International coalition keeps devastating maize disease at bay, but risks still linger

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) — When maize lethal necrosis (MLN) was first reported in Bomet County, Kenya, in September 2011 and spread rapidly to several countries in eastern Africa, agricultural experts feared this emerging maize disease would severely impact regional food security. However, a strong partnership across eight countries between maize research, plant health organizations and the private seed sector has, so far, managed to contain this devastating viral disease, which can wipe out entire maize fields. As another emerging pest, the fall armyworm, is making headlines in Africa, African countries could learn a lot from the initiatives to combat MLN on how to rapidly respond to emerging crop pests and diseases.

On November 19-20, 2018, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), national research and plant protection agencies and seed companies met in Nairobi to review the third year’s progress of the MLN Diagnostics and Management Project, supported by USAID. All participants agreed that preventing any spread of the disease into southern Africa was a great success.

“The fact that we all responded rapidly and productively to this crisis serves as a testament of the success of our collective efforts,” said CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program Director, B.M. Prasanna, while addressing delegates from Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. “That no new country has reported the MLN outbreak since Ethiopia last reported it in the 2014-2015 period, and that we have managed to keep it at bay from southern Africa and west Africa is no mean feat. It would have been a major food security disaster if the disease had spread throughout sub-Saharan Africa.”

However, the MLN Community of Practice warned that risks of severe outbreaks remain, with new cases of MLN reported during the MLN 2018 survey in several parts of Uganda.

Rapid response to a food security threat

MLN is caused by the combination of the maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and other common cereal viruses mostly from the potyviridae family — a set of viruses that encompasses over 30 percent of known plant viruses — like the sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV). This viral disease can result in up to 100 percent yield loss and has devastated the incomes and food security situation of many smallholder farmers in the region.

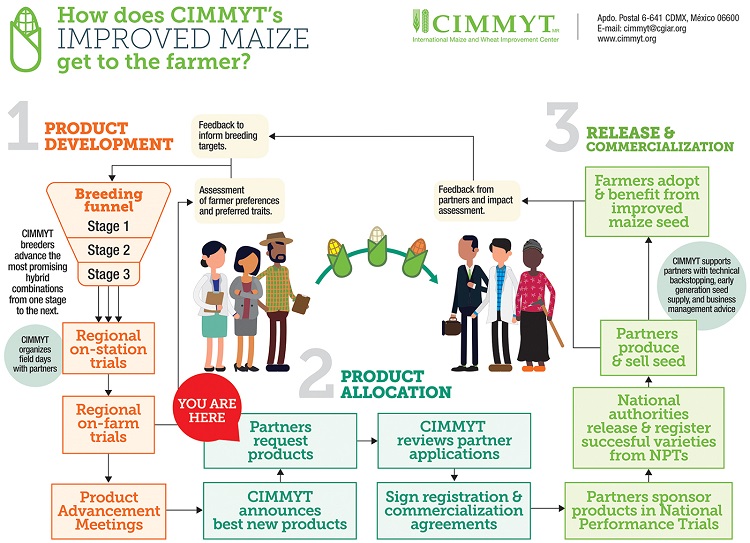

CIMMYT, in collaboration with national agricultural research institutions, national plant protection agencies and seed sector partners, developed a multi-layered response system including real-time intensive surveillance, screening, and fast-tracking of the MLN resistance breeding program. Thanks to the MLN Screening Facility in Naivasha, Kenya, maize breeders rapidly discovered that most popular maize varieties were susceptible, which could expose poor farmers to the risk of losing their entire maize crops.

Using its global collection of maize lines and numerous crop improvement innovations, CIMMYT was able to develop and release at least 15 MLN-resistant maize varieties in just 2 to 3 years.

One important step was to understand how the disease spread. Epidemiologists quickly pointed out the necessity to work with the seed companies and farmers, as the virus could be transmitted through seeds. The project helped put in place the protocols for seed firms to adhere to for their products to be MLN-free. Affordable and simple seed treatment procedures yielded promising results. The project also created awareness on better farming methods for effective disease control.

National Plant Protection Organizations were mobilized to create intensive awareness. They were also equipped and trained on low-cost innovative field diagnostic tools like MLN immunostrips and the deployment of GPS-based mobile surveillance and reporting systems.

“For the first time, Rwanda was able to conduct a comprehensive survey on MLN in farmers’ fields, commercial seed fields and at agro-dealers. We are glad that through MLN management and awareness programs within the project, MLN incidences have declined,” said Fidele Nizeyimana, maize breeder and pathologist at the Rwanda Agricultural Board (RAB) and the MLN Surveillance team lead in Rwanda.

“Equally important is that the commercial seed sector took the responsibility of testing their seed production fields, made sure that seed exchange is done in a responsible manner and implemented voluntary monitoring and surveillance within their fields,” remarked Francis Mwatuni, MLN project manager at CIMMYT.

“I am happy that Malawi has maintained its MLN-free status as per the intensive MLN surveillance activities we conducted in the country over the last three years,” noted Johnny Masangwa, senior research officer and MLN Surveillance team lead in Malawi. “We are now able to monitor both seed and grain movement through our borders for MLN traces, courtesy of the lab equipment, reagents and training on laboratory analysis we received through the project”.

B.M. Prasanna, director of the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE), discusses what the CGIAR offers in rapid response preparedness to newly emerging pests, diseases and crises.

The maize sector should remain vigilant

Daniel Bomet, maize breeder at Uganda’s National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO), warned that with new infections reported in the northern parts of his country, the maize sector needs to remain alert to the threat of MLN. “We need to step up MLN awareness and management programs, and require seed companies to follow the right procedures to produce MLN-free seeds to arrest this trend,” he said.

Tanzania Seed Association Executive Director, Bob Shuma, also warned that MLN could be spreading to the southern highlands of the country as the virus was detected in some seed shipments from three seed companies operating in that region. A comprehensive MLN survey in Tanzania will hopefully soon give an idea of the countrywide status of the disease in the country.

Conference speakers and participants noted that inefficient regulatory processes in maize seed variety release and deployment still stand in the way of rapid release of MLN resistant varieties to farmers across the region.

“How quickly we scale up and deploy the elite MLN-resistant and stress-tolerant varieties to the farmer is the next most important phase of the project,” Prasanna said.

The Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) General Manager, Phytosanitary Services, Isaac Macharia, said that with the support of the USAID Feed the Future program, the government agency has set up a team dedicated to assisting seed companies doing seed multiplication to fast-track the release of the MLN-resistant varieties to the market. Some Kenyan seed companies announced they will market MLN-resistant varieties for the next cropping season in March 2019.

As the project enters its last year, the MLN Community of Practice looks to ensure the fully functional pest surveillance and management system it has put in place is sustainable beyond the project’s life.