Enhancing the resilience of our farmers and our food systems: global collaboration at DialogueNEXT

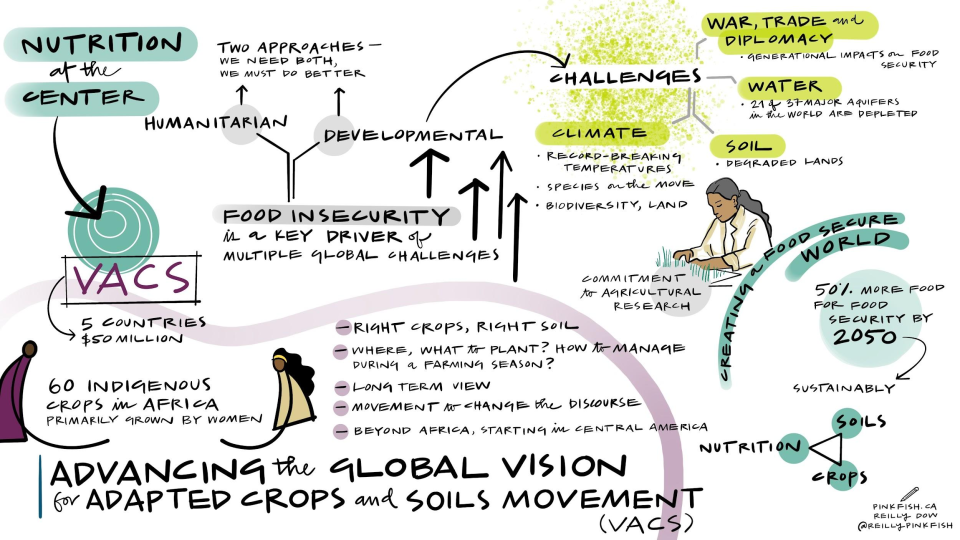

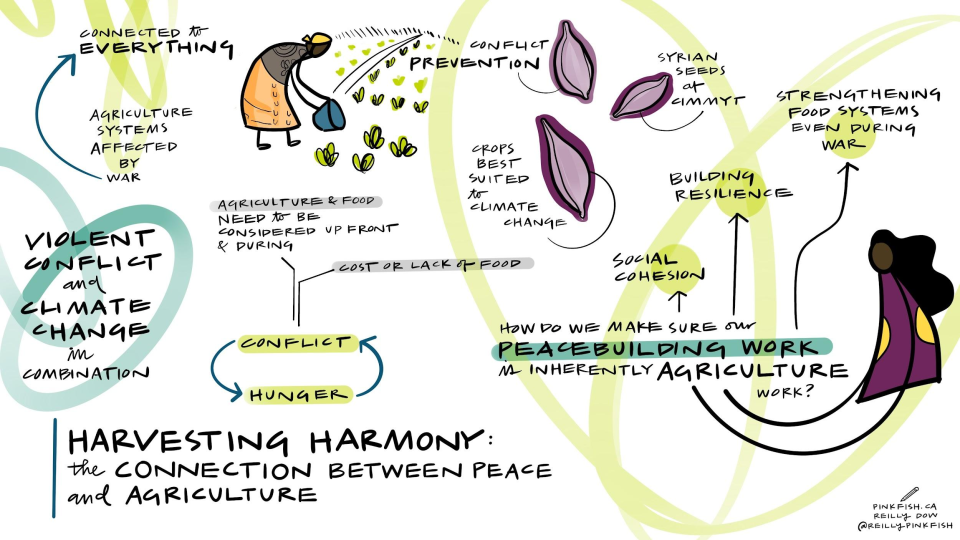

“Achieving food security by mid-century means producing at least 50 percent more food,” said U.S. Special Envoy for Global Food Security, Cary Fowler, citing a world population expected to reach 9.8 billion and suffering the dire effects of violent conflicts, rising heat, increased migration, and dramatic reductions in land and water resources and biodiversity. “Food systems need to be more sustainable, nutritious, and equitable.”

CIMMYT’s 2030 Strategy aims to build a diverse coalition of partners to lead the sustainable transformation of agrifood systems. This approach addresses factors influencing global development, plant health, food production, and the environment. At DialogueNEXT, CIMMYT and its network of partners showcased successful examples and promising directions for bolstering agricultural science and food security, focusing on poverty reduction, nutrition, and practical solutions for farmers.

Without healthy crops or soils, there is no food

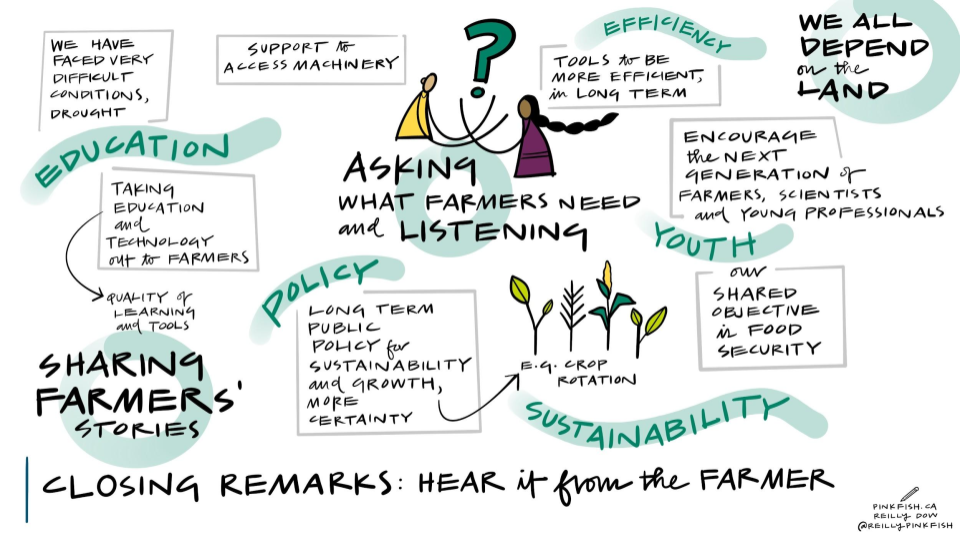

CIMMYT’s MasAgro program in Mexico has enhanced farmer resilience by introducing high-yielding crop varieties, novel agricultural practices, and income-generation activities. Mexican farmer Diodora Petra Castillo Fajas shared how CIMMYT interventions have benefitted her family. “Our ancestors taught us to burn the stover, degrading our soils. CIMMYT introduced Conservation Agriculture, which maintains the stover and traps more humidity in the soil, yielding more crops with better nutritional properties,” she explained.

CIMMYT and African partners, in conjunction with USAID’s Feed the Future, have begun applying the MasAgro [1] model in sub-Saharan Africa through the Feed the Future Accelerated Innovation Delivery Initiative (AID-I), where as much as 80 percent of cultivated soils are poor, little or no fertilizer is applied, rainfed maize is the most widespread crop, many households lack balanced diets, and erratic rainfall and high temperatures require different approaches to agriculture and food systems.

CIMMYT and African partners, in conjunction with USAID’s Feed the Future, have begun applying the MasAgro [1] model in sub-Saharan Africa through the Feed the Future Accelerated Innovation Delivery Initiative (AID-I), where as much as 80 percent of cultivated soils are poor, little or no fertilizer is applied, rainfed maize is the most widespread crop, many households lack balanced diets, and erratic rainfall and high temperatures require different approaches to agriculture and food systems.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and CIMMYT are partnering to carry out the Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS) movement in Africa and Central America. This essential movement for transforming food systems endorsed by the G7 focuses on crop improvement and soil health. VACS will invest in improving and spreading 60 indigenous “opportunity” crops—such as sorghum, millet, groundnut, pigeon pea, and yams, many of which have been grown primarily by women—to enrich soils and human diets together with the VACS Implementers’ Group, Champions, and Communities of Practice.

The MasAgro methodology has been fundamental in shaping the Feed the Future Southern Africa Accelerated Innovation Delivery Initiative (AID-I) Rapid Delivery Hub, an effort between government agencies, private, and public partners, including CGIAR. AID-I provides farmers with greater access to markets and extension services for improved seeds and crop varieties. Access to these services reduces the risk to climate and socioeconomic shocks and improves food security, economic livelihoods, and overall community resilience and prosperity.

The MasAgro methodology has been fundamental in shaping the Feed the Future Southern Africa Accelerated Innovation Delivery Initiative (AID-I) Rapid Delivery Hub, an effort between government agencies, private, and public partners, including CGIAR. AID-I provides farmers with greater access to markets and extension services for improved seeds and crop varieties. Access to these services reduces the risk to climate and socioeconomic shocks and improves food security, economic livelihoods, and overall community resilience and prosperity.

Healthy soils are critical for crop health, but crops must also contain the necessary genetic traits to withstand extreme weather, provide nourishment, and be marketable. CIMMYT holds the largest maize and wheat gene bank, supported by the Crop Trust, offering untapped genetic material to develop more resilient varieties from these main cereal grains and other indigenous crops. Through the development of hardier and more adaptable varieties, CIMMYT and its partners commit to implementing stronger delivery systems to get improved seeds for more farmers. This approach prioritizes biodiversity conservation and addresses major drivers of instability: extreme weather, poverty, and hunger.

Food systems must be inclusive to combat systemic inequities

Successful projects and movements such as MasAgro, VACS, and AID-I are transforming the agricultural landscape across the Global South. But the urgent response required to reduce inequities and the needed investment to produce more nutritious food with greater access to cutting-edge technologies demands inclusive policies and frameworks like CIMMYT’s 2030 Strategy.

“In Latin America and throughout the world, there is still a huge gap between the access of information and technology,” said Secretary of Agriculture and Livestock of Honduras, Laura Elena Suazo Torres. “Civil society and the public and private sectors cannot have a sustainable impact if they work opposite to each other.”

Ismahane Elouafi, CGIAR executive managing director, emphasized that agriculture does not face, “a lack of innovative science and technology, but we’re not connecting the dots.” CIMMYT offers a pathway to bring together a system of partners from various fields—agriculture, genetic resources, crop breeding, and social sciences, among others—to address the many interlinked issues affecting food systems, helping to bring agricultural innovations closer to farmers and various disciplines to solve world hunger.

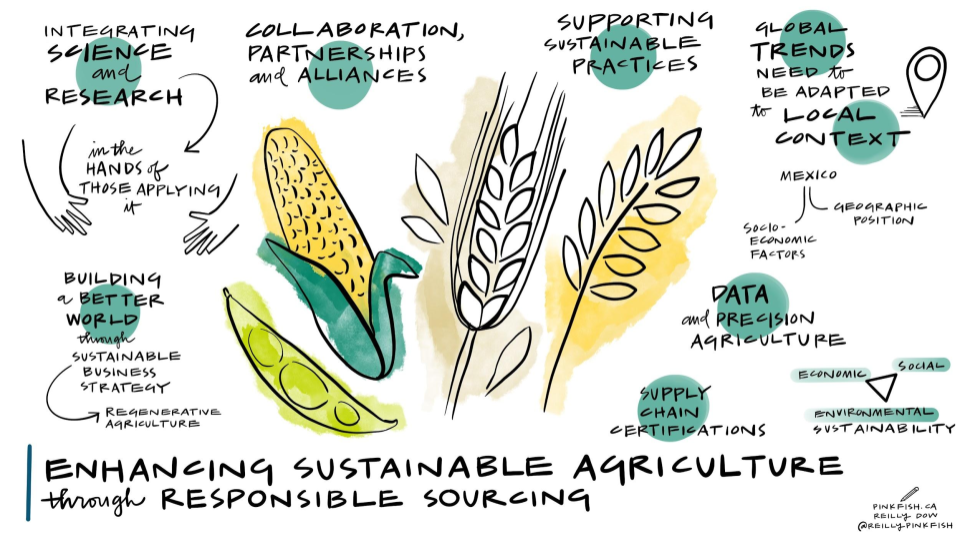

While healthy soils and crops are key to improved harvests, ensuring safe and nutritious food production is critical to alleviating hunger and inequities in food access. CIMMYT engages with private sector stakeholders such as Bimbo, GRUMA, Ingredion, Syngenta, Grupo Trimex, PepsiCo, and Heineken, to mention a few, to “link science, technology, and producers,” and ensure strong food systems, from the soils to the air and water, to transform vital cereals into safe foods to consume, like fortified bread and tortillas.

While healthy soils and crops are key to improved harvests, ensuring safe and nutritious food production is critical to alleviating hunger and inequities in food access. CIMMYT engages with private sector stakeholders such as Bimbo, GRUMA, Ingredion, Syngenta, Grupo Trimex, PepsiCo, and Heineken, to mention a few, to “link science, technology, and producers,” and ensure strong food systems, from the soils to the air and water, to transform vital cereals into safe foods to consume, like fortified bread and tortillas.

Reduced digital gaps can facilitate knowledge-sharing to scale-out improved agricultural practices like intercropping. The Rockefeller Foundation and CIMMYT have “embraced the complexity of diversity,” as mentioned by Roy Steiner, senior vice-president, through investments in intercropping, a crop system that involves growing two or more crops simultaneously and increases yields, diversifies diets, and provides economic resilience. CIMMYT has championed these systems in Mexico, containing multiple indicators of success from MasAgro.

Today, CIMMYT collaborates with CGIAR and Total LandCare to train farmers in southern and eastern Africa on the intercrop system with maize and legumes i.e., cowpea, soybean, and jack bean. CIMMYT also works with WorldVeg, a non-profit organization dedicated to vegetable research and development, to promote intercropping in vegetable farming to ensure efficient and safe production and connect vegetable farmers to markets, giving them more sources for greater financial security.

Conflict aggravates inequities and instability. CIMMYT leads the Feed the Future Sustainable Agrifood Systems Approach for Sudan (SASAS) which aims to deliver latest knowledge and technology to small scale producers to increase agricultural productivity, strengthen local and regional value chains, and enhance community resilience in war-torn countries like Sudan. CIMMYT has developed a strong partnership funded by USAID with ADRA, CIP, CRS, ICRISAT, IFDC, IFPRI, ILRI, Mercy Corps, Near East Foundation, Samaritan’s Purse, Syngenta Foundation, VSF, and WorldVeg, to devise solutions for Sudanese farmers. SASAS has already unlocked the potential of several well-suited vegetables and fruits like potatoes, okra, and tomatoes. These crops not only offer promising yields through improved seeds, but they encourage agricultural cooperatives, which promote income-generation activities, gender-inclusive practices, and greater access to diverse foods that bolster family nutrition. SASAS also champions livestock health providing food producers with additional sources of economic resilience.

National governments play a critical role in ensuring that vulnerable populations are included in global approaches to strengthen food systems. Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture, Victor Villalobos, shared examples of how government intervention and political will through people-centered policies provides greater direct investment to agriculture and reduces poverty, increasing shared prosperity and peace. “Advances must help to reduce gaps in development.” Greater access to improved agricultural practices and digital innovation maintains the field relevant for farmers and safeguards food security for society at large. Apart from Mexico, key government representatives from Bangladesh, Brazil, Honduras, India, and Vietnam reaffirmed their commitment to CIMMYT’s work.

National governments play a critical role in ensuring that vulnerable populations are included in global approaches to strengthen food systems. Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture, Victor Villalobos, shared examples of how government intervention and political will through people-centered policies provides greater direct investment to agriculture and reduces poverty, increasing shared prosperity and peace. “Advances must help to reduce gaps in development.” Greater access to improved agricultural practices and digital innovation maintains the field relevant for farmers and safeguards food security for society at large. Apart from Mexico, key government representatives from Bangladesh, Brazil, Honduras, India, and Vietnam reaffirmed their commitment to CIMMYT’s work.

Alice Ruhweza, senior director at the World Wildlife Fund for Nature, and Maria Emilia Macor, an Argentinian farmer, agreed that food systems must adopt a holistic approach. Ruhweza called it, “The great food puzzle, which means that one size does not fit all. We must integrate education and infrastructure into strengthening food systems and development.” Macor added, “The field must be strengthened to include everyone. We all contribute to producing more food.”

Generating solutions, together

In his closing address, which took place on World Population Day 2024, CIMMYT Director General Bram Govaerts thanked the World Food Prize for holding DialogueNEXT in Mexico and stressed the need for all partners to evolve, while aligning capabilities. “We have already passed several tipping points and emergency measures are needed to avert a global catastrophe,” he said. “Agrifood systems must adapt, and science has to generate solutions.”

Through its network of research centers, governments, private food producers, universities, and farmers, CIMMYT uses a multidisciplinary approach to ensure healthier crops, safe and nutritious food, and the dissemination of essential innovations for farmers. “CIMMYT cannot achieve these goals alone. We believe that successful cooperation is guided by facts and data and rooted in shared values, long-term commitment, and collective action. CIMMYT’s 2030 Strategy goes beyond transactional partnership and aims to build better partnerships through deeper and more impactful relationships. I invite you to partner with us to expand this collective effort together,” concluded Govaerts.

[1] Leveraging CIMMYT leadership, science, and partnerships and the funding and research capacity of Mexico’s Agriculture Ministry (SADER) during 2010-21, the program known as “MasAgro” helped over 300,000 participating farmers to adopt improved maize and wheat varieties and resource-conserving practices on more than 1 million hectares of farmland in 30 states of Mexico.

Visual summaries by Reilly Dow.