must come from rural municipalities and local bodies.

A digital technology solution

CIMMYT and its partners are leveraging digital technologies to create an integrated Digitally Enabled Seed Information System (DESIS) that is efficient, dynamic and scalable. This initiative was the result of collaboration between U.S. Global Development Lab and USAID under the Digital Development for Feed the Future (D2FTF) initiative, which aimed to demonstrate that digital tools and approaches can accelerate progress towards food security and nutrition goals.

FHI 360 talked to relevant stakeholders in Nepal to assess their needs, as part of the Mobile Solutions Technical Assistance and Research (mSTAR) project, funded by USAID. Based on this work, CIMMYT and its partners identified a local IT expert and launched the development of DESIS.

DESIS will provide an automated version of the seed balance sheet. Using unique logins, agencies will be able to place their requests and seed producers to post their seed supplies. The platform will help to aggregate and manage breeder, foundation and source seed, as well as certified and labelled seed. The system will also include an offline seed catalogue where users can view seed characteristics, compare seeds and select released and registered varieties available in Nepal. Users can also generate seed quality reports on batches of seeds.

“As the main host of this system, the platform is well designed and perfectly applicable to the needs of SQCC,” said Madan Thapa, Chief of SQCC, during the initial user tests held at his office. Thapa also expressed the potential of the platform to adapt to future needs.

The system will also link farmers to seed suppliers and buyers, to build a better internal Nepalese seed market. The larger goal of DESIS is to help farmers grow better yields and improve livelihoods, while contributing to food security nationwide.

DESIS is planned to roll out in Nepal in early 2020. Primary users will be seed companies, agricultural research centers, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, agrovets, cooperatives, farmers, development partners, universities, researchers, policy makers, and international institutions. The system is based on an open source software and will be available on a mobile website and Android app.

“It is highly secure, user friendly and easy to update,” said Warren Dally, an IT consultant who currently oversees the technical details of the software and the implementation process.

As part of the NSAF project, CIMMYT is also working to roll out digital seed inspection and a QR code-based quality certification system. The higher vision of the system is to create a seed data warehouse that integrates the seed information portal and the seed market information system.

Digital solutions are critical to link the agricultural market with vital information so farmers can make decisions for better production and harvest. It will not be long before farmers like Asmita and Ambika can easily access information using their mobile phones on the type of variety suitable to grow in their region and the best market to sell their products.